05 February 2022: Articles

Severe Postoperative Bleeding Following Minor-to-Moderate Abdominal and Flank Liposuction Performed at a Day Surgery Center: A Case Report

Unusual clinical course, Challenging differential diagnosis, Diagnostic / therapeutic accidents, Management of emergency care, Clinical situation which can not be reproduced for ethical reasons

Ori Berger1ABCDEF*, Evgenia Cherniavsky2DEF, Ran Talisman1ABCDEFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.934049

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e934049

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Liposuction is a one of the most common aesthetic procedures. The super-wet and tumescent techniques are used most frequently. Both serve to reduce collateral blood loss, facilitate the suctioning procedure, and providing local anesthesia. Overall, liposuction is considered safe and effective, with minor adverse effects such as swelling, minute bleeding, contour irregularities, and seroma. Serious complication such as life-threatening bleeding are rare. In this case report, we present a patient with significant postoperative bleeding following minor-to-moderate liposuction performed at a day surgery center.

CASE REPORT: A 51-year-old healthy man, 4 days after 1600-cc aspirate tumescent liposuction performed in a day surgery center, was admitted to our ward with tachycardia, weakness, abdominal pain and disseminated hematoma. On admission, laboratory testing showed hematocrit of 20.9% and hemoglobin of 6.9 gr/dl. Immediate abdominal CT angiography was performed to exclude active bleeding, showing diffused hematoma in the subcutaneous fat all over the abdomen and scrotum, with some edema without active bleeding. The patient was treated with blood transfusion to facilitate fast home discharge during the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic that time.

CONCLUSIONS: We discuss the common work-up and treatment of postoperative hemorrhage. Blood transfusion following minor-to-moderate liposuction is unusual but during the COVID-19 pandemic it can facilitate quick discharge of a patient with postoperative hemorrhage with no active bleeding. Improper patient selection, an inexperienced surgeon, and inadequate operating locale can all result in postoperative complications. We call for the formulation of more detailed guidelines for liposuction setting.

Keywords: Ambulatory Surgical Procedures, Esthetics, Hemorrhage, Lipectomy, Postoperative Complications, Surgery, Plastic, Abdomen, COVID-19, Humans, Male, Pandemics, Postoperative Hemorrhage, SARS-CoV-2

Background

Liposuction is one of the most commonly performed aesthetic surgical procedures worldwide [1,2]. The procedure is considered powerful and effective and is used for body contouring and as a treatment in a variety of other surgical diagnoses such as breast reconstruction, gynecomastia, and lipedema. Liposuction emerged in the 1970s and kept expanding ever since [3–7]. The procedure involves injecting infiltrate solutions into the fat tissue and suctioning the content through cannulas. There are 4 main techniques: dry, wet, super-wet, and tumescent, all based on the ratio of the amount of fluid infiltrated to the aspirate procured [3,4]. Both the super-wet and the tumescent techniques are popular among physicians due to the reduced collateral blood loss, good local anesthesia capabilities, and reduced post-liposuction skin irregularities due to the use of smaller cannulas [3,4,6,7]. The infiltrate usually contains lidocaine and epinephrine added to normal saline, while some practitioners add tranexamic acid to reduce the inevitable blood loss during the procedure [3,4,6]. Over time, a variety of technical advances have been added to the traditional method, including ultrasound, power, waterjet, laser, and radiofrequency. Each technology has its own unique set of benefits and complications. Currently, none of them have any significant superiority over the others [4,5,8].

Cosmetic procedures in general and liposuction specifically have gained popularity and are perceived by the public as minor procedures [9–11]. Liposuction is presented as being safe, relatively harmless, and quick [5,9,11]. Coupled with a lack of restrictive laws, it has become a procedure done by non-plastic surgeons and non-physicians [9]. The procedure is performed at a doctor’s office, in an ambulatory day surgery center, or in a hospital [4,7].

Minor adverse effects of the procedure are relatively rare and include seroma, swelling, contour irregularities, skin hyper-pigmentation, and local skin necrosis [3,4,6]. A large volume (over 5 L) of aspirate during liposuction increases the risk of significant bleeding, pulmonary emboly, fat embolisms, sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, and perforation of internal organs and death [3–7]. Bleeding, formerly the most common cause of death due to lipo-aspiration, now represents just 4.6% of lethal events [3]. The rate of serious postoperative complications has been dramatically reduced by growing worldwide experience performing the procedure and better perioperative monitoring [3,4].

The present clinical report presents a patient who was admitted to the plastic surgery ward 4 days after a minor-to-moderate liposuction procedure, during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, with hemodynamic instability. We discuss in brief the possible clinical sequela that led to the patient’s condition and the selected treatment and present our thoughts regarding implementation of liposuction in ambulatory surgery settings.

