05 August 2023: Articles

Effective Treatment of Acute Tricyclic Antidepressant Poisoning with Cardiogenic Shock and Severe Rhabdomyolysis Using ECMO and CytoSorb Adsorber

Management of emergency care, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Zakaria ZitouneDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.939884

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e939884

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) drugs are a common cause of fatal poisoning because of their cardiotoxic and arrhythmogenic effects. Classic supportive management includes sodium bicarbonate, gastrointestinal chelating agents, and vasopressors. Recently, intravenous lipid emulsion (supported by a low evidence level) has also been used.

CASE REPORT: We report the case of a 55-year-old woman admitted to our Intensive Care Unit (ICU) with acute imipramine self-poisoning. She arrived at the emergency department 7 hours after imipramine ingestion; she had severe rhabdomyolysis upon admission, with creatine phosphokinase levels at about 52 500 IU/L (normal, <200 IU/L). She quickly developed cardiogenic shock and malign arrhythmia requiring veno-arterial extra corporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO). Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) with CytoSorb® (CytoSorbents, Monmouth Junction, New York, United Sates of America) was started 19 hours after admission. We performed serial blood measurements of imipramine and its active metabolite desipramine as well as viewing the levels on the CRRT-circuit monitor. Cardiac function improved and ECMO was explanted after 4 days. She also had severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, which resolved spontaneously. The neurologic outcome was favorable despite early myoclonus. The patient regained consciousness on the fifth day. Her clinical evolution was marked by acute ischemia of the lower left limb due to the arterial ECMO cannula.

CONCLUSIONS: These measurements document the efficacy of the CytoSorb® adsorber in removing a lipophilic drug from a patient's bloodstream. To our knowledge, this is the first published case of CytoSorb® extracorporeal blood purification therapy for acute TCA poisoning.

Keywords: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, Antidepressive Agents, Tricyclic, Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy, Poisoning, Female, Humans, Middle Aged, Shock, Cardiogenic, imipramine

Background

Tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) drugs were first commercialized in the 1950s. Although they are used less frequently since the development of other antidepressant classes (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) they remain a common cause of fatal drug poisoning because they have more toxic effects than newer antidepressants. In the case of overdose, TCAs have severe cardiotoxic (arrhythmogenic) and neurotoxic effects. Cardiac effects are mediated by their action on fast sodium channels in the cardiac conduction pathway and myocardium [1].

TCAs are lipophilic and are primarily metabolized by the liver [2]. Because of their lipophilic nature, they tend to accumulate in adipose tissue and thus have a large volume of distribution [2]. They yield many pharmacologically active metabolites, and the majority of the drug is excreted by the kidneys after metabolization. Regarding intravenous lipid emulsion (ILE), a number of articles have compiled and evaluated the use of lipids in human clinical situations, all coming to similar conclusions [2]. For both local anesthetic and nonlocal anesthetic overdoses, only low-level evidence, largely from animal models and case reports, exists in support of using ILE [2]. The therapeutic total concentration of imipramine and desipramine are around 175–300 µg/L in total [3]. Toxic concentrations are above 500 µg/L, with cardiac manifestations starting around 400 µg/L. Lethal concentrations are above 1000 µg/L The therapeutic range is therefore narrow: usual oral doses for tricyclic anti-depressants are around 100 to 200 mg/day, while lethal doses are above 1 gram [3]. We report the case of a woman with acute imipramine self-poisoning [4].

