02 October 2022: Articles

Presenting as a Lung Mass in an Immunocompromised Patient

Unusual clinical course, Challenging differential diagnosis

Siddique Qurashi1AEF, Tabinda Saleem1AEF, Iuliia Kovalenko1EF*, Konstantin GolubykhDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.936968

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936968

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Pulmonary cryptococcosis is an uncommon infection mainly affecting immunocompromised individuals. Presentation of cryptococcal disease ranges from asymptomatic pulmonary colonization to severe pneumonia. It can progress to acute respiratory failure and life-threatening meningoencephalitis.

CASE REPORT: A 55-year-old woman with a history of a kidney transplant, on immunosuppressive therapy, presented to the hospital with persistent low-grade fever, headache, weight loss, and fatigue for 2 weeks. On arrival, she was tachycardic, normotensive, and saturating 99% on room air. Her chest X-ray showed right middle lung opacity measuring 1.9×2.8 cm. She was admitted and started on broad-spectrum antibiotics for suspected pneumonia. Her chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed a 3.0×1.7 cm hypo-dense opacity at the right upper lobe. Overnight, she developed a severe headache and neck stiffness. Her serum cryptococcal antigen and cerebrospinal fluid culture results were positive. The patient was started on intravenous liposomal amphotericin B plus flucytosine. A CT-guided lung biopsy was performed to rule out malignancy. Cultures came back positive for Cryptococcus neoformans. She completed a 2-week course of amphotericin and flucytosine and was switched to oral fluconazole to complete an 8-week course.

CONCLUSIONS: Prompt diagnosis and effective management of the cryptococcal disease can decrease morbidity and mortality. Diagnosis requires CT-guided lung biopsy, with culture growing mucoid colonies of Cryptococcus neoformans. Antifungal therapy with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B plus flucytosine is the mainstay of treatment. Clinicians should be aware of the various presentations of pulmonary cryptococcosis, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Keywords: Bacterial Infections and Mycoses, Cryptococcus neoformans, Immunocompromised Host, amphotericin B, Anti-Bacterial Agents, Antifungal Agents, Cryptococcosis, Female, fluconazole, Flucytosine, Headache, Humans, Lung, Middle Aged

Background

Opportunistic invasive fungal infections are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients.

Primary lung infection by

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman with a history of kidney transplant 5 years prior, secondary to polycystic kidney disease leading to end-stage renal disease, currently on immunosuppressive therapy with tacrolimus 0.5 mg twice daily, mycopheno-late 180 mg twice daily and prednisone 5 mg once daily presented with persistent low-grade fever and fatigue over the prior 2 weeks. Her fever was reported to be 36.5–37.7°C at home and associated with headache, which was mostly localized to the frontal area, dull in intensity, with mild neck pain. She also reported poor appetite and a 5 kg weight loss. She denied nausea, vomiting, cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, visual changes, or skin rash. The patient lived on the farm where she had resided for most of her life. Her work included growing and harvesting crops. Her only animal exposure was to dogs and horses. She denied any insect or tick bites or recent travel.

On arrival, she was alert and oriented, with a heart rate of 101 beats/min, temperature 37.8°C, respiratory rate 18/min, blood pressure 123/76 mmHg, with O2 saturation of 99% at room air. Her weight on admission was 52.9 kg (BMI 20.8), which was unchanged from the previous records. She had dry mucus membranes, and her neck was supple, with negative Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs. Her chest was clear to auscultation, with normal heart sounds and no other significant findings.

