28 September 2021: Articles

Cytomegalovirus-Associated Nephrotic Syndrome in a Patient with Myasthenia Gravis Treated with Azathioprine: A Case Report

Mistake in diagnosis, Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Yanqiu Xu1DE, Min Chen1DE, Lin Xie1B, Xi Zhang1C, Yi Wang1F, Xiangchen Gu1AEG*DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.933380

Am J Case Rep 2021; 22:e933380

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Patients taking azathioprine (AZA) are very susceptible to development of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. The symptoms of CMV infection are varied. In some rare cases, CMV infection can even result in nephrotic syndrome.

CASE REPORT: Here, we present a rare case of nephrotic syndrome associated with CMV infection, induced by azathioprine intake. The patient, diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, was initially treated with azathioprine for 2 years. Then, the patient was admitted to the hospital due to nephrotic syndrome and acute kidney injury. Minimal change disease with acute tubular necrosis were diagnosed through biopsy. After an initial good response to hemodialysis and steroids, the patient developed severe pneumonia and oral ulcers. Further anti-CMV IHC staining of kidney tissues showed positive cells in tubules, indicating nephrotic syndrome secondary to CMV infection.

CONCLUSIONS: This case reminded us that CMV may be an under-recognized cause of nephrotic syndrome. Patients treated with azathioprine are very susceptible to developing CMV infection. During the diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome, we should always take CMV infection into consideration, especially in patients with on azathioprine.

Keywords: Acute Kidney Injury, azathioprine, case reports, Glycoprotein H, Cytomegalovirus, nephrotic syndrome, Humans, Myasthenia Gravis

Background

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the herpesvirus family. It usually causes subclinical diseases with asymptomatic syndromes or mild infection with spontaneous cure in immunocompetent adults [1]. However, it can cause severe infections in AIDS patients, solid-organ transplant patients, and hematopoietic stem-cell transplant recipients, resulting in uncontrolled viral replication [2]. CMV infection may also occur in other immune-compromised patients, mostly patients on immunosuppressive treatment. The symptoms can be varied, including fever, diarrhea, pneumonia, hepatitis, and encephalitis. A systematic meta-analysis of case reports and reviews found that severe CMV infection most common involve the gastrointestinal tract, followed by the central nervous system, and then hematological abnormalities [3]. In some rare cases, azathioprine leads to immunosuppression and is associated with CMV infection. Here, we present a case report of a patient with secondary nephrotic syndrome and acute tubular necrosis due to CMV infection, subsequent to azathioprine treatment.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital because of a 1-week history of edema and oliguria. Two years before admission, she was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis and was subsequently taking azathioprine 100 mg/day. She has also been diagnosed with breast cancer 10 years ago and had a mastectomy. Other medical history included hypertension for 10 years.