Case Report

A 55-year-old woman was admitted to our ICU for acute imipramine self-poisoning. She was unconscious (Glasgow Coma Scale of 6/15) upon arrival at the Emergency Medical Services (about 7 hours after ingestion) and was intubated on site. Cardiopulmonary auscultation showed reduced cardiac sounds and basal crepitation suggestive of lung edema. Neurologically, she had no sign of lateralization. There was no peristaltism on abdominal auscultation. She received a gastric lavage with activated charcoal but without any positive effect due to the late arrival of the patient. Very quickly, she went into cardiogenic shock. She received 9 liters of crystalloid fluids in the first 12 hours. Echocardiography and pulse contour continuous cardiac output (PiCCO) monitoring were used to assess her cardiac function. The ejection fraction was 5–10% (cardiodepression) under 2 mcg/kg/min of noradrenaline, 15 mcg/kg/min of dobutamine, and 1 mcg/kg/min of adrenaline. The electrocardiogram (ECG) was very enlarged, with a QRS duration >100 milliseconds; therefore, she received, intravenously, 200 milliequivalents of bicarbonate, without any positive results. Further, she had ventricular tachycardia, torsade de pointes, and ventricular fibrillation (see Figure 1). Her last measurement of CO with the PiCCO was 0.3 L/min. The acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score was 40, with an expected mortality of 91%. Urgently, veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) was initiated, under a right femoral access in the left groin (flow of 3.5 L/min-gas flow of 6). She improved substantially, until she could be weaned off of all the inotropes except a small dose of noradrenaline of about 0.4 mcg/kg/min. Laboratory values upon admission revealed creatine phosphokinase at about 52 500 IU/L (normal, <200 UI/L), aspartate aminotransferase at 4254 U/L (normal, <35 U/L), alanine aminotransferase at 3452 U/L (normal, <35 U/L), urea at 175 mg/dL (normal, 5–20 mg4L), creatinine at 4.5 mg/dL (normal, 0.5–1 mg/dL), sodium at 141 mEq/L (normal, 135–145 mEq/L), potassium at 5.5 mEq/L (normal, 3.5–5 mEq/L), chloride at 94 mEq/L (normal, 96–106 mEq/L), and magnesium at 2.1 mg/dL (normal, 1.5–2.4 mg/dL). Arterial blood gas results showed a pH of 7.03 (normal, 7.35–7.45), a pCO2 of 34 mmHg (normal, 35–45 mmHg), a pO2 of 65 mmHg (normal, 75–100 mmHg) under 100% oxygen fraction with a positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 10, a bicarbonate level of 12 mmol/L (normal, 23–28 mmol/L), and a lactate of 17 mmol/L (normal, <2.0 mmol/L). The c-reactive protein level was 35 mg/Liter (normal, <10 mg/L).

The initial level of imipramine was 1174 µg/L, and desipramine was 965 µg/L, which are clearly above lethal concentrations. We did start continuous veno-venous hemofiltration (CVVH) due to the occurrence of oliguria and severe rhabdomyolysis shortly thereafter. The CytoSorb was inserted 19 hours after admission and thus approximately 24 hours after the ingestion. The patient required 3 CytoSorb adsorbers, which were changed every 24 hours. After 48 hours, she was still in a deep coma without sedation (Glasgow Coma Scale of 3/15) and with myoclonus potentially due to hypoxic brain injuries. The prognosis was very poor. However, the VA-ECMO was weaned after 4 days, and after 5 days, she woke up completely with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15/15 but still had severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and acute kidney injury.

In our case, blood levels of imipramine and desipramine were measured every 6 hours during the CytoSorb® adsorber treatment. Measurements were done on arterial blood as well as on the CVVH circuit (pre- and post-adsorber) as shown in Figures 2 and 3. On average, post-filter imipramine levels were 45% lower than pre-filter levels and post-filter desipramine levels were 32% lower than pre-filter levels. The ARDS resolved spontaneously over the following days. A second cardiac echo-cardiography was done prior to the removal of the VA-ECMO, and had completely normalized. The patient’s condition was complicated by acute ischemia of the lower left limb due to the arterial ECMO cannula, despite the use of a back-flow cannula. The ischemia was treated by surgical thrombectomy and fasciotomy of the calf. The fasciotomy was closed at day 15. In the end, the patient lost 60% of the muscles in her left calf but was able to walk after rehabilitation. She then improved very slowly but soon after developed right lower pneumonia retrospectively due to influenza infection treated by oseltamivir. Serial measurements of rhabdomyolysis markers are useful to unravel new ischemia and monitor the patient’s condition to determine when CVVH can be stopped. CVVH was stopped at day 18. She was discharged 4 weeks after admission to the ward.

Discussion

TCA intoxication remains a common occurrence, but effective treatment options remain scarce. Classic management of TCA intoxication is purely supportive as reviewed below. Recently, lipid emulsion therapy has been increasingly used in the treatment of lipophilic drug intoxications, but evidence supporting its use remains scarce for non-local anesthetic toxicity.

