12 December 2021: Articles

Warm Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia as the Initial Presentation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): A Case Report

Unknown etiology, Challenging differential diagnosis

Tejaswi Kanderi1ABCDEF*, Jinah Kim1ABCE, Janet Chan Gomez1ABE, Maria Joseph1BDE, Binita Bhandari1ADEDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.932965

Am J Case Rep 2021; 22:e932965

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Autoimmune hemolytic anemia is an acquired disorder resulting in the presence of antibodies against red blood cell (RBC) antigens causing hemolysis. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia is of 2 types, Warm antibody mediated and cold agglutinin disease. Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia (warm agglutinin disease) usually presents with fatigue and other constitutional symptoms and is diagnosed by the presence of IgG antibodies. The disease can occur as idiopathic or secondary to other autoimmune diseases, infections, or even malignancies. The systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease prevalent in young females. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia can occur as a part of the SLE spectrum however warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia as the initial manifestation of SLE is extremely rare.

CASE REPORT: Here, we describe a unique case of a 32-year-old woman who presented with vague clinical presentation found to have warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia and further immunological and inflammatory work-up during and after hospitalization lead to the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus.

CONCLUSIONS: The systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune chronic inflammatory disease with unclear etiology affecting multi organs. Variable presentation in addition to the lack of definite pathognomonic features or tests makes the diagnosis of SLE challenging. On the whole autoimmune hemolytic anemia can not only be part of other disease processes but can be an initial presentation, highlighting the importance of thorough work-up in patients presenting with autoimmune hemolytic anemia to aid in timely diagnosis and management of underlying secondary conditions. It is important for providers to be aware of various disease spectrums that contain autoimmune hemolytic anemia for day-to-day clinical practice.

Keywords: Anemia, Hemolytic, Anemia, Hemolytic, Autoimmune, Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic, Pericarditis, Spherocytes, Female, Hemolysis, Humans, Immunoglobulin G

Background

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia is a rare acquired disorder characterized by autoantibodies against red cell proteins resulting in hemolysis and anemia due to a decrease in the RBC life span [1]. It can be caused by warm, cold, or mixed antibodies [2]. AIHA can occur as idiopathic (primary) or secondary to other malignancies (leukemia, lymphoma, or solid tumors), infections, or even autoimmune diseases [1,3]. Incidence is 1 to 3 out of 100,000 patients per year, out of which 70–80% are caused by warm autoantibodies resulting in warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia (wAIHA) [3]. About half of all w AIHA cases are secondary to the above conditions [3]. AIHA may be suspected with relevant history (symptoms of anemia), routine lab work (CBC, Reticulocyte count, LDH, haptoglobin, peripheral smear etc) and Direct antiglobulin test. AIHA is diagnosed by a positive direct antiglobulin test (direct Coombs test) in the absence of other possible causes of hemolysis. A positive direct antiglobulin may be found in less than 0.1% of healthy blood donors and 0.3–8% of hospitalized patients who do not have AIHA. Secondary AIHA may also occur in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and it is reported that 10% of SLE patients have wAIHA however wAIHA as the initial presentation of SLE is rare. Sometimes, severe SLE may follow years after AIHA [4]. Two-third of patients with AIHA have a response to first-line therapy of steroids; however, relapses are common and require slow careful tapering and close monitoring [5].

Case Report

A previously untransfused 32-year-old obese Hispanic gravida 1 para 1 woman with no significant medical history presented to the Emergency Department with fatigue, worsening of generalized weakness, and shortness of breath on exertion for the past 2 months with worsening of symptoms for the past 2 weeks. The patient also endorsed nausea, decreased food intake, and dark stools during the same period of time. She was a former smoker with 16 pack-year history and quit 2 months ago. She denied taking any medications or supplements except iron supplements, which she started taking on her own. She had no family history of autoimmune diseases.

Vitals on presentation were temperature 37°C (98.6°F), heart rate of 118 beats/min, blood pressure of 170/102 mm of Hg, respiratory rate of 20 per minute, and oxygen saturation 100% on room air. Anicteric sclera and 1+ pitting edema on both lower extremities were noted. Lungs were clear to auscultation and the abdomen was soft, non-tender, with normal bowel sounds. No rash was identified.

