20 December 2020: Articles

A Case of Malaria Treated with Artesunate in a 55-Year-Old Woman on Return to Florida from a Visit to Ghana

Management of emergency care

Jose A. Rodriguez1ADE*, Alejandra A. Roa1BE, Ana-Alicia Leonso-Bravo1BE, Pratik Khatiwada1BF, Paula Eckardt2G, Juan Lemos-Ramirez3DEDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.926097

Am J Case Rep 2020; 21:e926097

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Malaria is the infection caused by inoculation with the mostly obligate intraerythrocytic protozoa of the genus Plasmodium. Severe malaria manifests as multiple organ dysfunction with high parasitemia counts characterized by coma, stupor, and severe metabolic acidosis. Physicians in the United States do not frequently encounter patients with malaria, and the drugs are only available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which makes the management of this disease somewhat complicated. In 2019, the marketing of quinine for malaria was discontinued. In May 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of intravenous artesunate for the treatment of adults and children with severe malaria. This case report describes a case of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in a 55-year-old woman who returned home to Florida from a visit to Ghana.

CASE REPORT: A previously healthy 55-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presented to the Emergency Department (ED) of a hospital in south Florida due to cyclic fever for 7 days. The patient’s family reported mental status changes since symptom onset. The patient had returned from a 10-day trip to Ghana 18 days prior to admission. On arrival to the ED, the patient appeared lethargic and within hours was in respiratory distress. She was intubated and mechanically ventilated in the ED for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. A malaria smear was positive with 25% parasitemia, and a diagnosis of severe malaria was made, consistent with P. falciparum infection complicated by multi-organ failure. Infectious disease consultation was obtained and an infusion of intravenous (IV) quinidine and IV doxycycline was emergently started due to the anticipated delay in obtaining artesunate. During the second day of admission, the patient had QTc prolongation, so quinidine was switched to IV artesunate. The parasitemia and acidosis started improving by the third day of therapy.

CONCLUSIONS: Given that artesunate is more effective, easier to dose, and more tolerable than quinidine, it is now the treatment of choice for severe malaria in the United States.

Keywords: Antimalarials, Critical Care, Malaria, Protozoan Infections, Plasmodium falciparum, Artesunate, Child, Florida, Ghana, Malaria, Falciparum, United States

Background

Malaria is the infection caused by the mostly obligate intraerythrocytic protozoa of the genus

Malaria occurs primarily in tropical and some subtropical regions of Africa, Central and South America, Asia, and Oceania, with an estimated 228 million cases worldwide in 2018 (93% of them occurring in Africa) [2]. About 2000 cases of malaria are diagnosed in the United States each year. Almost all these cases are imported by returning travelers or immigrants from endemic regions, with a limited number possibly occurring through local mosquito-borne transmission [2]. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported that among the 2000 cases of malaria diagnosed in the United States each year, about 300 cases are severe. The majority of these severe cases involve travelers returning from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [3].

In 2019, the marketing of quinine for malaria was discontinued in the United States. In May 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of intravenous artesunate for the treatment of severe malaria, with the recommendation that it should be followed by a full course of oral antimalarial treatments [4].

Physicians in the United States do not encounter patients with malaria frequently, and the drugs are only available through the CDC, which makes the management of this disease somewhat complicated. Among patients with unexplained fever or clinical deterioration who have traveled to an endemic area, malaria must be included in the differential diagnosis to avoid delays in appropriate treatment of malaria that would increase morbidity and mortality [5,6]. Therefore, it is imperative to have a better understanding of this disease and also to inform readers about the management and ways of improving it.

Case Report

A previously healthy 55-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presented to the Emergency Department (ED) of a hospital in south Florida owing to a fever for 7 days. Fever was quantified with readings of 40°C coming every 48 h, associated with various nonspecific symptoms such as malaise, fatigue, decreased appetite, productive cough for 2–3 days, and abdominal pain with associated watery diarrhea for 2–3 days. The patient’s family reported mental status changes (nonresponsive to her name, visual hallucinations) since symptom onset. The patient denied headache, loss of consciousness, neck rigidity, seizure, focal neurological symptoms, chest pain, hemoptysis, and difficulty breathing at the time of presentation. She denied any similar episodes in the past. She reported allergy (rash) to penicillin. No pertinent family history was noted. She lived with her son, who was asymptomatic, and worked as a biomedical engineer. The patient had returned from a 10-day trip to Ghana 18 days prior to admission, and she had also traveled to California 1 week before admission. She denied receiving malaria prophylaxis or vaccination against yellow fever and hepatitis A virus. She developed symptoms while in California and went to a hospital there, but she was discharged following unremarkable examination and normal laboratory results.