Sodium bicarbonate is the most widely used treatment for TCA poisoning. TCAs and other drugs like flecainide, cocaine, lamotrigine, diphenhydramine, and citalopram induce QRS widening and malign arrhythmia by blockade of cardiac fast sodium channels. QRS duration over 100 milliseconds is often used as the threshold for bicarbonate treatment [5].

It is not yet fully understood whether the antiarrhythmic properties of sodium bicarbonate are mediated by an increase in pH or by an increase in sodium concentration. There are in vitro and in vivo studies supporting both hypotheses. The answer probably depends on the drug that is responsible for the cardiotoxicity [6].

If hypotension is refractory to fluid resuscitation and sodium bicarbonate, alpha-agonists like noradrenaline are the treatment of choice to counteract the alpha-antagonist properties of TCAs.

Hypertonic saline has been used as an alternative to sodium bicarbonate, but it is not as well-documented and most studies have not demonstrated an antiarrhythmic effect.

Activated charcoal has been the most widely used adsorbent material in medicine for many years [7]. It is used in almost all acute intoxications. Diosmectite is another adsorbent material used in drug poisoning. A recent in vitro study found imipramine to be absorbed significantly better by diosmectite compared with activated charcoal [8].

In the context of TCA intoxication, seizures are likely caused by GABA-A receptor inhibition. GABA-agonists like benzodiazepines are the logical treatment of choice. In case of seizures refractory to benzodiazepines, barbiturates may be used.

ILE involves the administration of a 20% lipid emulsion. The most widely accepted theory describing its mechanism of action purports that lipid emulsion pulls the liposoluble drugs from the tissues and reduces their volume of distribution. The first 2 cases of ILE use in humans were published in 2006 in patients with cardiac arrest related to local anesthetic toxicity [9,10]. ILE had also previously been shown to decrease mortality in animal models of bupivacaïne overdose.

Subsequently, ILE has been used to treat intoxications with many other liposoluble drugs (eg calcium channel antagonists, beta blockers, insecticides, and TCAs). However a recent systematic review of the effect of ILE in non-local anesthetic toxicity concluded that evidence remains low to very low in this setting [11]. In an animal model of TCA toxicity in swine, ILE did not improve hypotension compared with sodium bicarbonate [12]. Similarly, a human cohort study including patients poisoned with tricyclics found no clinically significant improvement after ILE administration [13]. TCAs are lipophilic and considered non-dialysable. Nonetheless, dialysis continues to be used in TCA poisoning, as reported by a 2016 retrospective study of patients receiving dialysis for drug poisoning in Canada, Denmark, the United States of America, and the United Kingdom [14]. There are several hypotheses to explain why dialysis is still used, like a high absolute number of exposures to these toxins, exposure to a possible co-ingestant, or use for purposes other than intoxication, like concomitant acute kidney injury [15]. In its 2014 guidelines, the extracorporeal treatment in poisoning (EXTRIP) workgroup recommends not using extracorporeal removal for TCA poisoning [16]. We report the use of a new and innovative approach to treat TCA intoxication. Extracorporeal removal has the potential of changing the management of TCA intoxication by tackling the problem at the source. Serial pre- and post-filter measurements clearly show the efficacy of the CytoSorb® adsorber in removing imipramine, as well as its main metabolite desipramine, from the circulation. Desipramine is an active metabolite of imipramine; 80% of imipramine is excreted by the kidneys in the form of inactive metabolites. In healthy individuals, elimination half-life of TCAs is about 1 day and clearance is dependent primarily on hepatic cytochrome P450 metabolization [17]. In our case, the CytoSorb® adsorber was started with some delay after admission. It is possible that early initiation of extracorporeal removal could prevent the distribution and accumulation of lipophilic drugs in adipose tissue, and thus markedly shorten and decrease the severity of cardiac TCA toxicity.