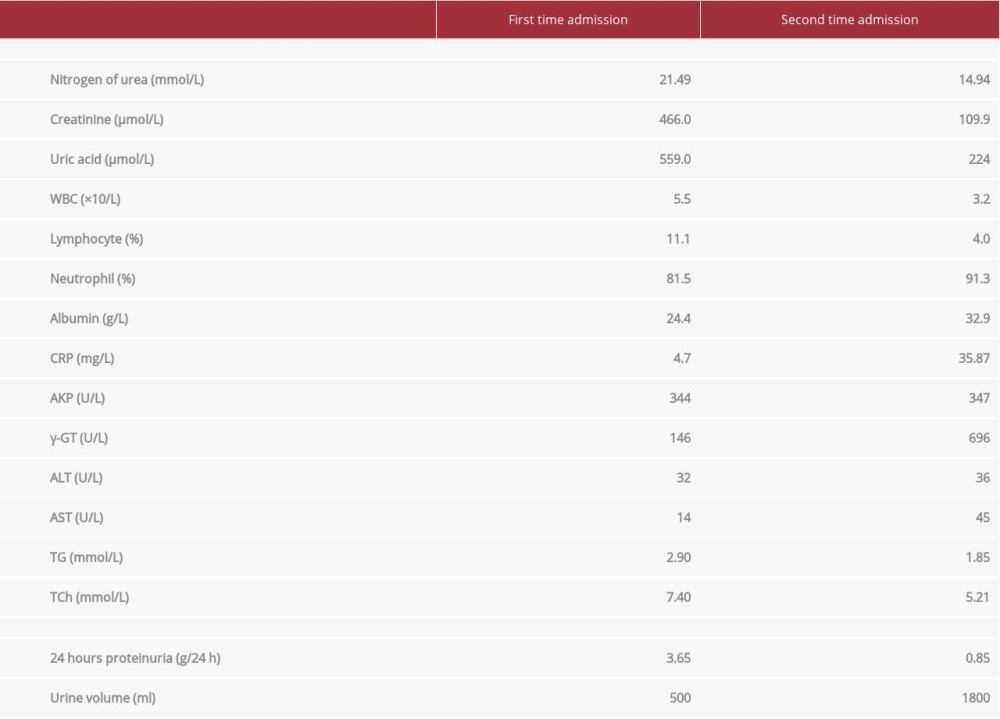

Laboratory test results are shown in Table 1. Hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, proteinuria, and edema met the diagnostic criteria for nephrotic syndrome. Furthermore, the elevated serum creatinine met criteria for AKI diagnosis. Light microscopy and immunofluorescence of kidney biopsies suggested minor glomerular abnormalities and acute tubular necrosis. Electronic microscopy indicated extensive foot process effacement of podocytes (Figure 1). After ruling out the possible secondary causes, the patient received hemodialysis and also started intravenous administration of methylprednisolone 40 mg per day. After edema was alleviated and serum creatinine levels returned to normal, the patient was treated with prednisone at an initial dose of 1 mg/kg per day orally and discharged home.

However, 2 weeks later, the patient was re-admitted for fever, dyspnea, and large oral ulcers (Figure 2). Laboratory test results are shown in Table 1. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed viral pneumonia (Figure 3). We suspected the patient had viral infections. A further viral work-up came back negative for Epstein-Barr virus, Coxsackie virus, and rubella virus antibodies. However, CMV-IgG and IgM antibodies were positive (CMV-IgG 500.00 IU/mL, range 0.00–1.0 IU/mL; CMVIgM 5.25 IU/mL, range 0.00–0.70 IU/mL). The serum CMV PCR test result was also positive (CMV viral load 5236 copies/mL).

To identify whether a patient was infected with CMV before or after the initiation of prednisone, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining is regarded as the criterion standard of CMV diagnosis [4,5], so we performed anti-CMV lHC staining on the patient’s renal tissue (CMV 8B1.2, 1G5.2, and 2D4.2, Cell Marque, USA). The IHC staining of renal tissues showed positive staining of cells in tubules compared to the negative control (Figure 4). These results strongly confirmed our suspicion that the patient was initially infected with cytomegalovirus only after initiation of azathioprine treatment. The nephrotic syndrome was secondary to CMV infection.

Given the probable causal relationship between the patient’s medications and the development of CMV pneumonia, azathioprine was discontinued, and prednisone was quickly reduced to 10 mg/day. Induction therapy with ganciclovir was administered intravenously at a dose of 5 mg/kg twice a day.

However, after 1 week of treatment, the patient required intubation and was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Her condition was complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome and bacterial pneumonia, and she died of respiratory failure after transfer to the ICU.

Discussion

Cytomegalovirus is a unique virus, and primary exposure to CMV can occur at an early age. It is rare for immunocompe-tent individuals to manifest signs of CMV infections. Adult-onset infection mainly occurs due to primary infection, rein-fection, or activation of a latent infection. Azathioprine is a prodrug converted in the liver to 6-mercaptopurine, and, via further metabolic steps, is converted to the biologically active metabolite 6-thioguanine nucleotide (6-TGN) [6]. Purine synthesis is inhibited, and the proliferation of T and B lymphocytes are prevented as well [7]. As a result, immunosuppression is induced by azathioprine. Thus, patients with long-term azathioprine intake are more susceptible to developing CMV infections in the late stage.

It has been widely reported that patients with inflammatory bowel disease who are receiving azathioprine treatment are susceptible to CMV infection [8–11]. A systemic review of CMV pneumonia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease found that thiopurines carry a disproportionately higher risk of viral infection reactivation, particularly CMV [12].