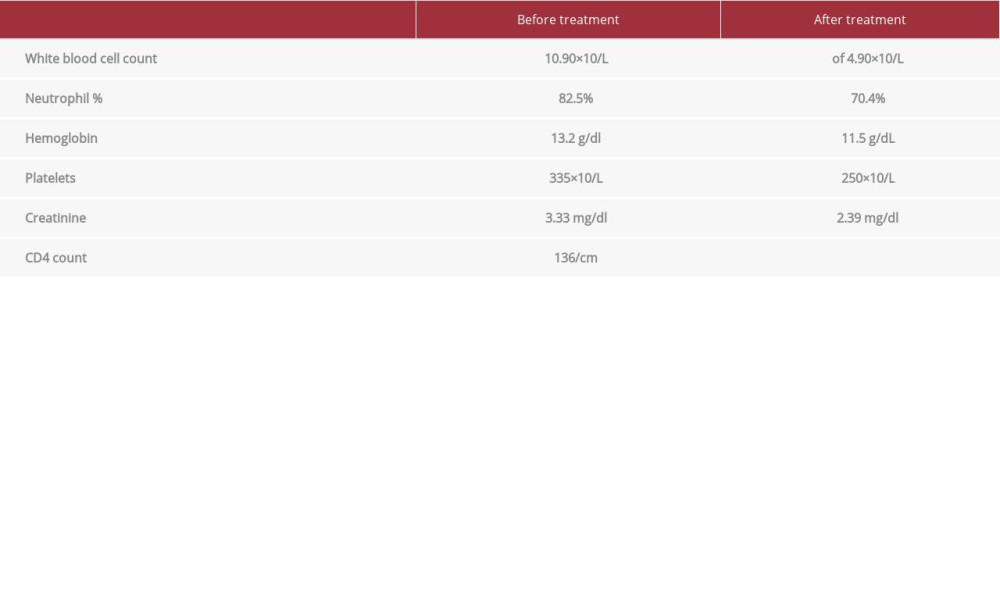

Blood workup on presentation showed a white blood cell count of 10.90×10/L with 82.5% neutrophils, hemoglobin 13.2 g/dl, and platelets 335×10/L. Blood chemistry showed creatinine rise to 3.33 mg/dl from a baseline of 1.3 mg/dl. CD4 count was 136/cm3 (Table 1). An initial chest X-ray showed right mid-lung opacity measuring 1.9×2.8 cm (Figure 1).

A chest CT without contrast was done to further evaluate the lung density. It showed a 3.0×1.7 cm hypo-dense opacity at the right upper lobe (Figure 2).

The patient was admitted to the hospital and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy for probable pneumonia was initiated. Her immunosuppressive therapy was modified, and she was continued only on tacrolimus 0.5 mg and prednisone 5 mg. She was tested for tuberculosis, HIV, histoplasmosis, cytomegalo-virus, Epstein-Barr virus, and

The viral and fungal antigen panel was mostly negative; however, it was positive for serum cryptococcal antigen. Overnight, the patient’s temperature rose to 38.8–39.4°C, and she developed a severe headache and significant neck stiffness. A lumbar puncture was performed, with normal opening pressures. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed nucleated cells of 360/cm3 with differentials showing 60% neutrophils and 23% lymphocytes, proteins 167 mg/dl, and glucose of 15 mg/dl, raising concerns for bacterial meningitis. Bacterial and fungal CSF cultures along with Herpes Simplex virus (HSV) RNA, acid-fast stain, and cytology were sent for analysis. Ceftriaxone and ampicillin were added to the regimen. Later, cryptococcal antigen results were positive in the CSF as well. Bacterial CSF culture, HSV RNA, and CSF cytology did not reveal any abnormalities. The patient was started on 3-phase antifungal therapy, with initial induction of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B 150 mg daily plus flucytosine 3000 mg daily. Blood workup during treatment showed a blood white cell count decrease to normal value of 4.60×10/L with normal neutrophil percentage and kidney function improvement with creatinine of 2.68 mg/dl. Her weight during treatment has increased up to 54.5 kg (BMI of 21.6) during treatment.