Case Report

A 51-year-old man was admitted to the Emergency Department due to weakness, dizziness, palpitations, and abdominal and scrotal pain accompanied by significant edema 4 days after undergoing an abdominal liposuction procedure. The patient had no significant medical history, denied any anticoagulant treatment, and reported smoking cessation 3 weeks prior to his surgery. The patient underwent a tumescent liposuction from the abdomen and flanks under general anesthesia in a day surgery center equipped with all necessary gear and monitoring, by a board-certified plastic surgeon. The infiltration solution consisted of 2.5 L ringer lactate, each liter containing 400 mg of lidocaine; 1: 1 000 000 adrenaline, and 50 ml 8.4% bicarbonate sodium. Following infiltration of the tumescent solution by electric pump, a Micro-Air™ device was used to perform the liposuction with a 4-mm accelerator III cannula. Six access points were used: right and left flanks, right and left lower abdomen, suprapubic, and umbilical. The aspirate container showed 1600 cc of aspirate with 100 cc blood. The patient was discharged home after an uneventful 2-h postsurgery observation, without any special concerns.

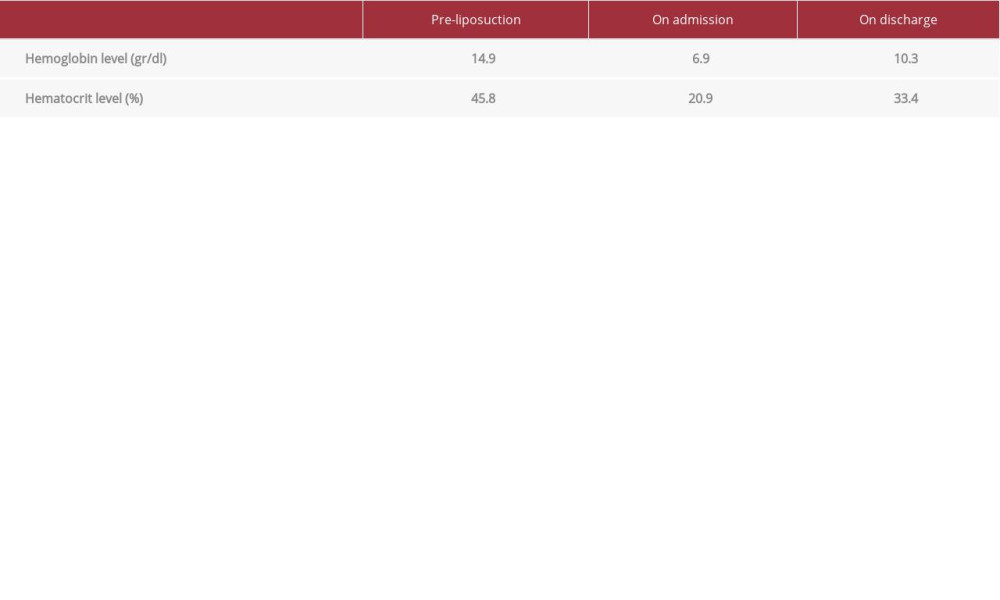

On admission to our Emergency Department, a physical examination revealed a diffused abdominal and scrotal hematoma, and 6 surgical wounds with no signs of inflammation (Figure 1). The patient’s height was 173 cm, he weighed 87.5 kg, and his body mass index (BMI) was 29. Vital signs showed a heart rate of 91, and blood pressure of 148/89. Lab work showed hematocrit of 20.9% (base of 45.8%) and hemoglobin of 6.9 gr/dl (base of 14.9 gr/dl), with INR 0.9 and platelet count 172 K/uL. To rule out the possibility of active bleeding and a possible need for angiographic vessel occlusion, an immediate abdominal CT angiography scan was performed. The imaging displayed diffused edema with signs of hematoma of the subcutaneous fat in the above-noted regions, with no active bleeding (Figure 2).

The patient was admitted to the plastic surgery ward for close observation. However, the patient insisted on leaving the hospital as soon as possible due to the COVID-19 pandemic at the time. Therefore, to facilitate a quick discharge, the patient received a transfusion of 2 units of packed red blood cells. Following the transfusion, the patient stated he no longer had palpitations, his heart rate dropped to 74, hematocrit level rose to 33.4%, and hemoglobin climbed to 10.3 g/dl (Table 1), enabling the discharge of the patient uneventfully. Six-week follow-up revealed he was feeling well and returned to his regular daily activities without any restrictions.

Discussion

We report the case of a healthy man with an abnormal amount of post-liposuction hemorrhage. Blood loss in liposuction can occur in 1 of 2 ways: external and internal [12]. External blood loss can be subdivided to 2 types: (1) Measurable, in the aspirate collecting container, and (2) unmeasurable, in drapes, sponges, and dressing. Internal blood loss is the blood that exsanguinates out of blood vessels to the surrounding tissue, or the “third space” [4,12]. The mechanism of blood loss is mainly via disruption of capillaries and small blood vessels [11]. Our patient’s clinical symptoms and CT angiography scan (Figure 2) excluded continuous bleeding through a torn unconcluded blood vessel [13] and suggested 3 differential diagnoses.