Furthermore, CMV infection can present in various ways. Besides CMV pneumonitis, several case reports showed that immunosuppressive therapy might have a role in development of CMV retinitis [13,14], as well as thrombocytopenia [15], myalgia [16], arthralgia [17,18], hepatitis [19], pericarditis [20], or gastrointestinal [8,10] and neurological disorders [19,21], and even oral ulcers [22,23]. In some rare cases, CMV infection also presents as nephrotic syndrome. It was reported [24] that a 5-month-old infant in whom genetic mutations were ruled out presented with nephrotic syndrome and was diagnosed with CMV infection. Antiviral treatment leads to a complete remission of the nephrotic syndrome. Moreover, CMV infection can cause FSGS, especially collapsing FSGS, both in immune-competent patients [25–27] and in renal transplant recipients [28–30]. A prevalence of 1.2% for CMV nephritis in kidney transplant patients was also reported, mainly characterized by tubule-interstitial nephritis [31]. In the diagnosis of the present patient, we could not rule out the possibilities of FSGS, owing to low numbers of glomeruli in the biopsy (only 5 glomeruli were counted in the renal tissue). This may also explain why we did not observe anti-CMV-positive staining in the 5 glomeruli in the renal tissue.

Regarding this patient’s treatment, without considering CMV infection-induced nephrotic syndrome at the beginning, we directly added steroids to azathioprine, which further suppressed the immune system and exacerbated the CMV infection. Thus, in the late stage of the disease, the patient manifested CMV pneumonia and oral ulcers. We withdrew immune-suppression drugs immediately and initiated intravenous ganciclovir treatment. However, the patient’s condition deteriorated, and she eventually died of respiratory failure. Although intravenous ganciclovir has long been regarded as the criterion standard for treating severe CMV infection, the antiviral treatment in our patient seemed to be ineffective. Studies have demonstrated that mutations in CMV UL97, which encode viral kinase, are associated with ganciclovir resistance [32]. Mutations in UL54, which encodes for CMV DNA polymerase, confer resistance (or cross-resistance) to ganciclovir, cidofovir, and/or foscarnet [33]. New drugs and vaccines are being developed to treat mutated CMV.

From a clinical perspective, it is essential to keep in mind that, in some instances, apparently nephrotic syndrome represents a lesion arising secondary to an extraglomerular disease process. Thus, patients should be thoroughly evaluated for potential underlying diseases, particularly neoplasia and drug exposure, when atypical features are present (such as weight loss, anorexia, lymphadenopathy, or acute renal failure) [34]. Routine screening of CMV serology before initiating treatment should be highly recommended for patients with nephrotic syndrome, especially those receiving azathioprine treatment.

Conclusions

This case report should serve as a reminder of a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that can occur in patients who receive immunosuppressive treatment, especially thiopurines. Early diagnosis is crucial owing to the condition’s high mortality rate, and the failure to appropriately diagnose and treat these patients promptly can lead to significant morbidity and mortality.

Figures

References:

1.. Chen SJ, Wang SC, Chen YC, Antiviral agents as therapeutic strategies against cytomegalovirus infections: Viruses, 2019; 12(1); 21

2.. Dioverti MV, Razonable RR, Cytomegalovirus: Microbiol Spectr, 2016; 4(4); DMIH2-0022-2015

3.. Osawa R, Singh N, Cytomegalovirus infection in critically ill patients: A systematic review: Crit Care, 2009; 13(3); R68

4.. Mills AM, Guo FP, Copland AP, A comparison of CMV detection in gastrointestinal mucosal biopsies using immunohistochemistry and PCR performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue: Am J Surg Pathol, 2013; 37(7); 995-1000

5.. Liao X, Reed SL, Lin GY, Immunostaining detection of cytomegalovirus in gastrointestinal biopsies: clinicopathological correlation at a large academic health system: Gastroenterology Res, 2016; 9(6); 92-98

6.. Hisamuddin IM, Wehbi MA, Yang VW, Pharmacogenetics and diseases of the colon: Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 2007; 23(1); 60-66

7.. Quemeneur L, Gerland LM, Flacher M, Differential control of cell cycle, proliferation, and survival of primary T lymphocytes by purine and pyrimidine nucleotides: J Immunol, 2003; 170(10); 4986-95

8.. Stack R, Parihar V, Ryan B, Alakkari A, CMV pneumonitis in an immunosup-pressed Crohn’s disease patient: QJM, 2016; 109(8); 553-54

9.. Vakkalagadda CV, Cadena-Semanate R, Non LR, Cytomegalovirus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in a 59-year-old woman with ulcerative colitis: Am J Med, 2017; 130(7); e305-e6

10.. Preda CM, Sandra I, Becheanu G, Endoscopic aspect of a severe CMV colitis induced by azathioprine in a patient with ulcerative colitis: J Gastrointestin Liver Dis, 2016; 25(4); 429

