28 August 2021: Articles

Viscerocutaneous Loxoscelism Manifesting with Myocarditis: A Case Report

Challenging differential diagnosis, Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Travis R. Langner12ACDE, Hammad A. Ganatra12DEF*, Julianne Schwerdtfager1BE, William Stoecker3BC, Stephen Thornton45ACDEDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.932378

Am J Case Rep 2021; 22:e932378

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Envenomation from the brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) is described to cause both local and systemic symptoms. We report a case of an adolescent boy who developed severe systemic loxoscelism, and his clinical course was complicated by myocarditis, which has not been previously reported in association with loxoscelism.

CASE REPORT: A 16-year-old boy presented with non-specific symptoms and forearm pain following a suspected spider bite, which subsequently evolved into a necrotic skin lesion. During his clinical course, he developed a characteristic syndrome of systemic loxoscelism with hemolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome, necessitating transfer to the Intensive Care Unit. The diagnosis was confirmed with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay that detected Loxosceles venom in the wound. Additionally, he developed pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock secondary to myocarditis, which was confirmed with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Steroids and plasmapheresis were initiated to manage the severe inflammatory syndrome, and the myocarditis was treated with intravenous immunoglobulins, resulting in resolution of symptoms and improvement of cardiac function.

CONCLUSIONS: This is the first reported case of myocarditis associated with loxoscelism, providing evidence for Loxosceles toxin-associated cardiac injury, which has been previously described in animal models only. Furthermore, this case provides further support for the use of confirmatory testing in the clinical diagnosis of loxoscelism.

Keywords: Brown Recluse Spider, Loxosceles Venom, myocarditis, Plasmapheresis, Adolescent, Animals, Hemolysis, Humans, Skin Diseases, Spider Bites

Background

Brown recluse spiders (

Case Report

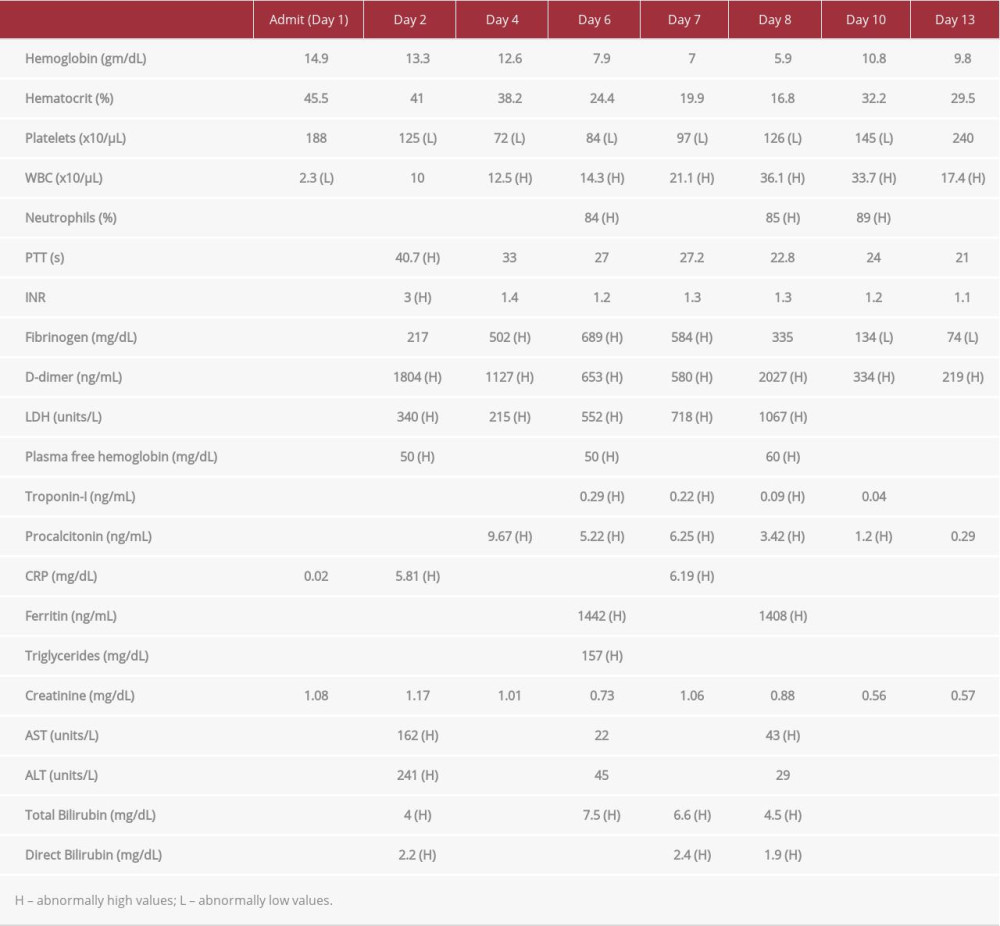

A previously healthy 16-year-old male resident of western Missouri presented to the Emergency Department with sore throat, fatigue, myalgias, fever, and left forearm soreness for 1 day. Initial vital signs revealed a temperature of 39.1°C, heart rate of 143 beats per min, and normal respiratory rate, pulse oximetry, and blood pressure. The physical examination revealed a fatigued-appearing teenager with dry mucus membranes and mild cervical lymphadenopathy. A throat examination showed mild erythema of the posterior pharyngeal wall but without exudate. Auscultation revealed a normal lung examination and normal cardiac examination with tachycardia. Mild tenderness was appreciated on his left forearm, which otherwise appeared unremarkable and demonstrated full range of motion. Initial laboratory tests were unremarkable, aside from an elevated creatinine level (Table 1).