A few hours after arrival to the ED, the patient became lethargic and was found to be in respiratory distress. Vital signs were an oral temperature of 38.6°C, heart rate 121 beats/min, blood pressure 100/51 mmHg, respiratory rate 45 breaths/min, and SpO2 93% on room air. She had dry mucous membranes, decreased bilateral breath sounds, and tenderness to palpation of the left lower quadrant abdomen. No obvious jaundice, enlarged lymph nodes, or splenomegaly was observed. On neurological examination, she was lethargic and confused with Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score of 14 (E4V4M6); her pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light; she had no cranial nerve or sensory deficit; and her neck was supple, with Brudzinski’s and Kernig’s signs both being negative.

Initial laboratory studies revealed leukocytosis with white cell count of 19 800/µL with 44% neutrophils, 22% lymphocytes, and 1% eosinophil; platelets 51 000/µL; hemoglobin 11.8 g/dL; hematocrit 35.3%; red blood cell distribution width 16.9%; lactate dehydrogenase 2714 U/L; haptoglobin <8 mg/dL; prothrombin time/international normalized ratio 14.9/1.4; troponin 0.161 ng/mL; blood glucose 26 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen 157 mg/dL; creatinine 7.52 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate 6 mL/min; bicarbonate 5 mmol/L; anion gap 36; lactic acid 16.2 mmol/L; sodium 131 mmol/L; potassium 5.5 mmol/L; chloride 91 mmol/L; alanine transaminase 542 U/L; aspartate transaminase 1328 U/L; total bilirubin 14.5 mg/dL; and albumin 2.2 mg/dL. A malaria smear was positive with 25% parasitemia initially, and ring forms/trophozoites and a few elongated structures suggestive of developing gametocytes were reported (Figure 1). An arterial blood gas obtained in the ED on 3 L of oxygen via nasal cannula showed pH of 7.03 and pCO2 of 20 and HCO3 of 0.

The patient’s mental status gradually deteriorated while she was being evaluated at the ED. Her GCS score after 3 h of presentation was 10/15 (E2V3M3), and she had to be intubated and mechanically ventilated in the ED for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Severe malaria was diagnosed, consistent with

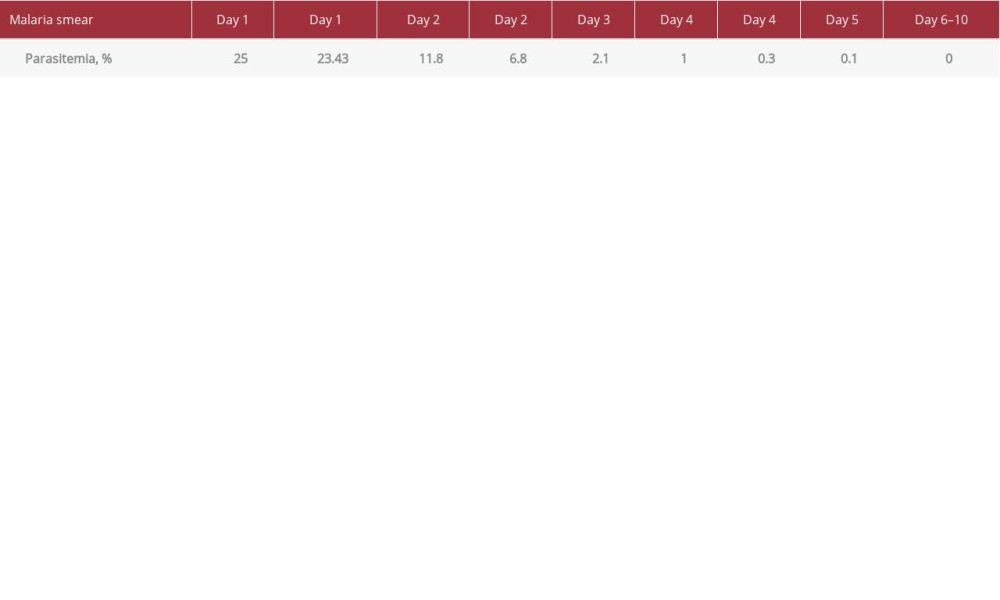

During the second day of admission, the patient had QTc prolongation, so quinidine was switched to IV artesunate every 24 h. The parasitemia and acidosis started improving and the positive end-expiratory pressure and FiO2 requirements decreased. Computed tomography of the brain was unremarkable, and a lumbar puncture showed 3 white blood cells per high-power field, 12% neutrophils, 48% lymphocytes, 38% monocytes, and no organisms on gram stain. Vancomycin and meropenem were discontinued due to no evidence of bacterial meningitis. By the third day of therapy, the parasitemia decreased to 0.3% and was negative on day 6 (Table 1). The multi-organ failure and septic shock were treated with supportive care including renal replacement therapy and platelet transfusions, and the patient was clinically improving. A 5-day course of IV artesunate and doxycycline was completed with an additional 7-day course of oral doxycycline at discharge to a rehabilitation facility with a favorable outcome and recuperation.

