14 June 2022: Articles

A 39-Year-Old Woman with Ventricular Electrical Storm Treated with Emergency Cardiac Defibrillation Followed by Multidisciplinary Management

Unusual clinical course, Unusual setting of medical care

Piotr Sielatycki1ABEF, Małgorzata Chlabicz23ADEF*, Robert Sawicki4BC, Tomasz Hirnle5BC, Bożena Sobkowicz4BDE, Karol A. KamińskiDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.935710

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935710

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Ventricular electrical storm (VES) is a treatment-resistant ventricular arrhythmia associated with high mortality. This report is of a 39-year-old woman with VES treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management.

CASE REPORT: A 39-year-old woman, previously diagnosed with eosinophilia of unknown origin and recurrent non-sustained ventricular tachycardias, was admitted to the Department of Invasive Cardiology with VES after an initial antiarrhythmic approach, analgesia, and defibrillation in the Emergency Department. The patient had a temporary pacing wire implanted, but overdrive therapy was not successful. The medical treatment and multiple defibrillations did not stop the arrythmia. Due to the hemodynamic instability, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was performed at the Department of Cardiac Surgery. Consequently, the patient was stabilized and an electrophysiology exam and RF ablation of arrhythmogenic focus were conducted in the Department of Cardiology. One day after the procedure, the patient had pulmonary edema caused by pericardial tamponade. The patient was successfully operated on in the Department of Cardiac Surgery. Then, the next complication appeared – a femoral artery embolism – which was treated in the Department of Vascular Surgery. After patient stabilization and exclusion of serious neurological damage, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was implanted for secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD).

CONCLUSIONS: This case has shown the importance of the rapid diagnosis of VES and emergency management with cardiac defibrillation. Multidisciplinary clinical follow-up is required to investigate and treat any reversible causes and to ensure long-term stabilization of cardiac rhythm.

Keywords: Cardiac Tamponade, case reports, Catheter Ablation, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, Tachycardia, Ventricular, Adult, Anti-Arrhythmia Agents, Arrhythmias, Cardiac, Death, Sudden, Cardiac, Defibrillators, Implantable, Female, Humans

Background

Ventricular electrical storm (VES) is a sustained ventricular arrhythmia (VA) recurrent over a short period of time [1]. The most widely accepted definition of VES is 3 or more episodes of sustained VA occurring within 24 h [1]. VES is associated with high mortality in the acute phase and is also an independent factor which increases morbidity in a 3-month observation [2]. The most frequent triad of factors behind VES are: (1) acquired and congenital predisposal as myocardial scars or hereditary arrhythmogenic syndromes; (2) autonomic nervous system disorders as increased of sympathomimetic activation or excessive suppression of parasympathetic nervous system; and (3) triggers such as ischemia, inflammation, hypoxemia, dyselectrolitemia, and toxicosis [1]. Moreover, the factors increasing the risk of VES are male sex, a lower ejection fraction of the left ventricle, and serious comorbidities [3]. Case reports on VES mainly concern patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) where arrythmias were primary treated by a device intervention.

Nevertheless, implantation of an ICD is the ultimate approach in a secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death and does not solve the problem [1]. VES is related with high pre-hospital mortality in patients with VA and cardiac arrest who were not previously diagnosed with serious heart muscle defects. A comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment of VES is important. This report is of a 39-year-old woman with VES treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management.