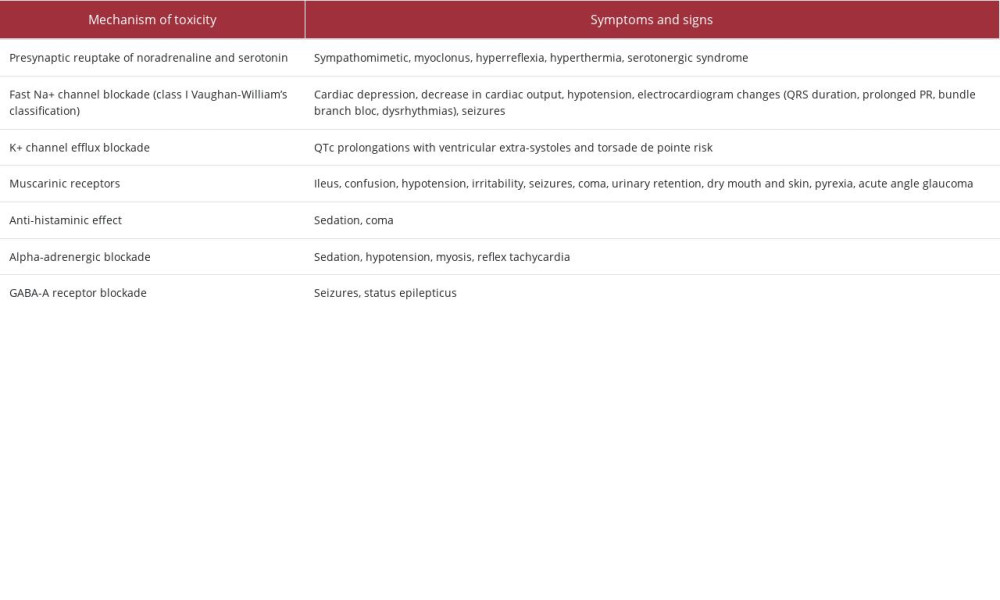

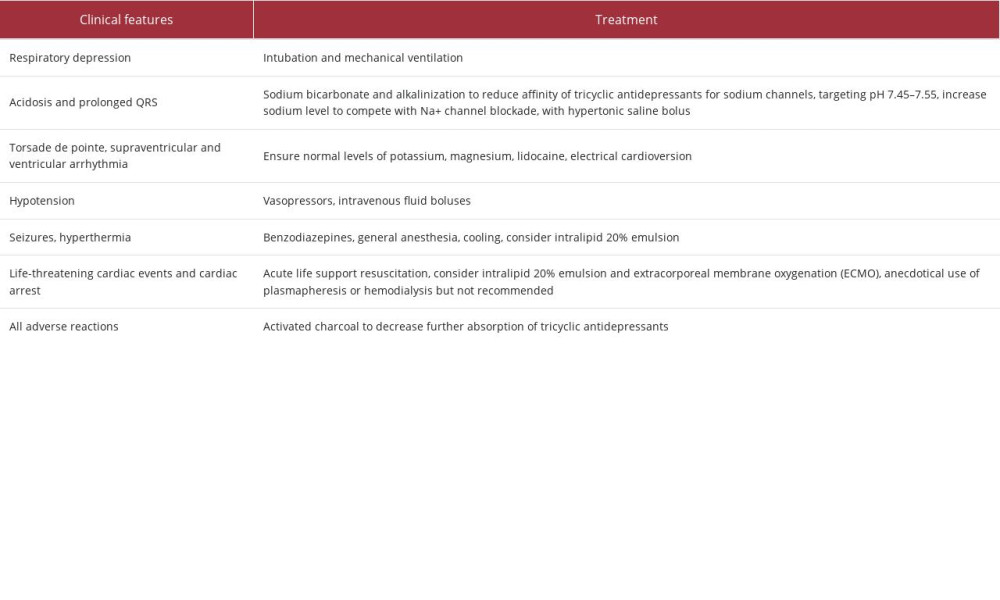

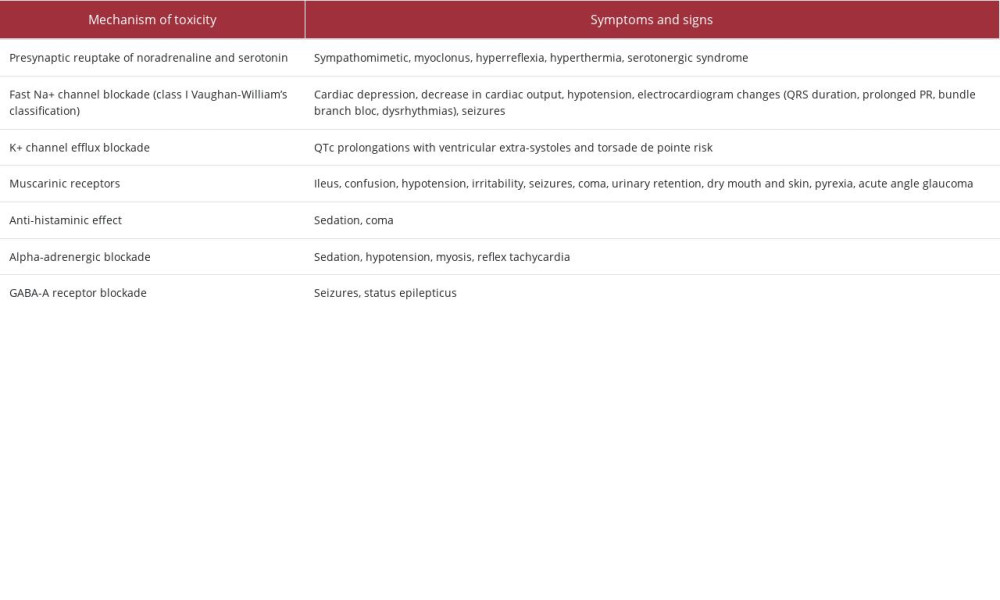

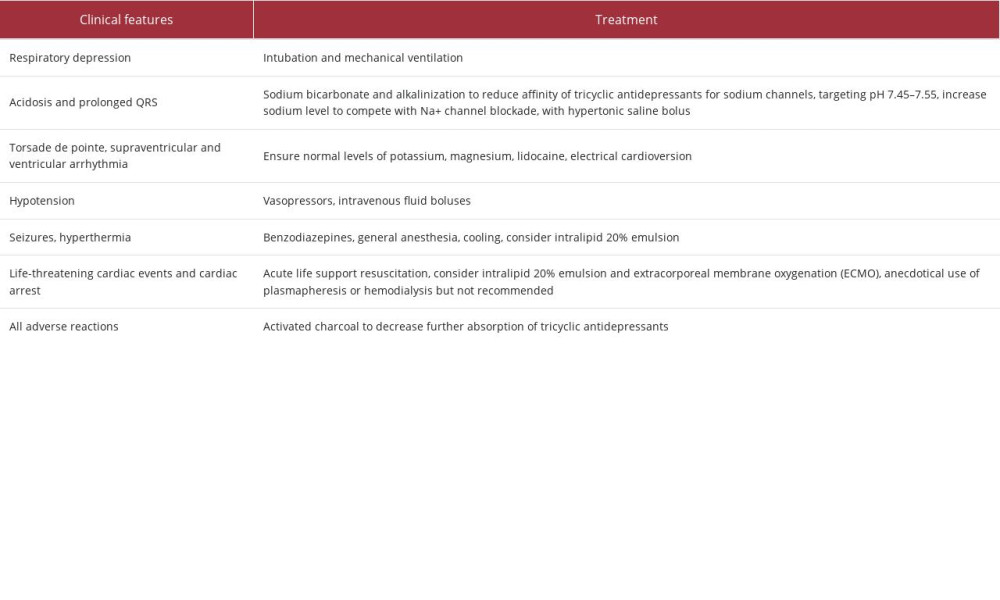

The CytoSorb® hemoperfusion cartridge was initially developed to remove cytokines and endotoxins from the blood. It was intended for patients with an acute inflammatory state such as septic shock, infection, pancreatitis, trauma, and high-risk interventions (eg, open heart surgery). The CytoSorb® cartridge is connected to an extracorporeal circuit like hemodialysis, continuous renal replacement therapy, or ECMO. It contains porous polymer beads and works by adsorbing hydrophobic substances in the 5–60 kilodalton molecular weight range. After the early-development stages of these adsorbent hemoperfusion cartridges, their use in drug intoxication was envisioned. In vitro studies show some promise for removal of many drugs, especially lipophilic drugs not removed by hemodialysis [18]. As CytoSorb® was developed primarily for septic shock patients, most experimental and clinical data has focused on the adsorption of antibiotics [19–21]. Schroeder et al published the only case report of CytoSorb® for intoxication from a drug other than antibiotics. They report a patient with massive venlafaxine intoxication (18 grams) with cardiogenic shock being treated by ILE, ECMO, and CytoSorb®. Plasma levels of venlafaxine decreased during treatment but no pre- and post-filter measurements evaluated the efficacy of CytoSorb® [22]. Adsorbent hemoperfusion devices hold promise for the removal of toxic substances. There is promising in vitro data to support their use but further clinical studies are necessary to confirm patient benefit. Tables 1 and 2 show current TCA treatment options and mechanisms of toxicity. Thyrotoxicosis-induced