Discussion

This case illustrates the need to recognize severe malaria, especially cerebral malaria, and the need for more readily available parenteral artesunate in the United States. Severe malaria is defined as

Treatment of severe malaria requires prompt antimalarial therapy with supportive care and management of complications because mortality is highest in the first 24 h of presentation [8,10,11]. Prompt treatment is especially critical if cerebral malaria is suspected because it has a 15–20% mortality rate when treated and above 30% in cases with multiple vital organ dysfunction [9,12]. For severe malaria, the WHO recommends parenteral artesunate (if the artesunate of reliable quality is available); otherwise, treatment with quinidine is recommended. Quinidine was used in the United States because artesu-nate was neither approved by the FDA nor was it was commercially available before May 2020 [13].

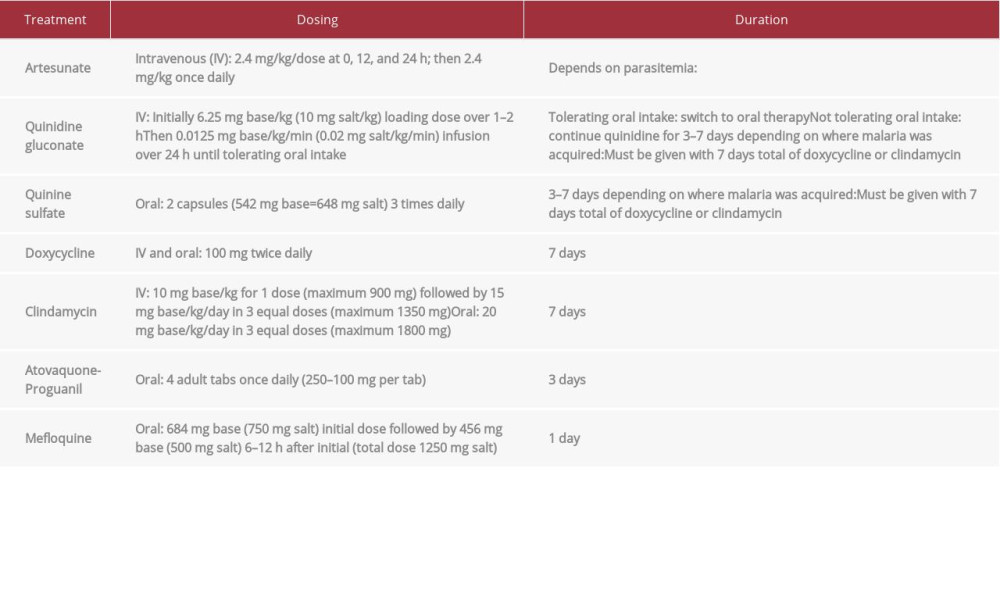

Treatment is generally parenteral initially. It is then completed with oral antimalarial if the patient is tolerating oral intake and parasitemia is ≤1% when using artesunate. Completion of oral antimalarial therapy is 3–7 days afterward depending on the regimen, which can include doxycycline, clindamycin, quinidine, atovaquone-proguanil, and mefloquine (refer to Table 2 for dosing and duration of therapy) [12,14]. Mefloquine should be avoided if the patient has cerebral malaria due to the increased risk of neuropsychiatric effects, and it is not recommended if malaria was acquired in Southeast Asia due to drug resistance [8,12,14].

FDA approval for the use of intravenous artesunate was based on evidence from multiple randomized controlled trials abroad, including Europe, as well as trials in adults and children from endemic areas in Asia and Africa [8,10–13]. The benefits tend to be most pronounced in patients with hyperparasitemia in endemic/nonendemic areas (reduced ICU and hospitalization length of stays). The patients also tend to have faster parasite clearance from the blood by about 1–2 days when treated with artesunate. The difference in outcomes is less pronounced with parasitemia less than 5% [10–14]; nonetheless, adult travelers to endemic areas have a higher likelihood of developing hyperparasitemia, so artesunate would likely still provide a benefit over quinidine. The mechanism of action for artesunate is incompletely understood, but it is hypothesized to involve the formation of free radicals that interfere with parasitic function and it has a broader spectrum of action against ring-stage parasites. By preventing maturation and sequestration of infected erythrocytes, artesunate improves removal by the spleen and allows for less microvascular obstruction and subsequent organ damage. This may explain why the benefits of artesunate are the most profound in patients with hyperparasitemia [10,11,15,16].