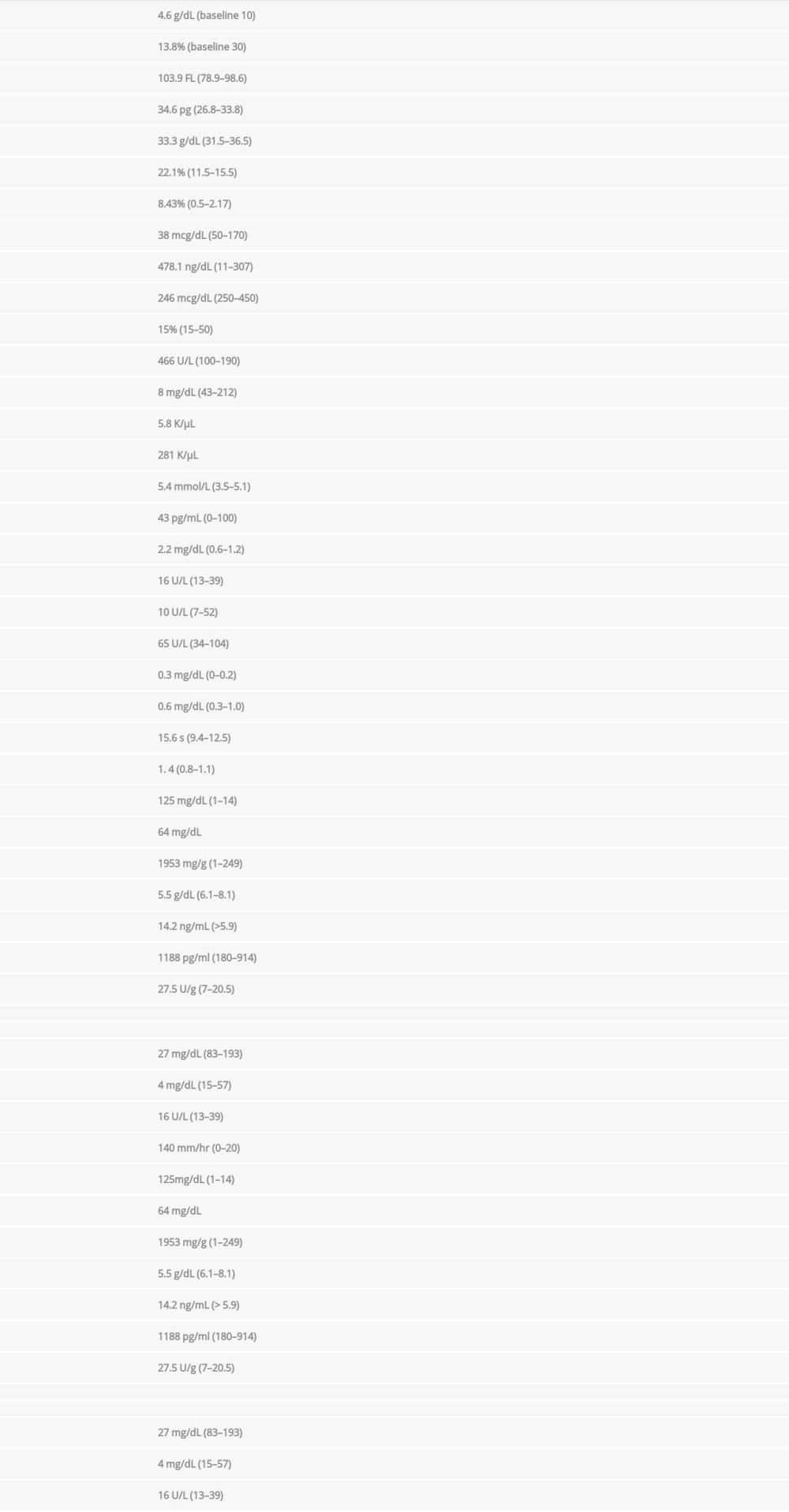

EKG showed sinus tachycardia and a chest X-ray revealed interstitial edema, mild cardiomegaly, and possible pericardial effusion (Figure 1).

A COVID-19 PCR test was negative. Type and screen and cross-match process revealed A+ blood group with positive Coombs with warm antibodies in addition to several other antibodies. The atient was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit for close monitoring of hemodynamics and transfusion reactions. While the patient was managed with typed/screened and cross-matched blood transfusion and intravenous steroids, methylprednisolone was (1 mg/kg) given 30 min before the blood transfusion additional hematology and rheumatology work-ups were continued. ANA screen showed 1: 640 (<1: 40 negative, >80 elevated) titer with homogenous nuclear pattern (typically associated with SLE or drug-induced lupus). Anti-cardiolipin Ig M was elevated at 32 (<11 negative, >80 high positive), while both Ig A and IgG were negative. Rheumatoid factor and RPR were negative. Anti-ds DNA was 259 IU/ml (reference <4). HIV, hepatitis B surface antigen, and Hep C antibody are nonreactive. Table 1 shows all lab results since presentation.

