26 July 2023: Articles

Recurrent Syncope Episodes during Spinal Anesthesia for Perianal Abscess Drainage: A Case Report Emphasizing Pain as a Trigger

Unusual clinical course, Challenging differential diagnosis, Diagnostic / therapeutic accidents, Management of emergency care, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Junyang Ma1E, Xiaoxia Tian1B, Liqin DengDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.940391

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e940391

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Vasovagal syncope is a loss of consciousness caused by decreased arterial pressure and cerebral blood flow. The characteristic features of vasovagal syncope include cardiovascular inhibition caused by neural reflexes, accompanied by vasodilation and bradycardia. To date, there is little literature to report several episodes of syncope under spinal anesthesia during the perioperative period for drainage of an anal abscess. The purpose of this article is to alert clinical practitioners to the early identification of the underlying causes of vasovagal syncope and to facilitate timely and effective management strategies.

CASE REPORT: We present the case of a 44-year-old man with a perianal abscess who was scheduled for an incision and drainage procedure for the abscess under spinal anesthesia. Preoperative assessment revealed no history of cardiac disease, neurological disorders, or drug allergies. During the perioperative period, the patient experienced 3 episodes of syncope: 1 episode during puncture of spinal anesthesia, and the others at 6.5 h and 8.5 h after the procedure. The patient was discharged 4 days later, and a 30-day postoperative follow-up showed good recovery, without any episodes of syncope.

CONCLUSIONS: We described a case of 3 episodes of vasovagal syncope occurring in a patient during the perioperative period of drainage of perianal abscess under spinal anesthesia. Pain may have been the main cause of vasovagal syncope in this patient. To avoid vasovagal syncope, it is best for anesthesiologists to choose the lateral position to perform spinal anesthesia and to provide good perioperative pain management for these patients.

Keywords: Abscess, Anesthesia, Spinal, Syncope, Vasovagal, Perianal Glands, Male, Humans, Adult, Syncope, Drainage, Anus Diseases, Pain

Background

Perianal abscess is the most common type of abscess in the anal and rectal area. It is localized in the perianal space and often causes severe pain around the anus [1]. About 90% of anal and rectal abscesses are a result of a nonspecific blockage leading to infection of the rectal and anal glands [1,2]. Perianal abscess can lead to various complications, including sepsis, recurrent abscesses, fistula formation, and fecal incontinence [3]. For a perianal abscess, timely incision and drainage are the best treatment methods, usually performed under local or spinal anesthesia [4,5].

Severe pain caused by a perianal abscess can stimulate the sacral nerve plexus to induce a stronger vagal reflex and syncope [6,7]. Syncope is characterized by an abrupt, transient, and complete loss of consciousness, associated with an inability to maintain postural tone, and a rapid and spontaneous recovery [8]. Syncope is believed to be caused by cerebral hypoperfusion. The pathogenesis of syncope is vast and includes reflex syncope, orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac syncope [9]. Vasovagal syncope is the most common form of reflex syncope [10]. Its characteristic features include bradycardia and vasodilation, due to reflex cardiovascular depression [11]. Vasovagal syncope can occur in conditions of reduced blood volume, positional changes, and compression of the inferior vena cava and during spinal anesthesia in pregnancy [11].