Blood cultures were obtained, and he was started on vancomycin and ceftriaxone empirically and admitted for possible sepsis. On hospital day 2, the patient’s forearm soreness evolved into a swollen, tender, and erythematous area, and he recalled sleeping in a basement where spiders were noted. He developed worsening hypotension (blood pressure decreased from 109/53 to 82/39 mmHg over a 12-h period) with persistent tachycardia (heart rate, 130–145 beats per min) and was unresponsive to a fluid challenge, requiring transfer to the pediatric Intensive Care Unit for management of decompen-sated shock. Ionotropic support was initiated, and intra-arterial access was obtained for continuous blood pressure monitoring. Repeat laboratory examination showed transaminitis, with increased bilirubin and C-reactive protein, leukocytosis, and coagulation profile consistent with DIC (Table 1). Owing to worsening hypotension and a concern for a spider bite, the differential diagnosis at this point was septic shock vs loxoscelism.

The medical toxicology department was consulted and agreed with the diagnosis of loxoscelism. Over hospital days 3 to 5, the patient’s left arm became increasingly tender, developing vesicular areas over a darkening, necrotic-appearing base (Figure 1). A skin swab from the lesion was submitted for an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect

His clinical status acutely worsened on day 6, with hemoglobin dropping precipitously from 12.6 gm/dL to 7.9 gm/dL, and a concomitant increase in LDH, bilirubin, and plasma free hemoglobin suggested intravascular hemolysis. The patient was transfused with packed red blood cells, and methylpredniso-lone was initiated in an attempt to slow hemolysis. He also developed tachycardia with diffuse T-wave changes on electrocardiogram (EKG), which were concerning for myocarditis. B-type natriuretic peptide, troponin-I, and creatine kinase-muscle/brain levels were elevated to 1309 pg/mL, 0.29 ng/mL, and 7.6 ng/mL, respectively, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated myocarditis involving the left ventricular apex and the basal portion of the heart, with an ejection fraction of 45% (Figure 2). Myocarditis therapy was initiated with intravenous immunoglobulins and bumetanide was administered to reduce pulmonary edema and volume overload. He demonstrated a favorable clinical response to therapy, along with steadily decreasing troponin-I and B-type natriuretic peptide, normalization of EKG (Figure 3), and improved cardiac function on repeat echocardiogram performed a week later.

Despite ongoing steroidal treatment, the patient’s hemoglobin reached a nadir of 5.9 gm/dL, requiring further transfusions on hospital days 7 and 8. Plasmapheresis was then performed on days 8, 9, 10, and 13. His hematological laboratory results normalized thereafter, and remained stable for the remainder of his hospitalization. His laboratory values continued improving over the subsequent week, and he was discharged home on day 20. His wound responded to standard outpatient wound care (Figure 4), and a follow-up outpatient echocardiogram was normal.

Discussion

We present a case of severe viscerocutaneous loxoscelism in an adolescent patient with characteristic hemolysis, DIC, and severe systemic inflammatory response as well as previously unreported myocarditis. Diagnosis of loxoscelism envenomation typically depends on clinical presentation, with emphasis on history and physical examination [3,5,6]. Although not commercially available, the ELISA developed at the University of Missouri and used in this case has been previously detailed in the medical literature [7,8]. It is performed on skin swabs obtained from a suspected

The mechanism for development of viscerocutaneous loxoscelism is not fully understood but is suspected to involve multiple molecular and cellular pathways [6,10,11]. The venom itself contains sphingomyelinase-D and alkaline phosphatase and is capable of creating an immune response through complement, neutrophil, and platelet activation as well as by activating collagenase, proteases, esterase, ribonuclease, and deoxyribonuclease [3,6,11]. The toxin causes direct hemolysis via activation of metalloproteinases that cleave glycophorins from red blood cell surfaces to make them targets for complement lysis [6].