A peripheral smear showed spherocytes, +2 anisocytosis, +1 macrocytes, poikilocytes, ovalocytes, and teardrop cells (Figure 2).

ECHO (ultracardiography) revealed normal EF (ejection fraction) of 50–55% moderate circumferential pericardial effusion with no definite feature of tamponade (Figure 3). CT chest abdomen and pelvis without contrast revealed a new, thick, small pericardial effusion (Figure 4).

Gastroenterology was consulted for endoscopy, which revealed gastritis without a bleeding source. A biopsy from the antrum and duodenum revealed no pathology and was negative for

The patient underwent a left renal biopsy after discharge, which is consistent with lupus nephritis III/IV with immune complex-mediated proliferative glomerulonephritis, glomerulosclerosis, and arteriolar hyalinosis. Interestingly, the patient presented to the ED with left flank pain 1 week after biopsy, with CT abdomen with contrast revealing left perinephric hematoma with contrast extravasation requiring emergent embolization, sacrificing approximately 20% of the left kidney. The spontaneous hemorrhage was likely secondary to the percutaneous renal biopsy (Figure 5).

Discussion

Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia occurs due to IgG antibodies causing hemolysis through Fc-mediated extravascular phagocytosis of the IgG-coated red blood cells (RBC) in the spleen, resulting in spherocytes due to loss of RBC membrane [6]. DAT is useful in differentiating immune- from non-immune-mediated hemolytic anemia [7].

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory disease with unclear etiology, affecting multiple organs. Its variable presentation and lack of definite pathognomonic features or tests makes the diagnosis of SLE challenging. Isolated symptom presentation makes the diagnosis much harder unless differentials are broad and a thorough work-up is done. Like any other autoimmune condition, SLE primarily affects women of childbearing age, like our patient. It is also reported to be more common in certain racial groups, including Hispanics and African Americans, than in Whites, which fits our patient [8].

Hematological manifestations occur in SLE affecting all 3 cell lines causing anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leucopenia with anemia being the most common entity. The etiology of anemia is reported as multifactorial, including anemia of chronic disease, autoimmune hemolysis, renal disease, or treatment-induced. Autoimmune hemolysis occurs in less than 10% of patients with SLE. Hemolytic anemia can occur years before or after a diagnosis of SLE is made, and rarely as an initial presenting feature of SLE [9,10]. Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia is more common than cold agglutinin type. No specific diagnostic criteria exist for hemolytic anemia; however, the diagnosis is made if no other cause of anemia is identified in the presence of signs of RBC destruction (eg, elevated LDH, unconjugated bilirubin, low haptoglobin), signs of accelerated RBC production (eg, increased reticulocyte count), positive DAT test, and peripheral smear with schistocytes or spherocytes.

Both the 2019 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) classification criteria include hemolytic anemia as one of the diagnostic criteria for SLE [2].

Below is the application of ACR criteria to our patient (a score of at least 10 indicates SLE).

Entry criteria: Positive for ANA (Antinuclear antibody) at a titer of greater than or equal to 1: 80.

Additive criteria:Autoimmune hemolysis Score 4;Serosal, pericardial effusion Score 5;Proteinuria >0.5 g/24 h Score 4;Antiphospholipid antibodies (anticardiolipin) Score 2;Complement proteins, low C3 and C4 Score 4;SLE-specific antibody, anti-dsDNA Score 6. (double-stranded DNA)

With a total score of 25, our patient met the criteria for diagnosis.

Our patient also met the criteria of SLE per 2012 SLICC with the following positive findings.Lupus nephritis: ANA;Clinical criteria: Serositis, renal and hemolytic anemia;Immunological criteria: ANA, Anti-dsDNA, antiphospholipid antibody, low complement, positive direct Coombs test.

Although both the criteria were met in our case, depending on the turnaround times for different tests, a presumed diagnosis is often made with pending work-up; thus, high suspicion and awareness of rare presentations of SLE are needed among clinicians. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia can be part of another autoimmune disease spectrum; therefore, identifying it as part of other disease processes and considering wide differential is important.

A retrospective study including 89 patients with wAIHA in a single center in Mexico revealed 77% of secondary wAIHA occurred in females, with an average age of 36 years, correlating with the prevalence of autoimmune diseases in females in the age range, denoting that wAIHA may have a significant association with autoimmune diseases in Hispanic populations, as discovered in our patient [11]. Further research in a specific population is needed to confirm the findings.

A retrospective cohort analysis of 60 patients with wAIHA in France reported significantly lower hemoglobin in secondary wAIHA than in primary wAIHA (6 vs 7 g/dl) with secondary causes as lymphoproliferative disorders and SLE similar to very low hemoglobin in our patient on presentation. However, considering secondary wAIHA in patients with very low hemoglobin needs further evidence in terms of the threshold of hemoglobin for the primary vs secondary variety [12].