cardiomyopathy is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that occurs in less than 1% of thyrotoxic individuals [23]. In this case, the use of VA-ECMO can be considered as a “bridge” to recovery of cardiac function after restoration of a euthyroid state [23]. This is somewhat similar to our case, where VA-ECMO was used as a bridge to allow significant reduction of imipramine and desipramine by CytoSorb.

Tricyclic agents can cause more significant adverse reactions, have lower toxicity thresholds, and have a narrower therapeutic range than other classes of antidepressants. For these reasons, they are a second-line treatment for mood disorders and have been replaced by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors due to their better safety profile [24]. As for other antidepressant agents, the first 28 days of treatment and withdrawal are a particular period of risk for suicide and should require more attention from the physician regarding any life stress, particularly in individuals under 25 years old [25]. Several cases of antidepressant abuse have been reported, such as taking large doses to produce euphoria, dissociative effects, and more sociability; however, the extent of abuse is unknown. Drug abusers and prisoners are particularly at risk [26]. These products are considered easily accessible, mainly through medical prescription, but a fifth of current abusers report selling or distributing them [27]. In some countries, tricyclic intoxications constitute up to 10% of drug-related deaths, of which at least 20% are accidental [28].

Conclusions

We have reported a case of severe TCA poisoning treated with the CytoSorb® adsorber, with blood measurements demonstrating the ability of the filter to absorb imipramine and desipramine. Further studies are necessary to evaluate the clinical benefit of this new treatment.