Myocarditis is defined as inflammation of the myocardium, with a wide spectrum of clinical presentation that can range from subclinical disease to fulminant circulatory failure and death [16]. Moreover, survivors of mild to moderate disease can progress to significant morbidity with dilated cardiomyopathy [17]. The clinical picture of myocarditis can be characterized by cardiovascular dysfunction, shock, tachycardia, chest pain, arrhythmias, and pulmonary edema and is supported by laboratory markers of myocardial injury (elevated troponin and creatine kinase-muscle/brain levels) and concurrent inflammation (elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate) [16,18]. Endomyocardial biopsy has historically been the diagnostic criterion standard for myocarditis, but its relatively poor sensitivity and invasive nature and the concurrent risks of anesthesia have made it controversial in current clinical practice. Cardiovascular MRI is now regarded as the noninvasive criterion standard for diagnosing myocarditis [16], allowing noninvasive visualization of myocardial inflammation and ventricular function [17,18]. Our patient’s diagnosis and cardiac function was also confirmed with cardiovascular MRI, and therapy was initiated with intravenous immunoglobulins. Follow-up MRI was not deemed necessary at the time owing to marked clinical improvement following therapy, and is generally not recommended [16]. However, improved cardiac function was demonstrated on follow-up echocardiograph.

Although

Conclusions

In summary, this case highlights previously described features of viscerocutaneous loxoscelism, such as severe inflammatory response, hemolysis, and DIC. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the first reported case of myocarditis associated with loxoscelism, providing new evidence for

Figures

References:

1.. Gertsch WJ, Ennik F, The spider genus Loxosceles in North America, Central America, and the West Indies (Araneae, Loxoscelidae): Bulletin of the AMNH, 1983; 175 article 3

2.. Vetter RS, Arachnids submitted as suspected brown recluse spiders (Araneae: Sicariidae): Loxosceles spiders are virtually restricted to their known distributions but are perceived to exist throughout the United States: J Med Entomol, 2005; 42(4); 512-21

3.. Hogan CJ, Barbaro KC, Winkel K, Loxoscelism: Old obstacles, new directions: Ann Emerg Med, 2004; 44(6); 608-24

4.. Elbahlawan LM, Stidham GL, Bugnitz MC, Severe systemic reaction to Loxosceles reclusa spider bites in a pediatric population: Pediatr Emerg Care, 2005; 21(3); 177-80

5.. Hubbard JJ, James LP, Complications and outcomes of brown recluse spider bites in children: Clin Pediatr (Phila), 2011; 50(3); 252-58

6.. de Souza AL, Malaque CM, Sztajnbok J, Loxosceles venom-induced cytokine activation, hemolysis, and acute kidney injury: Toxicon, 2008; 51(1); 151-56

7.. Stoecker WV, Green JA, Gomez HF, Diagnosis of loxoscelism in a child confirmed with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and noninvasive tissue sampling: J Am Acad Dermatol, 2006; 55(5); 888-90

8.. Stoecker WV, Wasserman GS, Calcara DA, Systemic loxoscelism confirmation by bite-site skin surface: ELISA: Mo Med, 2009; 106(6); 425-27

9.. Gomez HF, Krywko DM, Stoecker WV, A new assay for the detection of Loxosceles species (brown recluse) spider venom: Ann Emerg Med, 2002; 39(5); 469-74

10.. Levin C, Bonstein L, Lauterbach R, Immune-mediated mechanism for thrombocytopenia after Loxosceles spider bite: Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2014; 61(8); 1466-68

11.. Swanson DL, Vetter RS, Loxoscelism: Clin Dermatol, 2006; 24(3); 213-21

12.. Zanetti VC, da Silveira RB, Dreyfuss JL, Morphological and biochemical evidence of blood vessel damage and fibrinogenolysis triggered by brown spider venom: Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis, 2002; 13(2); 135-48

13.. Lane L, McCoppin HH, Dyer J: Pediatr Dermatol, 2011; 28(6); 685-88

14.. Abraham M, Tilzer L, Hoehn KS, Thornton SL: J Med Toxicol, 2015; 11(3); 364-67

15.. Said A, Hmiel P, Goldsmith M, Dietzen D, Hartman ME, Successful use of plasma exchange for profound hemolysis in a child with loxoscelism: Pediatrics, 2014; 134(5); e1464-67

16.. Dasgupta S, Iannucci G, Mao C, Myocarditis in the pediatric population: A review: Congenit Heart Dis, 2019; 14(5); 868-77

17.. Martins DS, Ait-Ali L, Khraiche D, Evolution of acute myocarditis in a pediatric population: An MRI based study: Int J Cardiol, 2021; 329; 226-33

18.. Guglin M, Nallamshetty L, Myocarditis: Diagnosis and treatment: Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med, 2012; 14(6); 637-51

19.. Martin Nares E, Lopez Iniguez A, Ontiveros Mercado H, Systemic lupus erythematosus flare triggered by a spider bite: Joint Bone Spine, 2016; 83(1); 85-87

20.. Dias-Lopes C, Felicori L, Guimaraes G: Toxicon, 2010; 56(8); 1426-35

21.. Ayach B, Fuse K, Martino T, Liu P, Dissecting mechanisms of innate and acquired immunity in myocarditis: Curr Opin Cardiol, 2003; 18(3); 175-81

22.. Chaudhuri A, Dooris M, Woods ML, Non-rheumatic streptococcal myocarditis – warm hands, warm heart: J Med Microbiol, 2013; 62(Pt 1); 169-72

Figures

In Press

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943275

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943411

13 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942864

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250