The WHO recommends artesunate for the treatment of severe malaria because it has been shown to reduce the adult mortality rate by about 39% relative to quinidine (24% greater reduction in the child mortality rate) [6], has fewer adverse effects and drug-drug interactions, and is easier to dose [9–11]. Quinidine is known to cause QTc prolongation, ototoxic effects, and hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Artesunate is relatively quick acting and tolerated, but patients on this treatment must be monitored for delayed hemolytic anemia at 7, 14, and 30 days after completion of therapy [8,12,14].

The patient presented in this case had severe malaria, specifically cerebral malaria, 18 days after returning to the United States from a 10-day trip to Ghana. Other causes for the patient’s symptoms were excluded, including viral infection, meningitis, bacteremia, and so forth. When the patient was started on quinidine, there was minimal effect on the parasitemia (25% to 23.43% in 24 h). Once treatment was switched to artesunate due to QTc prolongation, the parasitemia dropped from 23.43% to 6.8% in 24 h, and the smear was negative within 5 days. This patient had complications from severe malaria but likely benefited from the faster clearance of malaria from the blood with artesunate, which the quinidine did not provide.

Ideally, this patient could have prevented contracting malaria with mosquito bite prevention and by receiving prophylaxis from a travel clinic, which can provide detailed, individualized, and effective travel counseling. Prophylaxis with atovaquoneproguanil, doxycycline, mefloquine, primaquine, tafenoquine, or rarely chloroquine (due to high rates of resistance) is started prior to travel, and it is continued during the trip and for a period of time after returning home. The regimen depends on the region of travel, length of stay, and local malaria resistance patterns [6,17].

Conclusions

This report presents a case of severe

References:

1.. : Trop Med Int Health, 2014; 19(Suppl. 1); 7-131

2.. : World malaria report 2019, 2019, Geneva, WHO

3.. : About malaria, 2020, Atlanta, GA, CDC https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/index.html

4.. , FDA approves only drug in U.S. to treat severe malaria, 2020 https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-only-drug-us-treat-severe-malaria

5.. Kain KC, Harrington MA, Tennyson S, Keystone JS, Imported malaria: Prospective analysis of problems in diagnosis and management: Clin Infect Dis, 1998; 27(1); 142-49

6.. Gerstenlauer C, Recognition and management of malaria: Nurs Clin North Am, 2019; 54(2); 245-60

7.. Phillips A, Bassett P, Zeki S, Risk factors for severe disease in adults with falciparum malaria: Clin Infect Dis, 2009; 48(7); 871-78

8.. Sinclair D, Donegan S, Isba R, Lalloo DG, Artesunate versus quinine for treating severe malaria: Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012; 2012(6); CD005967

9.. Idro R, Ndiritu M, Ogutu B, Burden, features, and outcome of neurological involvement in acute falciparum malaria in Kenyan children: JAMA, 2007; 297(20); 2232-40

10.. Dondorp A, Nosten F, Stepniewska K, Artesunate versus quinine for treatment of severe falciparum malaria: A randomised trial: Lancet, 2005; 366(9487); 717-25

11.. Dondorp A, Fanello C, Hendriksen I, Artesunate versus quinine in the treatment of severe falciparum malaria in African children (AQUAMAT): An open-label, randomised trial: Lancet, 2010; 376(9753); 1647-57

12.. : Guidelines for the treatment of malaria, 2019, Geneva, WHO

13.. Twomey PS, Smith BL, McDermott C, Intravenous artesunate for the treatment of severe and complicated malaria in the United States: Clinical use under an investigational new drug protocol: Ann Intern Med, 2015; 163(7); 498

14.. : Guidelines for treatment of malaria in the United States, 2019, Atlanta, GA, CDC

15.. Rosenthal PJ, Artesunate for the treatment of severe falciparum malaria: N Engl J Med, 2008; 358(17); 1829-36

16.. Kurth F, Develoux M, Mechain M, Intravenous artesunate reduces parasite clearance time, duration of intensive care, and hospital treatment in patients with severe malaria in Europe: The TropNet Severe Malaria Study: Clin Infect Dis, 2015; 61(9); 1441-14

17.. Tan KR, Arguin PM: Chapter 4 Travel-related infectious diseases Malaria In: CDC yellow book 2020: Health information for international travel, 2020, Atlanta, GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/travel-related-infectious-diseases/malaria

In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942937

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943275

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943411

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250