We conducted a review of the PubMed database, including studies from 2000 to 2022, and analyzed 8 relevant cases in order to enhance awareness among clinicians regarding this rare condition. We did not find literature reporting several continuous episodes of syncope during the perioperative period of drainage of an anal abscess. This report is of a 44-year-old man with 3 episodes of syncope due to a vasovagal response during administration of spinal anesthesia and after a procedure for drainage of an anal abscess. Our goal is to assist anesthesiologists and surgeons in finding the cause of the vasovagal syncope, choosing the suitable anesthesia protocol, and avoiding the episode of vasovagal syncope in patients undergoing drainage of a perianal abscess. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 44-year-old, previously healthy man (175 cm, 76 kg) visited our hospital with concerns of anal pain that had started 3 days earlier. Upon visual examination, swelling and redness were observed on his left buttock. Digital examination revealed a swelling of the left side of the anal canal. Digital rectal examination showed the anal sphincter was moderately tight, and a hard area could be palpated on the left posterior wall of the rectum, which was positive for tenderness. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed infectious lesions and abscess formation in the rear of the lower rectum and perianal area, and an electronic colonoscopy revealed rectal polyps. Laboratory blood test results showed an elevated white blood cell count (10.82×109/L) and neutrophil count (7.05×109/L). An electrocardiogram (ECG) returned normal findings. The patient’s vital signs at presentation were temperature, 36.4°C; pulse, 60 beats/min; blood pressure, 106/75 mmHg; and respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min. He was admitted to the hospital with a perianal abscess, which was evaluated in the Outpatient Department, and was scheduled for elective surgery. At the pre-anesthesia visit, the patient’s serum electrolytes were in the normal range, and the serum glucose level was 4.54 mmol/L. The patient denied a history of hypertension, hypotension, diabetes, nervous system disease, and drug allergy. The patient agreed to spinal anesthesia and reported he did not have a needle phobia.

The patient had not eaten for 24 h prior to surgery. A total of 500 mL of 5% glucose was administered intravenously at 8 a.m. on the day of surgery. The patient arrived in the operating room at 6: 50 p.m. ECG, oxygen saturation, venous channel, and noninvasive blood pressure monitoring every 5 min were initiated, indicating a heart rate of 61 beats/min and blood pressure 90/60 mmHg. In a sitting position, his visual analog scale (VAS) score was 4, and saddle block anesthesia was administered at the L4-L5 interspace via spinal puncture using the subarachnoid block technique. After strict asepsis, 2 mL of 2% lidocaine was infiltrated to achieve local anesthesia. Spinal anesthesia via the midline approach was started 1 min later. During spinal puncture with a 25 G syringe needle under guidance of a 20 G syringe needle, the patient reported dizziness and visual blurring and became pale and diaphoretic, with transient loss of consciousness and dystonia, which was followed by limb convulsions for 5 s. We let the patient lie supine by immediately pulling out the needle, and administered 6 mg ephedrine intravenously. The vital signs monitor indicated a heart rate of 52 beats/min, and noninvasive blood pressure measurements taken every 5 min revealed no systolic blood pressure readings of <90 mmHg. The patient was immediately given 20 mL of 50% glucose orally. He regained consciousness after 30 s and started feeling better. He denied having similar episodes in the past or a prior diagnosis of epilepsy. Five minutes later, his serum glucose level was 5.8 mmol/L.

Thereafter, spinal anesthesia was performed continuously and successfully by slow subarachnoid injection of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine (1.5 mL) at the L4-L5 interspace within 2 min. The blocking region was from S1 to S5. A sitting position was maintained for 10 min. Subsequently, the operation was started in the left decubitus position at 7: 25 p.m. Complicated high perianal abscess incision and drainage of primary lesion removal and thread-drawing therapy lasted for about 1 h, and the patient was then returned to the ward at 8: 30 p.m. Throughout the procedure, the patient received 500 mL of Lactated Ringer’s intravenous infusion; the postoperative analgesia protocol was patient-controlled intravenous analgesia (125 μg sufentanil diluted into 100 mL).

Loss of regional blocking effects occurred approximately 6 h after the procedure. Two episodes of transient loss of consciousness, similar to the one described above, occurred at 6.5 h and 8.5 h after procedure, when the patient got out of his bed and walked about 10 m to the toilet. Each episode lasted approximately 30 s, and the patient regained consciousness without assistance. During the last episode, his blood glucose level was 6.9 mmol/L. Postoperative follow-up was conducted at 13 h after surgery. The patient was conscious at this time, and his VAS score was 4 without any symptoms of discomfort; however, he said the VAS score in the toilet was 8. After 3 days in the general ward, he was discharged without any complications.