11.. Rowan C, Judge C, Cannon MD, Severe symptomatic primary CMV infection in inflammatory bowel disease patients with low population sero-prevalence: Gastroenterol Res Pract, 2018; 2018; 1029401

12.. Ozaki T, Yamashita H, Kaneko S, Cytomegalovirus disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients with rheumatic diseases: A case series and literature review: Clin Rheumatol, 2013; 32(11); 1683-90

13.. Ammari W, Berriche O, [CMV retinitis in a patient with ulcerative colitis taking azathioprine.]: Pan Afr Med J, 2015; 21; 227 [in French]

14.. Shahnaz S, Choksi MT, Tan IJ, Bilateral cytomegalovirus retinitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and end-stage renal disease: Mayo Clin Proc, 2003; 78(11); 1412-15

15.. Koukoulaki M, Ifanti G, Grispou E, Fulminant pancytopenia due to cytomegalovirus infection in an immunocompetent adult: Braz J Infect Dis, 2010; 14(2); 180-82

16.. Yaari S, Koslowsky B, Wolf D, Chajek-Shaul T, Hershcovici T, CMV-related thrombocytopenia treated with foscarnet: A case series and review of the literature: Platelets, 2010; 21(6); 490-95

17.. Gong J, Meyerowitz EA, Isidro RA, Kaye KM, Primary cytomegalovirus infection with invasive disease in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease: BMJ Case Rep, 2019; 12(9); e230056

18.. Jia J, Shi H, Liu M, Cytomegalovirus infection may trigger adult-onset still’s disease onset or relapses: Front Immunol, 2019; 10; 898

19.. Tezer H, Kanik Yuksek S, Gulhan B, Cytomegalovirus hepatitis in 49 pediatric patients with normal immunity: Turk J Med Sci, 2016; 46(6); 1629-33

20.. Wu CT, Huang JL, Pericarditis with massive pericardial effusion in a cytomegalovirus-infected infant: Acta Cardiol, 2009; 64(5); 669-71

21.. Zhang XY, Fang F, Congenital human cytomegalovirus infection and neurologic diseases in newborns: Chin Med J (Engl), 2019; 132(17); 2109-18

22.. Sato S, Takahashi M, Takahashi T, A Case of cytomegalovirus-induced oral ulcer in an older adult patient with nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy: Case Rep Dent, 2020; 2020; 8843816

23.. Schubert MM, Epstein JB, Lloid ME, Cooney E, Oral infections due to cytomegalovirus in immunocompromised patients: J Oral Pathol Med, 1993; 22(6); 268-73

24.. Hogan J, Fila M, Baudouin V, Cytomegalovirus infection can mimic genetic nephrotic syndrome: A case report: BMC Nephrol, 2015; 16; 156

25.. Presne C, Cordonnier C, Makdassi R, [Collapsing glomerulopathy and cytomegalovirus, what are the links?]: Presse Med, 2000; 29(33); 1815-17 [in French]

26.. Tomlinson L, Boriskin Y, McPhee I, Acute cytomegalovirus infection complicated by collapsing glomerulopathy: Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2003; 18(1); 187-89

27.. Grover V, Gaiki MR, DeVita MV, Schwimmer JA, Cytomegalovirus-induced collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: Clin Kidney J, 2013; 6(1); 71-73

28.. Patel AM, Zenenberg RD, Goldberg RJ, De novo CMV-associated collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in a kidney transplant recipient: Transpl Infect Dis, 2018; 20(3); e12884

29.. Wynd E, Stewart A, Burke J, Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis associated with acute cytomegalovirus infection in a renal transplant: Pediatr Transplant, 2019; 23(6); e13538

30.. Greze C, Garrouste C, Kemeny JL, [Collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis induced by cytomegalovirus: A case report]: Nephrol Ther, 2018; 14(1); 50-53 [in French]

31.. Agrawal V, Gupta RK, Jain M, Polyomavirus nephropathy and Cytomegalovirus nephritis in renal allograft recipients: Indian J Pathol Microbiol, 2010; 53(4); 672-75

32.. Coppock GM, Blumberg E, New treatments for cytomegalovirus in transplant patients: Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens, 2019; 28(6); 587-92

33.. Razonable RR, Drug-resistant cytomegalovirus: Clinical implications of specific mutations: Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2018; 23(4); 388-94

34.. Glassock RJ., Secondary minimal change disease: Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2003; 18(Suppl .6); vi52-58

Figures

In Press

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250