Figures

References:

1.. Khalid MM, Waseem M, Tricyclic antidepressant toxicity. 2022 Aug 7.: StatPearls [Internet]. Jan, 2023, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing

2.. Fettiplace MR, Weinberg G, Past, present, and future of lipid resuscitation therapy: JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2015; 39(1 Suppl.); 72S-83S

3.. Abdollahi M, Mostafalou S, Tricyclic Antidepressants: Encyclopedia of toxicology, 2014; 838-45, Oxford, UK, Academic Press

4.. De Bels D, Redant S, Kugener L: Perfusion, 2020; 35(1 Suppl.); 93-282

5.. Boehnert MT, Lovejoy FH, Value of the QRS duration versus the serum drug level in predicting seizures and ventricular arrhythmias after an acute overdose of tricyclic antidepressants: N Engl J Med, 1985; 313; 474-79

6.. Bruccoleri RE, Burns MM, A literature review of the use of sodium bicarbonate for the treatment of QRS widening: J Med Toxicol, 2016; 12; 121-29

7.. Lucas GH, Henderson VE, The value of medicinal charcoal (Carbo Medicinalis C.F.) in medicine: Can Med Assoc J, 1933; 29; 22-23

8.. Mináriková M, Fojtikova V, Vyskočilová E, The capacity and effectiveness of diosmectite and charcoal in trapping the compounds causing the most frequent intoxications in acute medicine: A comparative study: Environ Toxicol Pharmacol, 2017; 52; 214-20

9.. Litz RJ, Popp M, Stehr SN, Koch T, Successful resuscitation of a patient with ropivacaine-induced asystole after axillary plexus block using lipid infusion: Anaesthesia, 2006; 61; 800-1

10.. Rosenblatt MA, Abel M, Fischer GW, Successful use of a 20% lipid emulsion to resuscitate a patient after a presumed bupivacaine-related cardiac arrest: Anesthesiology, 2006; 105; 217-18