Discussion

In this case report, we described a 44-year-old man with 3 episodes of syncope due to a vasovagal response during administration of spinal anesthesia and after a procedure for drainage of an anal abscess. Pain caused by perianal abscess during the puncture of spinal anesthesia in the sitting position and postoperative pain after the disappearance of spinal anesthesia could trigger vasovagal syncope.

Vasovagal syncope is believed to be sudden and transient loss of consciousness, hypotension, and bradycardia caused by disorders of autonomic regulation [12,13], which is also known as the Bezold-Jarisch reflex [14] and neurocardiogenic syncope [15]. The causes of vasovagal syncope are diverse and include factors such as bleeding, postural changes, compression of the inferior vena cava, and regional anesthesia [11]. The ultimate result of these factors is increased vagal nerve activity and decreased cardiac output. Vasovagal syncope caused by reflex cardiovascular depression results in a loss of consciousness with bradycardia and profound vasodilation [13]. This commonly occurs while standing for more than 30 s or sitting and is triggered by exposure to emotional stress, pain, or medical settings [16]. It is typically preceded by prodromal symptoms of autonomic nervous system activation, such as sweating, fever, pallor, and nausea [8]. The diagnosis is primarily based on a detailed medical history, physical examination, and observations from eyewitnesses [8].

In the present case, the possible causes of syncope included orthostatic hypotension, hypoglycemic episode, or vasovagal response. According to the patient’s symptoms, signs, medical history, examinations, and head CT scan findings, vasovagal response seemed to be the most probable cause. We ruled out orthostatic hypotension for the following reasons: The first syncope occurred when the patient was in a sitting position, without postural changes. The second and third episodes occurred after he got out of bed and walked about 10 m, but not immediately after standing up. There was no history of autonomic nervous system disease, Parkinson disease, or heart disease, and no obvious blood loss. Furthermore, he was revived within a few seconds of each episode. Orthostatic hypotension is defined as syncope that often occurs after standing up and is accompanied by an aura of short duration. A sudden decrease in blood pressure causes this type of syncope and it often presents in combination with autonomic nervous system disease, Parkinson disease, or occult bleeding [8]. At the first syncope in the operating room, we considered hypoglycemia as a possible cause because the symptoms of the patient’s first syncope closely resembled a hypoglycemic episode. However, in retrospect, we ruled out the possibility for the following reasons: A total of 1000 mL of 5% glucose was administered intravenously 10 h before surgery and 1 h after the procedure. Five minutes after the first and last episodes, the serum glucose levels were 5.8 mmol/L and 6.9 mmol/L, respectively. Most importantly, the patient was free of diabetes.