Anticardiolipin antibodies (ACA) occur in approximately 40% of patients with SLE, but ACA can be present in AIHA with or without SLE, suggesting the role of ACA in both primary and secondary AIHA. Data regarding levels of IgG and IgM are not clear, with 1 study reporting elevated IgM and normal IgG levels, similar to our patient [9,13,14].

Spontaneous hemorrhage is likely a complication from renal biopsy itself; however, Wunderlich syndrome, a rare form of perinephric or nephric bleeding commonly associated with benign (angiomyolipoma) or malignant tumors (renal cell carcinoma) that can also present as lupus-associated vasculitis is worth mentioning in the context of our patient [15,16].

Treatment of wAIHA in SLE is based on a few retrospective analyses and rare case reports in which the results of idiopathic AIHA were extrapolated to AIHA secondary to SLE, leading to similar treatment options like corticosteroids, steroid-sparing immunomodulators like Rituximab, splenectomy, and immunoglobulins (IVIg) [1,9,11,17]. The steroid response rate in secondary wAIHA is reported to be around 80%; however, approximately 60% of patients lose response with weaning or discontinuation of steroids, requiring prolonged therapy or slow tapering with close surveillance [17].

Conclusions

wAIHA should be approached with a wide differential to avoid delay in the appropriate management of primary disease in case one exists. Although warm agglutinin disease as an initial presentation of SLE is rare, a high degree of suspicion followed by thorough investigation among clinicians is needed for accurate diagnosis and timely management. We aimed to highlight the importance of utilizing clinical criteria to aid in the diagnosis of autoimmune diseases, especially in cases with vague presentations.

Figures

References:

1.. Liebman HA, Weitz IC, Autoimmune hemolytic anemia: Med Clin North Am, 2017; 101(2); 351-59

2.. Mohanty B, Ansari MZ, Kumari P, Sunder A, Cold agglutinin-induced hemolytic anemia as the primary presentation in SLE – a case report: J Family Med Prim Care, 2019; 8(5); 1807-8

3.. Kalfa TA, Warm antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia: Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2016; 2016(1); 690-97

4.. , Kelley and Firestein’s Textbook of Rheumatology Available from: https://www.elsevier.com/books/kelley-and-firesteins-textbook-of-rheumatology/9780323316965

5.. Bass GF, Tuscano ET, Tuscano JM, Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune hemolytic anemia: Autoimmun Rev, 2014; 13(4–5); 560-64

6.. Gerber B, Schanz U, Stüssi G, [Autoimmune hemolytic anemia]: Ther Umsch, 2010; 67(5); 229-36 [in German]

7.. Valent P, Lechner K, Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune haemolytic anaemias in adults: A clinical review: Wien Klin Wochenschr, 2008; 120(5–6); 136-51

8.. Lim SS, Drenkard C, Epidemiology of lupus: An update: Curr Opin Rheumatol, 2015; 27(5); 427-32

9.. Velo-García A, Castro SG, Isenberg DA, The diagnosis and management of the haematologic manifestations of lupus: J Autoimmun, 2016; 74; 139-60

10.. Kokori SI, Ioannidis JP, Voulgarelis M, Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Am J Med, 2000; 108(3); 198-204

11.. Alonso H-C, Manuel A-AV, Amir CGC, Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia: Experience from a single referral center in Mexico City: Blood Res, 2017; 52(1); 44-49

12.. Roumier M, Loustau V, Guillaud C, Characteristics and outcome of warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia in adults: New insights based on a single-center experience with 60 patients: Am J Hematol, 2014; 89(9); E150-55

13.. Fong KY, Loizou S, Boey ML, Walport MJ, Anticardiolipin antibodies, haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia in systemic lupus erythematosus: Br J Rheumatol, 1992; 31(7); 453-55

14.. Staropoli JF, Van Cott EM, Makar RS, Membrane autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus: A case of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, antiphospholipid antibodies, and transient acquired activated protein C resistance: Transfusion, 2008; 48(11); 2435-41

15.. Chen HY, Wu KD, Chen YM, Vasculitis-related Wunderlich’s syndrome treated without surgical intervention: Clin Nephrol, 2006; 66(4); 291-96

16.. Chao CT, Wang WJ, Ting JT, Wünderlich syndrome from lupus-associated vasculitis: Am J Kidney Dis, 2013; 61(1); 167-70

17.. Hill A, Hill QA, Autoimmune hemolytic anemia: Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2018; 2018(1); 382-89

Figures

In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942966

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942032

06 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942937

12 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943244

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250