The first possible diagnosis was that the intraoperative blood loss of 100 cc was an underestimation of the patient’s blood loss during and immediately after the procedure. The blood loss caused a hemoglobin decrease of 8 gr/dl, which correlates roughly to 2.5 liters of blood. If all the hemorrhage occurred during the procedure it would have caused class IV hemorrhagic shock, which should have influenced the patient’s clinical condition and alerted the surgical team [14]. Since the patient was uneventfully discharged after a short observation time, we assumed the blood loss occurred over a longer period.

The second possible diagnosis was of coagulopathy, including disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) secondary to a combination of hemodilution, hypothermia, and liposuction trauma [11]. Although hypothermia and hemodilution have been observed before during tumescent liposuction [15], none of the patient`s blood work, performed on admission, supported such an explanation.

The third possible diagnosis was that the blood loss slowly accumulated in the tissues after the vasoconstricting effect of the adrenaline in the tissue subsided, until natural hemostasis occurred. This might have been following the subcision of the minor vessels [14,15]. The body of a man can contain 3 liters of blood, with minimal inconvenience and no serious pains, in his subcutaneous tissue around the abdomen, flanks, back, and groin. Our patient’s CT scan showed diffuse edema intermingled with hematoma around the noted regions (Figure 2) [14]. The patient’s time of presentation to the Emergency Department also supports such a diagnosis.

In our case, the patient was referred to the hospital during a peak in the COVID-19 pandemic in a hemodynamic marginal status with 6.9 gr/dl hemoglobin and no clear-cut indication for urgent blood transfusion [13,16]. However, the patient expressed his desire to have the quickest possible treatment because he wanted to return to his daily routine as soon as possible and his distress over the possibility of contracting COVID-19 while in the hospital. Thus, even though close observation was the treatment of choice in normal circumstances, an unorthodox treatment with blood transfusion was chosen, which led to a faster recovery and a quicker discharge from hospitalization.

After more than 50 years of experience using liposuction, this cosmetic procedure, once performed only by trained and experienced surgeons, is now safe, easy to perform, has good results and noticeable contour improvement, and allows for a fast return to daily patient routine [3,4,6]. The procedure can be conducted in the doctor’s office, an ambulatory day surgery center, or in a hospital. Two main considerations influencing the choice of the setting for the surgical procedure are proper patient selection and economic feasibility.

Proper patient selection is the ability to discern which patients will need to be operated on in a hospital setting. In selected patients this concern is not subject to interpretation. For instance, the Ministry of Health of Israel guidelines forbids liposuction with an aspirate of more than 5 liters, or patient undergoing liposuction with BMI that exceeds 35 to be performed in settings other than a hospital [17]. Current guidelines forbid office-based liposuction in patients who will require an overnight stay [6], but aside from certain high-risk patients, the guidelines call for surgeons to decide which patients will need an overnight stay according to their professional judgment [6]. Several factors must be considered when selecting the proper setting regarding postoperative hemorrhage risk: the ambient fibrous tissue and blood vessel distribution in the intended area for suctioning [18]. Our patient, who had 2.5-liter liposuction aspirate removed from the abdomen and flanks, was at relatively greater risk of postoperative bleeding, as those areas have a higher likelihood of blood vessel injury due to higher vascular density and containing more fibrous tissue, which necessitates the application of greater force, thus increasing the risk for collateral vascular harm [18]. Indeed, as noted above, the patient had late bleeding, probably after the vasoconstrictive effect of the adrenaline wore off. The medical complexity of patients and procedures performed in the office setting are increasing [19]. Complex cases, and lack of well-defined regulations, accentuate the advantage of a surgeon who is a board-certified plastic surgeon vs less experienced and educated practitioners.

Economic feasibility refers to lowering the procedure’s cost, thus increasing its availability to a wider population. This consists of 2 main elements: reducing the surgeon’s fee, or reducing the operation room cost. Understandably, most surgeons will prefer to reduce the operating room cost and therefore perform the procedure in a more economic setting such as an office or at an ambulatory surgery center, which is often suitable for the patient’s and surgeon’s needs [4]. Past studies have demonstrated that any financial savings when performing surgery in the outpatient setting is quickly lost if safety is compromised and complications are encountered [7]. Our patient’s procedure could have been performed in a day surgery center, but both the patient and surgeon would have benefited from the hospital setting’s advantage of longer postsurgical monitoring despite the initial added costs.