Case Report

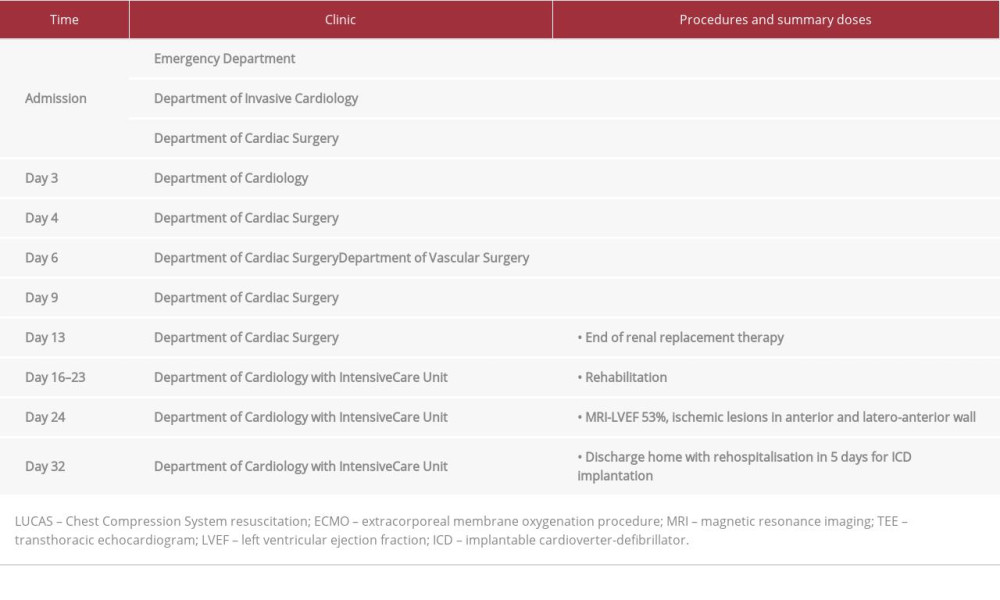

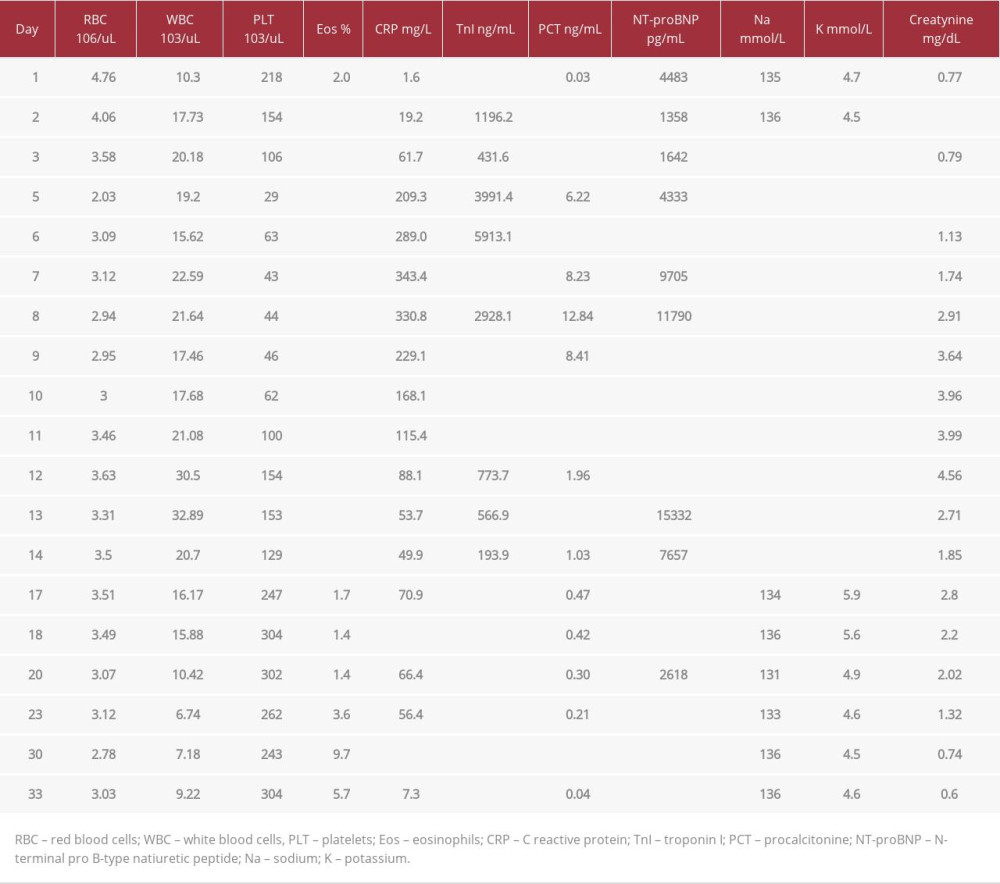

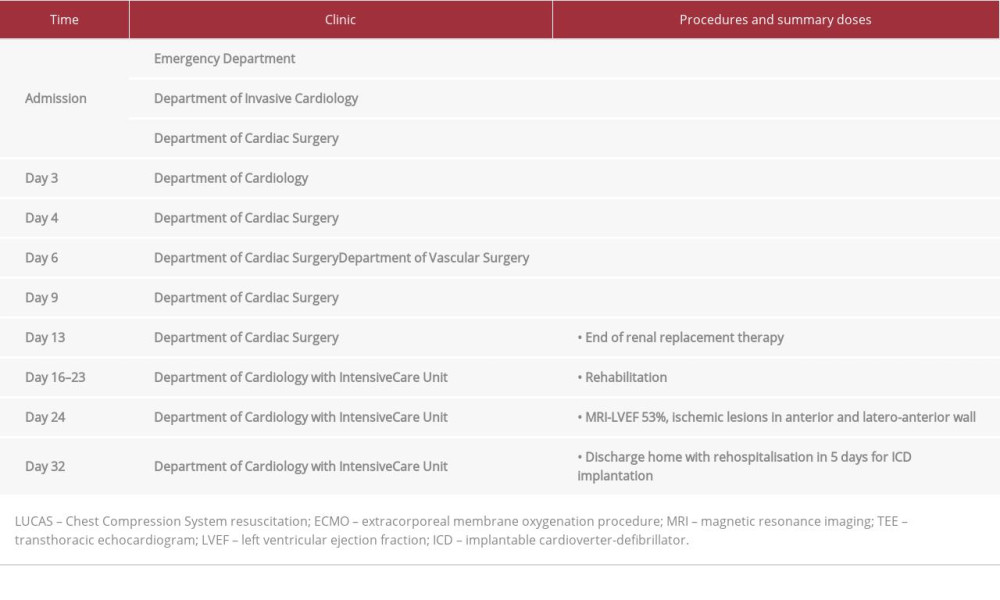

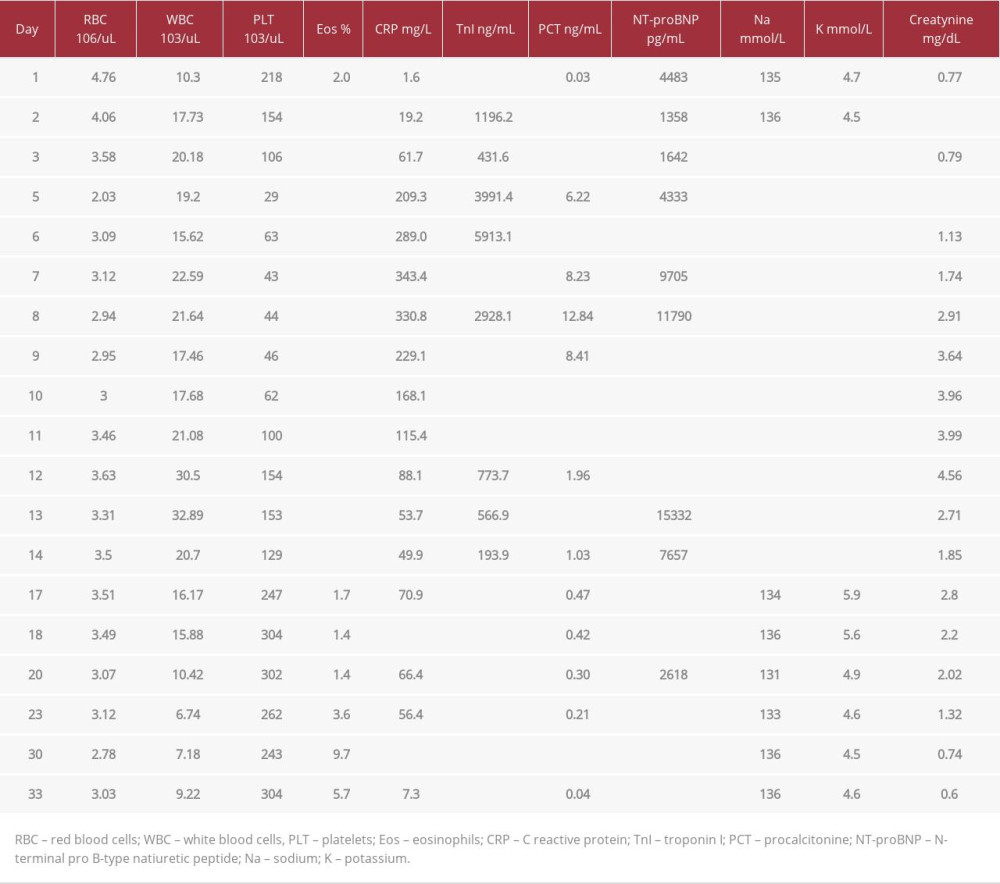

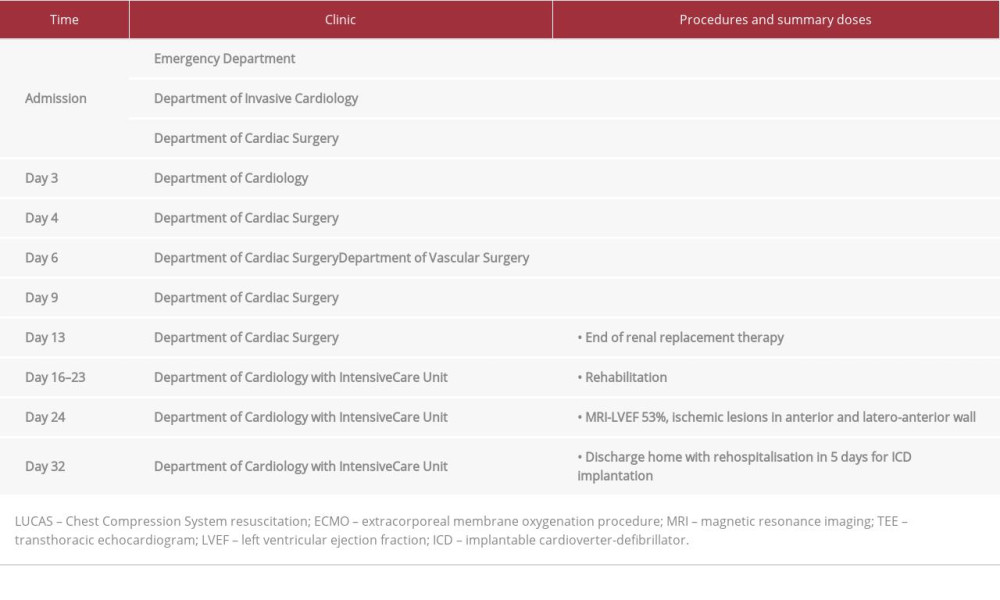

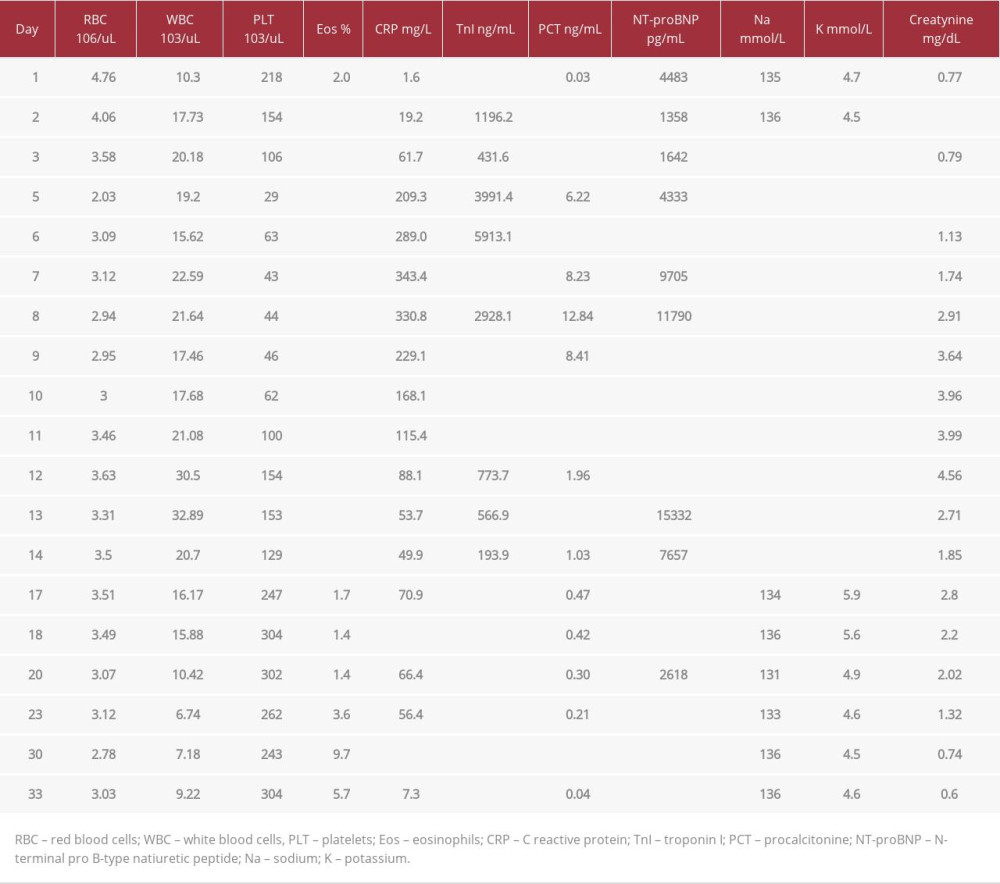

A 39-year-old woman was admitted to the Department of Invasive Cardiology with VES after an initial antiarrhythmic approach, analgesia, and defibrillation in the Emergency Department (ED). The timeline of subsequent events is shown in Table 1. The patient had no history of smoking or abuse of alcohol or drugs. The medical history from the previous year revealed ventricular arrhythmias in the form of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (nsVT) detected by Holter monitoring and eosinophilia of an unknown cause despite in-depth diagnostics. In the outpatient transthoracic echocardiographic (TTE) examination, no valvular defect nor segmental abnormalities of the contractility of the left ventricle were found; the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 65%. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the heart performed 1 year prior to the events showed neither fibrosis foci nor active and past post-inflammatory changes, and left ventricular ejection fraction was preserved. An electrocardiogram (ECG) recorded 3 weeks before the present admission revealed ventricular bigemina (Figure 1A). No features related to hereditary electrical disease were found in normal sinus beats. Additionally, the patient was taking 2.5 mg of bisoprolol daily. On the day of admission, the patient was reported to have fainted twice without a complete loss of consciousness, which was the reason for contacting the ambulance services. During patient transport, ventricular tachycardia with a preserved pulse developed and treatment with boluses of amiodarone failed to resolve the arrhythmia. Despite preserved awareness, the patient’s condition gradually deteriorated, and on admission to the ED was defined as moderately severe. Her blood pressure was 96/65 mmHg, Glasgow coma scale (GCS) was 15 points, and the ECG showed monomorphic ventricular tachycardia 203/min (Figure 1B). VT-inducing factors such as drugs, acute cardiac ischemia, and electrolyte disturbances were excluded. Laboratory tests showed no dyselectrolytemia, no inflammation, and no elevated markers of myocardial damage. Subsequently, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was negative. Due to the history of eosinophilia, the number of eosinophils was checked, and it was normal (210/µl). Only a significantly increased value of the N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was found (Table 2). The attempts to terminate arrhythmias with amiodarone, metoprolol, lignocaine, magnesium sulfate, and adenosine were unsuccessful. Due to her deteriorating hemodynamic state, the patient was sedated, intubated, and mechanically ventilated. Electrical cardioversion was then attempted 4 times but failed to restore stable sinus rhythm. Then, the arrhythmia turned to ventricular fibrillation (VF), which required Lund University Cardiopulmonary Assist System (LUCAS) chest compression system-based resuscitation; defibrillation was performed, resolving the hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia. A decision was made to implant an endocavitary electrode for temporary cardiac pacing in the Department of Invasive Cardiology. The patient was transferred to the Intensive Cardiac Care Unit (ICCU), where alternating pulses of pulseless ventricular tachycardia, ventricular pacing, and ventricular fibrillation were present. In the TTE examination, no valvular defects were found; LVEF measured 40%. Subsequent attempts at antiarrhythmic treatment, cardioversion, and defibrillation were unsuccessful (30 electro-cardioversions and defibrillations were performed). After central venous catheter insertion, a vasopressor and positive inotropic amines were administered. An attempt to terminate the arrhythmia with overdrive stimulation was unsuccessful.