Antibiotics were discontinued after the negative CSF culture for bacteria. The patient did not develop signs of raised intracranial pressure. Modified immunosuppressive therapy was continued to prevent immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

Subsequent test results ruled out tuberculosis but raised concerns for a malignant cause of the lung nodule. A CT-guided lung biopsy was performed, and the sample was sent for cytology and culture. In the interim, the patient started to show clinical improvement. She was more active. Her fever and appetite improved. Fine-needle cytology results were negative for malignant cells, but culture results showed mucoid colonies of

Discussion

The incidence of

Cryptococcus infection is caused by an encapsulated heterobasidiomycetous saprophytic fungus that has a worldwide distribution and is endemic in tropical and sub-tropical areas. It is most often seen in patients with T cell-mediated immune deficiencies as found in HIV, leukemia, diabetes, and in patients on corticosteroid therapy or immunosuppressive therapy after a solid organ transplant. Immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, calcineurin inhibitors, and cyclosporine are known to be associated with fungal infections, including cryptococcosis [3–5]. Our patient had been receiving multidrug immunosuppressive therapy including mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus, which put her at high risk of Cryptococcus infection.

Cryptococcus infection can affect the immunocompetent host as well, and can affect virtually any organ of the body, but it primarily affects the lungs and the brain. Unusual presentations such as cryptococcal arthritis, myositis, and choreoretinitis have been described in the literature in immunocompromised patients [3,6]. Humans acquire the infection through inhalation of basidiospore form of the fungus from soil contaminated with bird droppings [7].

There are 2 sub-species of Cryptococcus spp. family that commonly infect humans:

Generally, the primary cryptococcal infection is asymptomatic or presents with nonspecific symptoms. The development of symptoms generally depends upon the inoculum of fungus, the virulence factors of the infecting strain, and the immune status of the person. Most common symptoms, if present, are low-grade fever, fatigue, malaise, productive cough, chest pain, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and weight loss, but severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and life-threatening meningitis can occur, with increased incidence in transplant recipients [8]. Immunocompromised patients often have a subtle clinical course with nonspecific symptoms, such as our patient, which makes diagnosis particularly challenging.

Postmortem studies in immunocompetent hosts have demonstrated

The diagnosis of cryptococcal infection is usually made with serology, radiology, and fungal culture. Often, the cryptococcal mass is identified as an incidental finding on a chest X-ray. On a CT scan chest, the cryptococcal mass most commonly appears as a well-defined, solitary, non-calcified pleural-based nodule, but there can be multiple masses. Our patient’s CT scan displayed a typical cryptococcal mass that was well-circumscribed and adjacent to the pleura, with no calcified foci.

Serum cryptococcal antigen is a sensitive tool in immunocom-promised patients and titers often reflect the severity of disease, but ultimate diagnosis is usually by CT-guided biopsy and fungus culture. On culture,

Optimal treatment for cryptococcal infection is uncertain as very little data is available. According to the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Cryptococcal Disease, last updated by the Infectious Diseases Society of America in 2010, different treatment strategies are used for immunocompetent versus immunocompromised patients [11].

For patients with isolated lung mass with mild to moderate symptoms, in the absence of disease dissemination, fluconazole 400 mg per day orally is given for 6–12 months. If fluconazole is not available or not tolerated, alternative therapy with itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, or isauconazole can be considered, although minimal data is available for the latter 2 agents. However, if there is no response to the anti-fungal therapy or there is the persistence of radiographic abnormalities, surgery can be considered.

Patients with severe pulmonary disease (eg, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates, multiple nodules, or ARDS), those with disseminated disease at more than 2 sites (meningoencephalitis), or serum cryptococcal antigen titer >1: 512 should be managed with 3-phase therapy along with management of intracranial pressure (ICP) and reduction in immunosuppressive therapy. Steroids can also help with the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Induction therapy is preferred, with a combination of intravenous amphotericin B (3–4 mg/kg/day) plus flucytosine for 2–4 weeks, depending on the patient’s response and clinical improvement. Liposomal amphotericin B is recommended in patients with renal impairment. Following induction, consolidation therapy with oral fluconazole (6–12 mg/kg/day) is recommended for 8 weeks, with maintenance azole therapy lasting for 1 year [12]. The immunosuppressant regimen often needs to be adjusted in patients with acute kidney injury related to amphotericin B. Modifying the dose of the immunosuppressive drugs can also prevent immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, which often presents with worsening of the pulmonary or neurological symptoms, making it difficult to differentiate between the progression of primary infection or body autoimmune response [13]. Our patient required discontinuation of mycophenolate mofetil along with tacrolimus dose adjustment for both acute kidney injury and immune reconstitution syndrome prevention.