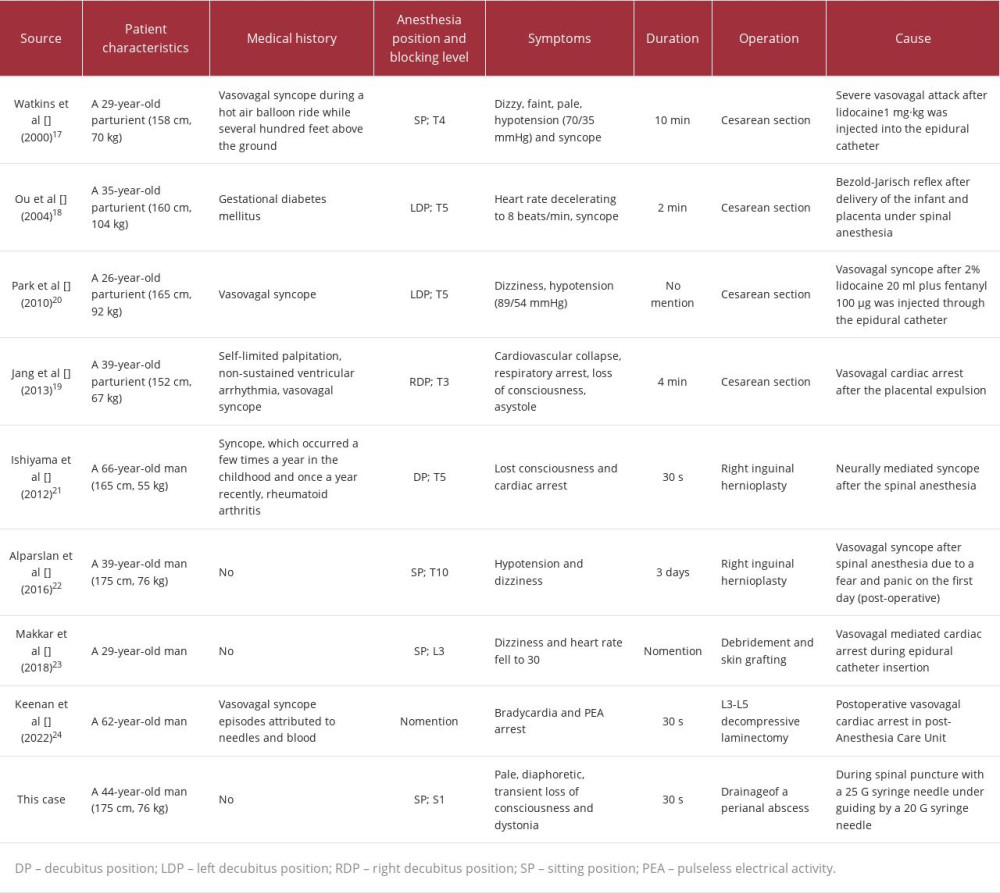

Finally, vasovagal syncope was considered the most probable reason. Only 8 other cases of vasovagal syncope under spinal anesthesia have been reported in the literature. Watkins et al [17] reported a case of vasovagal attack in a patient following epidural injection of lidocaine 1 mg·kg–1 in a sitting position. Ou et al [18] and Yang et al [19] described vasovagal syncope after delivery of an infant and placenta under spinal anesthesia. Park et al [20] reported a case of vasovagal syncope after injecting 20 mL of 2% lidocaine plus 100 µg fentanyl through an epidural catheter. Ishiyama et al [21] presented a case of neurally mediated syncope following administration of spinal anesthesia. Alparslan et al [22] discussed a case of vasovagal syncope observed after administration of spinal anesthesia in the sitting position. Makkar et al [23] reported a case of vasovagal-mediated cardiac arrest in the sitting position during epidural catheter insertion. Keenan4et al [24] reported a case of postoperative vasovagal cardiac arrest in the post-anesthesia care unit. Six of the 8 patients described above experienced syncope related to intrathecal anesthesia, and 3 experienced syncope in the sitting position. In the mentioned cases [17,20], the causes of vasovagal syncope in postpartum women included supine hypotensive syndrome in pregnant women in the supine position, estrogen and progesterone in the blood during labor causing vasodilation, impairment of sympathetic nervous system function below the level of anesthesia, and maternal fear and anxiety. In the cases described by Yang et al [19], acute bleeding during placental delivery and uterine inversion and traction in postpartum women appeared to be key factors triggering the vasovagal neurogenic response. In a study on the impact of body position on hemodynamics during epidural anesthesia [25], researchers compared the effects of sitting and lateral positions on the cerebral stroke index and cardiac index in pregnant women. The results indicated that inserting the epidural catheter in a sitting position was more beneficial for patient outcomes. Makkar et al [23] suggested that young and healthy patients with higher vagal tone are more prone to vasovagal episodes. Even without any local anesthetic administration, simply placing an epidural catheter can lead to severe bradycardia and cardiac arrest. Compared with the mentioned cases, our case highlights 2 points. First, patients can experience vasovagal syncope during the puncture of spinal anesthesia due to anxiety and perianal pain worsening in the sitting position. Second, in our case, the patient also experienced vasovagal syncope again after the disappearance of spinal anesthesia due to the pain that occurred while he went to the toilet. More comparisons in detail between this case and the aforementioned 8 cases are shown in Table 1.