Due to the exhaustion of therapeutic options and prolonged resuscitation, the decision was made to provide hemodynamic support with peripheral V-a extracorporeal membrane oxygenation procedure (ECMO) in the Department of Cardiac Surgery. No intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was implanted at this critical stage, as it seemed it would not be effective and would only prolong organ ischemia time. IABP is quite applicable with a fairly slow and steady rhythm. However, due to the problem of synchronization with the rhythm in fast VT and VF, ECMO seemed to be the better solution. After cardiovascular support, the patient’s condition and hemodynamic parameters were stabilized. Laboratory tests revealed features of acute myocardial and renal damage related to prolonged resuscitation actions, as well as increased inflammatory parameters requiring empiric antibiotic therapy. The ventricular arrhythmia persisted, so the decision was made to perform coronary angiography in the Department of Invasive Cardiology and then an electrophysiological study (EPS) in the Department of Cardiology. Consequently, coronary angiography showed no coronary artery stenosis or anomalies. EPS revealed an arrhythmogenic focus on the latero-anterior apical wall of the left ventricle. Additionally, simultaneous ablation of the focus with radiofrequency current was performed (Figure 2). These procedures were performed on continuous mechanical support. After the procedure, the resolution of arrhythmia and return of sinus rhythm were observed. On the first postoperative day, the patient’s condition deteriorated again, and she developed pulmonary edema. The TTE showed signs of a pericardial tamponade, with LVEF 10% (Figure 3, Videos 1, 2). The patient was once again transferred to the Department of Cardiac Surgery, where the tamponade was decompressed through a median sternotomy, ECMO was recannulated to the central position, and a vent to the left ventricle was inserted. The intra-operative evaluation showed no overt perforation to the free wall of the heart as the cause of the tamponade. The most likely cause of the tamponade was a slight perforation that could not be found. After the procedure, the patient’s condition stabilized, and the sinus rhythm was maintained. In the TTE study, a gradual improvement in left ventricular systolic function was observed, but her chronic acute kidney injury required temporary renal replacement therapy.

Therapy administered in the following days allowed us to terminate the ECMO treatment; however, a new complication appeared – femoral artery embolism – which was treated in the Department of Vascular Surgery. In the following days, the patient required rehabilitation due to bilateral paresis of the lower limbs. On the follow-up cardiac MRI, left ventricular systolic function returned to nearly normal values, with an EF of 53%, and a focus of hypoperfusion within the basal and middle segments of the anterior wall was observed. An ICD for secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD) was implanted. During 1-year follow-up, no episodes of recurrent arrhythmias were noted in the observation of the device at the Outpatient Cardiology Clinic. The patient continued neurological rehabilitation due to a spinal cord stroke, with impaired walking. Eventually, the patient achieved incomplete physical fitness (she uses a rolling walker), but returned to her professional career as a teacher.

Discussion

In the presented case, successful treatment of the patient was possible due to the efficient cooperation of many specialists from various departments and because our patient with VES was admitted directly to a multidisciplinary hospital with the possibility of using ECMO and catheter ablation.

VES is a dramatic clinical scenario, especially for a patient who has not previously been protected by an ICD [1]. Even with successful termination of an arrhythmia, the risk of dying during short-term follow-up is significantly increased, as found in the MADIT-II study [4]. The hazard ratio (HR) for death over the 3 months after VES was 17.8 (95% confidence interval [CI] 8.0 to 39.5,