Control of intracranial pressure in patients with meningoencephalitis is one of the most critical factors affecting the outcome. Therapeutic lumbar drainage is recommended, with no proven benefits of glucocorticoids [14]. However, our patient was already on prednisone as part of her cancer regimen. Her opening pressure remained low during the lumbar puncture. In addition, she did not develop any signs of raised intracranial pressure, favoring the benefits of steroids.

Cryptococcal infections mortality rate in transplant patients is reported to range from 15% to 20% and approaches 40% in patients with CNS involvement. The latter justifies the need of raising physician awareness to promote timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment [13,15,16].

Conclusions

Diagnosis of cryptococcosis remain challenging in the United States due to disease rarity and lack of specificity of clinical presentation. Immunocompromised patients can have subtle clinical course and unusual disease presentations, including lung granulomas formation. Timely diagnosis is crucial in mortality reduction as patients usually have a good clinical response to the antifungal therapy when started early. Suspicion for cryptococcosis should remain particularly high in immunocompromised patients, who also require an individualized treatment approach. All the above highlights the importance of physician awareness of the increased incidence of cryptococcal infections in this patient population.

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Laboratory values.

References:

1.. : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [cited 2022 Mar24]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/cryptococcosis-neoformans/statistics.html

2.. Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: An update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992–2000: Clin Infect Dis, 2003; 36(6); 789-94

3.. Garau M, del Palacio A, [Cryptococcus neoformans arthritis in a renal transplant recipient]: Rev Iberoam Micol, 2002; 19(3); 186-89 [in Spanish]

4.. Gras J, Tamzali Y, Denis B: Med Mycol Case Rep, 2021; 32; 84-87

5.. Singh N, Alexander BD, Lortholary O: J Infect Dis, 2007; 195(5); 756-64

6.. Husain S, Wagener MM, Singh N: Emerg Infect Dis, 2001; 7(3); 375-81

7.. Emmons CW: Am J Hyg, 1955; 62(3); 227-32

8.. Vilchez RA, Linden P, Lacomis J, Acute respiratory failure associated with pulmonary cryptococcosis in non-aids patients: Chest, 2001; 119(6); 1865-69

9.. Baker RD, Haugen RK, Tissue changes and tissue diagnosis in cryptococcosis; A study of 26 cases: Am J Clin Pathol, 1955; 25(1); 14-24

10.. Shimizu H, Hara S, Nishioka H, Disseminated cryptococcosis with granuloma formation in idiopathic CD4 lymphocytopenia: J Infect Chemother, 2020; 26(2); 257-60

11.. , Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: Recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America[cited 2019 July 10] https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/Adult_OI.pdf

12.. Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: Clin Infect Dis, 2010; 50(3); 291-322

13.. Singh N, Perfect JR, Immune reconstitution syndrome associated with opportunistic mycoses: Lancet Infect Dis, 2007; 7(6); 395-401

14.. Park MK, Hospenthal DR, Bennett JE, Treatment of hydrocephalus secondary to cryptococcal meningitis by use of shunting: Clin Infect Dis, 1999; 28(3); 629-33

15.. John GT, Mathew M, Snehalatha E, Cryptococcosis in renal allograft recipients: Transplantation, 1994; 58(7); 855-56

16.. Alexander BD, Cryptococcosis after solid organ transplantation: Transpl Infect Dis, 2005; 7(1); 1-3

Figures

In Press

14 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942770

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943214

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943010

16 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943687

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250