11.. Levine M, Hoffman RS, Lavergne V, Systematic review of the effect of intravenous lipid emulsion therapy for non-local anesthetics toxicity: Clin Toxicol, 2016; 54; 194-221

12.. Varney SM, Bebarta VS, Vargas TE, Intravenous lipid emulsion therapy does not improve hypotension compared to sodium bicarbonate for tricyclic antidepressant toxicity: A randomized, controlled pilot study in a swine model: Acad Emerg Med, 2014; 21; 1212-19

13.. Mithani S, Dong K, Wilmott A, A cohort study of unstable overdose patients treated with intravenous lipid emulsion therapy: CJEM, 2017; 19(4); 256-64

14.. Ghannoum M, Lavergne V, Gosselin S, Practice trends in the use of extracorporeal treatments for poisoning in four countries: Semin Dial, 2016; 29; 71-80

15.. Lavergne V, Hoffman RS, Mowry JB, Why are we still dialyzing overdoses to tricyclic antidepressants? A subanalysis of the NPDS database: Semin Dial, 2016; 29; 403-9

16.. Yates C, Galvao T, Sowinski KM, Extracorporeal treatment for tricyclic antidepressant poisoning: Recommendations from the EXTRIP Workgroup: Semin Dial, 2014; 27; 381-89

17.. Rudorfer MV, Potter WZ, Metabolism of tricyclic antidepressants: Cell Mol Neurobiol, 1999; 19; 373-409

18.. Reiter K, Bordoni V, Dall’Olio G, In vitro removal of therapeutic drugs with a novel adsorbent system: Blood Purif, 2002; 20; 380-88

19.. Morris C, Gray L, Giovannelli M, Early report: The use of Cytosorb™ haemabsorption column as an adjunct in managing severe sepsis: Initial experiences, review and recommendations: Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2015; 16; 257-64

20.. König C, Röhr AC, Frey OR, In vitro removal of anti-infective agents by a novel cytokine adsorbent system: Int J Artif Organs, 2019; 42; 57-64

21.. Poli EC, Simoni C, André P, Clindamycin clearance during CytoSorb® hemoadsorption: A case report and pharmacokinetic study: Int J Artif Organs, 2019; 42; 258-62

22.. Schroeder I, Zoller M, Angstwurm M: Int J Artif Organs, 2017; 40; 358-60

23.. Lorlowhakarn K, Kitphati S, Songngerndee V, Thyrotoxicosis-induced cardiomyopathy complicated by refractory cardiogenic shock rescued by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: Am J Case Rep, 2022; 23; e935029

24.. Moraczewski J, Aedma KK, Tricyclic antidepressants. [Updated 2022 Nov 21].: StatPearls [Internet]. Jan, 2023, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557791/?report=classic

25.. Coupland C, Hill T, Morriss R, Antidepressant use and risk of suicide and attempted suicide or self harm in people aged 20 to 64: Cohort study using a primary care database.: BMJ., 2015; 350; h517

26.. Evans EA, Sullivan MA, Abuse and misuse of antidepressants.: Subst Abuse Rehabil, 2014; 5; 107-20

27.. Darke S, Ross J, The use of antidepressants among injecting drug users in Sydney, Australia: Addiction, 2000; 95(3); 407-17

28.. Cheeta S, Schifano F, Oyefeso A, Antidepressant-related deaths and antidepressant prescriptions in England and Wales, 1998–2000: Br J Psychiatry, 2004; 184; 41-47

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Mechanism of toxicity and symptoms associated with tricyclic antidepressant poisoning.

Table 1.. Mechanism of toxicity and symptoms associated with tricyclic antidepressant poisoning. Table 2.. Clinical features and treatment options for tricyclic antidepressant poisoning.

Table 2.. Clinical features and treatment options for tricyclic antidepressant poisoning. Table 1.. Mechanism of toxicity and symptoms associated with tricyclic antidepressant poisoning.

Table 1.. Mechanism of toxicity and symptoms associated with tricyclic antidepressant poisoning. Table 2.. Clinical features and treatment options for tricyclic antidepressant poisoning.

Table 2.. Clinical features and treatment options for tricyclic antidepressant poisoning. In Press

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942853

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942660

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943174

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943136

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250