Treatment in the acute phase of VES requires the fastest possible termination of arrhythmias and stabilization of the cardiovascular system with intravenous antiarrhythmic drugs, preferably amiodarone and beta-blockers, and if they are ineffective, with cardioversion/defibrillation [6]. Verapamil should be used when arrhythmia originates from the His-Purkinje system. In this case, verapamil was not used. Sedation is the key to stabilizing patients with VES, but hemodynamic and/or respiratory instability may limit the use of sedatives such as benzodiazepines or opioid analgesics (eg, morphine and fentanyl). In such cases, mechanical ventilation with orotracheal intubation is absolutely required in refractory forms of VES. In some cases, mechanical ventilation allows for safer administration of drugs that are otherwise not tolerated. Opioid analgesics, benzodiazepines, and propofol are preferred due to their lower negative inotropic effect [7]. The use of beta-blockers in combination with sedation has a positive effect on the release of noradrenaline from the cardiac nerve endings and limiting the arrhythmogenic effect of catecholamines. Sedation, in addition to direct arrhythmia suppression, also allows time to identify reversible causes of VES. If the above treatment is ineffective, electrotherapy is recommended. One way to prevent a recurrence of arrhythmia is to impose a faster rhythm (overdrive stimulation) than the normal ectopic rhythm using an endocavitary electrode for temporary cardiac pacing, or in patients with an implanted pacemaker or ICD, using an external programmer for implantable devices. In the case of VES being resistant to aggressive pharmacological treatment, sedation, electrotherapy, and autonomic modulation can also be used. One of possible techniques which could be used is thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA) [8], especially in combination with left stellate ganglion block (LSGB) [9], and cardiac sympathetic denervation (CSD) [10]. These methods are aimed at reducing adrenergic stimulation by a direct action on the nerve fibers innervating the heart muscle. When conventional treatments for hemodynamically unstable VA fail, use of an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) should be considered, which reduces myocardial ischemia by improving flow through the coronary arteries and at the same time reduces left ventricular afterload and wall stress by facilitating systolic blood outflow. Other circulatory support systems (ECMO, IMPELLA, and a catheter-based miniaturized ventricular assist device) can also be used to improve cardiac and circulatory function in recurrent VT/VF episodes [11]. IABP is quite applicable with a fairly slow and steady rhythm. However, due to the problem with synchronization with the rhythm in ventricular arrhythmias, ECMO or IMPELA could be a better solution. In the case of recurrent monomorphic VT, catheter ablation (CA) is an effective procedure, which focuses on destroying the area of the myocardium responsible for the development or consolidation of arrhythmias by using a catheter inserted into the heart. In the case of continuous VT (lasting >50% of the day and recurring despite the use of antiarrhythmic drugs or various forms of electrotherapy) ablation is the method of choice. Hemodynamic mechanical support during CA has a relevant role to restore end-organ perfusion [12,13]. In the present case, it was indispensable to support the circulation mechanically. The ultimate form of therapy may be heart transplantation. A flowchart with the algorithm for the management of VES is presented in Figure 4.

The reported mortality risk associated with VES is variable in the literature. A meta-analysis of the available evidence reported a 2.5-fold increase in mortality in patients with VES compared with patients with unclustered sustained VA, and a 3.3-fold increase in mortality compared with patients with no sustained VA [14].

In the present case, we used multiple mentioned treatments for VES. However, we did not use the thoracic epidural anesthesia and left stellate ganglion block due to the extremely fast course in the first hours, very quick sedation, mechanical ventilation, and LUCAS based resuscitation, which made it impossible to perform the above procedures.

The presented methods of treatment require a highly specialized center working 24 hours a day. Thanks to a significant commitment of many health professionals, and the efficient coordination of the work of many departments, it was only possible to save the patient’s life without any serious damage to the central nervous system.

Overall, many factors, such as structural heart disease, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, heart failure (HF), electrolyte disturbances, kidney failure, stress, and male sex, may be responsible for VES [1]. This patient had a medical history of eosinophilia of unknown origin. Eosinophilic myocarditis (EM) is a rare disease that is frequently fatal [15,16]. Hoppens et al [15] reported a case of eosinophilic myocarditis with palpitations that evolved into VES and death within 4 days. White blood cell (WBC) count, eosinophil count, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) were in normal, but the autopsy revealed diffuse interstitial infiltrates with extensive involvement of eosinophils and mast cells throughout the left and right ventricular myocardium, consistent with EM. The diagnosis of EM can be difficult and is only made during autopsy [16]. Moreover, peripheral eosinophilia and CRP elevation are absent in more than 20% of cases. There are no proven therapies for EM [17].

The current case is similar to the one described by Hoppens et al [15], in which the patient had ventricular arrhythmia, as described earlier, and eosinophilia of unknown etiology. On admission, there was no evidence of infection or an increased number of eosinophils. Unfortunately, no tissue was collected for histopathological examination during the operation.

Conclusions

A ventricular storm is a serious therapeutic problem. This case report has shown the importance of the rapid diagnosis of VES and emergency management with cardiac defibrillation. Multidisciplinary clinical follow-up is required to investigate and treat any reversible causes and to ensure long-term stabilization of cardiac rhythm. Moreover, it is important that patients with VES are admitted directly to tertiary hospitals with ICCU, as there are able to use ECMO support and perform catheter ablation.

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. The timeline representing procedure history of the patient with ventricular electrical storm (VES) treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management. Table 2.. Laboratory parameters during hospitalization of the patient with ventricular electrical storm (VES) treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management.

Table 2.. Laboratory parameters during hospitalization of the patient with ventricular electrical storm (VES) treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management.