We described the case of a major complication following minor abdominal liposuction, the most common anatomical area for litigation after liposuction [5]. Being a case report, it is not possible to form any generalizations or causative associations. The potential for imprecisions and bias regarding reported postsurgical complications is within the bounds of possibility, due to the sensitive nature of such accounts. We conclude that this case report, and others which describe adverse effects and complications [9,20], help form a more balanced and whole picture regarding the safety of liposuction. It shows the need for careful patient selection, and the importance of an experienced surgeon, well-functioning surgical team, and adequate follow-up care when performing an office-based procedure. We believe more detailed and clearer guidelines will help surgeons to choose the correct setting for liposuction and reduce the incidence of major complications.

Conclusions

We described the case of a male patient with a major hemorrhage following minor abdominal liposuction.

Referring the treatment of post-liposuction hemorrhage, in the healthy stable patient with no signs of active bleeding, we support the common work-up and management and a joint patient-surgeon decision on the course of treatment. Although the patient could have benefited from watchful observation, in the unusual situation of the COVID-19 pandemic, blood trans-fusion resuscitation can be considered as a way to get the patient back home promptly.

The challenge of choosing the most suitable setting for lipo-suction involves proper patient selection and economic feasibility with adequate patient care. In complex cases, and the unusual circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, the involvement of an experienced board-certified plastic surgeon can help assure the safety of high-risk patients, and the financial value of an outpatient setting. This study aimed to help form a more balanced approach to choice of setting of liposuction, but it is not in its scope to recommend any guidelines. We call for further research and formulation of unequivocal, clear, and more detailed guidelines on the subject of liposuction setting.

Figures

References:

1.. : ISAPS International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2019, 2019, USA Available at: https://www.isaps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Global-Survey-2019.pdf

2.. : Plastic Surgery Statistics Report 2020, 2020, USA Available at:https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/Statistics/News/2020/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2020.pdf

3.. Bellini E, Grieco MP, Raposio E, A journey through liposuction and liposculpture: Review: Ann Med Surg (Lond), 2017; 24; 53-60

4.. Chia CT, Neinstein RM, Theodorou SJ, Evidence-based medicine: liposuction: Plast Reconstr Surg, 2017; 139(1); 267e-74e

5.. Elhawary H, Ammar , Aldien S: When liposuction goes wrong: An analysis of medical litigation, 2021 Available at: https://academic.oup.com/asj/advance-article/doi/10.1093/asj/sjab156/6199857

6.. Mendez BM, Coleman JE, Kenkel JM, Optimizing patient outcomes and safety with liposuction: Aesthet Surg J, 2019; 39(1); 66-82

7.. Kaoutzanis C, Gupta V, Winocour J, Cosmetic liposuction: Preoperative risk factors, major complication rates, and safety of combined procedures: Aesthet Surg J, 2017; 37(6); 680-94

8.. Shridharani SM, Broyles JM, Matarasso A, Liposuction devices: Technology update: Med Devices (Auckl), 2014; 7(1); 241-51

9.. Ezzeddine H, Husari A, Nassar H, Life-threatening complications post-liposuction: Aesthetic Plast Surg, 2018; 42(2); 384-87

10.. Lehnhardt M, Homann HH, Daigeler A, Major and lethal complications of liposuction: A review of 72 cases in Germany between 1998 and 2002: Plast Reconstr Surg, 2008; 121(6); 396e-403e

11.. Montrief T, Bornstein K, Ramzy M, Plastic surgery complications: A review for emergency clinicians: West J Emerg Med, 2020; 21(6); 179-89

12.. Dixit VV, , Wagh MS. Unfavourable outcomes of liposuction and their management: Indian J Plast Surg, 2013; 46(2); 377-92

13.. Shiffman MA, Prevention and treatment of liposuction complications: Liposuction principles and practice, 2016; 777-88, Berlin, Springer

14.. You JS, Chung YE, Baek SE, Imaging findings of liposuction with an emphasis on postsurgical complications: Korean J Radiol, 2015; 16(6); 1197-206

15.. Bennett GD, Anesthesia for liposuction: Liposuction principles and practice, 2016; 3-49, Berlin, Springer

16.. Goodnough LT, Levy JH, Murphy MF, Concepts of blood transfusion in adults: Lancet, 2013; 381(9880); 1845-54

17.. : Rules for performing surgeries and anesthesia in community surgical clinics, 2012, Israel

18.. Shiffman MA, Principles of liposuction: Liposuction principles and practice, 2016; 145-47, Berlin, Springer

19.. Dadwood SS, Green MS, Anesthesia for office based cosmetic procedures: Anesthesiology: A Practical Approach, 2018; 265-71, Springer

20.. Mrad S, El Tawil C, Sukaiti WA, Chebl , Cardiac arrest following liposuction: A case report of lidocaine toxicity: Oman Med J, 2019; 34(4); 341-44

Figures

In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942937

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943275

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943411

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250