References:

1.. Kowlgi GN, Cha YM, Management of ventricular electrical storm: A contemporary appraisal: Europace, 2020; 22(12); 1768-80

2.. Exner DV, Pinski SL, Wyse DG, Renfroe EG, Electrical storm presages nonsudden death: The antiarrhythmics versus implantable defibrillators (AVID) trial: Circulation, 2001; 103(16); 2066-71

3.. Vergara P, Tung R, Vaseghi M, Brombin C, Successful ventricular tachycardia ablation in patients with electrical storm reduces recurrences and improves survival: Heart Rhythm, 2018; 15(1); 48-55

4.. Sesselberg HW, Moss AJ, McNitt S, Ventricular arrhythmia storms in postinfarction patients with implantable defibrillators for primary prevention indications: A MADIT-II substudy: Heart Rhythm, 2007; 4(11); 1395-402

5.. Hohnloser SH, Al-Khalidi HR, Pratt CM, Electrical storm in patients with an implantable defibrillator: Incidence, features, and preventive therapy: Insights from a randomized trial: Eur Heart J, 2006; 27(24); 3027-32

6.. Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society: Circulation, 2018; 138(13); e210-71

7.. Burjorjee JE, Milne B, Propofol for electrical storm; A case report of cardioversion and suppression of ventricular tachycardia by propofol: Can J Anaesth, 2002; 49(9); 973-77

8.. Bourke T, Vaseghi M, Michowitz Y, Neuraxial modulation for refractory ventricular arrhythmias: Value of thoracic epidural anesthesia and surgical left cardiac sympathetic denervation: Circulation, 2010; 121(21); 2255-62

9.. Meng L, Tseng CH, Shivkumar K, Ajijola O, Efficacy of stellate ganglion blockade in managing electrical storm: A systematic review: JACC Clin Electrophysiol, 2017; 3(9); 942-49

10.. Nademanee K, Taylor R, Bailey WE, Treating electrical storm: Sympathetic blockade versus advanced cardiac life support-guided therapy: Circulation, 2000; 102(7); 742-47

11.. Dallaglio PD, Oyarzabal Rabanal L, Alegre Canals O, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for hemodynamic support of ventricular tachycardia ablation: A 2-center experience: Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed), 2020; 73(3); 264-65

12.. Turagam MK, Vuddanda V, Koerber S, Garg J, Percutaneous ventricular assist device in ventricular tachycardia ablation: A systematic review and meta-analysis: J Interv Card Electrophysiol, 2019; 55; 197-205

13.. Bella PD, Radinovic A, Limite LR, Baratto F, Mechanical circulatory support in the management of life-threatening arrhythmia: EP Europace, 2021; 23(8); 1166-78

14.. Elsokkari I, Saap JL, Electrical storm: Prognosis and management: Prog Cardiovasc Dis, 2021; 66; 70-79

15.. Hoppens KR, Alai HR, Surla J, Fulminant eosinophilic myocarditis and VT storm: JACC Case Rep, 2021; 3(3); 474-78

16.. Kuchynka P, Palecek T, Masek M, Cerny V, Current diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of eosinophilic myocarditis: Biomed Res Int, 2016; 2016; 2829583

17.. Kociol RD, Cooper LT, Fang JC, Recognition and initial management of fulminant myocarditis: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association: Circulation, 2020; 141(6); e69-e92

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. The timeline representing procedure history of the patient with ventricular electrical storm (VES) treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management.

Table 1.. The timeline representing procedure history of the patient with ventricular electrical storm (VES) treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management. Table 2.. Laboratory parameters during hospitalization of the patient with ventricular electrical storm (VES) treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management.

Table 2.. Laboratory parameters during hospitalization of the patient with ventricular electrical storm (VES) treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management. Table 1.. The timeline representing procedure history of the patient with ventricular electrical storm (VES) treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management.

Table 1.. The timeline representing procedure history of the patient with ventricular electrical storm (VES) treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management. Table 2.. Laboratory parameters during hospitalization of the patient with ventricular electrical storm (VES) treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management.

Table 2.. Laboratory parameters during hospitalization of the patient with ventricular electrical storm (VES) treated with emergency cardiac defibrillation followed by multidisciplinary management. In Press

04 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.941835

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943042

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942578

05 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943801

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250