In the present case, syncope was encountered 3 times during perioperative incision and drainage of a simple perianal abscess. The first episode of syncope occurred in the sitting position during the procedure of spinal anesthesia puncture. Pain with the perianal abscess worsened in the sitting position and could have caused the strong vagal reflex leading to bradycardia, hypotension, low cerebral perfusion, and his first episode of syncope. The second and third episodes of syncope occurred after the effects of spinal anesthesia had worn off and he was in the toilet. His VAS score was 4 in the resting condition, although he received patient controlled intravenous analgesia; however, the VAS score in the toilet was 8. Therefore, pain could have been the main reason for the other 2 episodes of syncope in our patient. Patients with blood volume deficits are more vulnerable to vasovagal syncope [26]. In retrospect, our patient fasted for 24 h prior to the surgery, which could have contributed to the vasovagal episodes. In a previous report, reduction of venous return resulting from compression of the inferior vena cava by the gravid uterus was thought to be responsible for vasovagal episode [17]. Similarly, in the present patient, inferior vena cava compression in the sitting position might have caused a reduction in the venous return. In our case, several factors support a vasovagal response as the cause of the sudden fainting. The patient was in a sitting position, which led to the stimulation and excitation of the abundant vagal nerve fibers in the perianal region. Additionally, the patient was exposed to emotional stress and the medical environment, which collectively triggered vasovagal syncope. He had prodromal features, including dizziness, visual blurring, paleness, and diaphoresis. However, there was no history of cardiac or intracranial diseases, and his ECG and cranial CT scan results were normal.

The crucial question is how this patient’s case could have been managed better. First, a careful history taking with focus on prior episodes of fainting or syncope, and diligent preoperative estimation using techniques such as tilt-table testing can help avoid syncope during medical procedures. The tilt table can help clinicians understand the reasons for recurrent transient loss of consciousness in patients with syncope and distinguish neurally mediated syncope from psychogenic pseudosyncope [27]. Second, the sitting position should be avoided in patients with a perianal abscess because the pain increases significantly when sitting. Third, maintenance of adequate cardiac preload before neuraxial anesthesia can help prevent a sudden decrease in venous return. Fourth, intravenous administration of ephedrine can prevent severe reflex bradycardia by stimulating the alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor systems.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we reported a case of 3 episodes of vasovagal syncope in a patient due to a vasovagal response during administration of spinal anesthesia and after procedure for drainage of perianal abscess. Vasovagal syncope can be mainly caused by pain; therefore, the procedure of avoiding puncture of spinal anesthesia in the sitting position and effective postoperative pain management should be managed well for these patients.

References:

1.. Sigmon DF, Emmanuel B, Tuma F, Perianal abscess.: StatPearls., 2023, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing Copyright© 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

2.. Sahnan K, Adegbola SO, Tozer PJ, Perianal abscess: Br Med J, 2017; 356; j475

3.. Rho M, Guida AM, Materazzo M, Ligasure hemorrhoidectomy: Updates on complications after an 18-year experience: Rev Recent Clin Trials, 2021; 16(1); 101-8

4.. Wright WF, Infectious diseases perspective of anorectal abscess and fistula-in-ano disease: Am J Med Sci, 2016; 351(4); 427-34

5.. Choi YS, Kim DS, Lee DH, Clinical characteristics and incidence of perianal diseases in patients with ulcerative colitis: Ann Coloproctol, 2018; 34(3); 138-43

6.. Yuan H, Silberstein SD, Vagus nerve and vagus nerve stimulation, a comprehensive review: Part I: Headache, 2016; 56(1); 71-78

7.. Frøkjaer JB, Bergmann S, Brock C, Modulation of vagal tone enhances gastroduodenal motility and reduces somatic pain sensitivity: Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2016; 28(4); 592-98

8.. Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society.: Circulation., 2017; 136(5); e25-e59 [Erratum in: Circulation. 2017;136(16): e269–e70]

9.. Hainsworth R, Pathophysiology of syncope.: Clin Auton Res, 2004; 14(Suppl. 1); 18-24

10.. Schaal SF, Nelson SD, Boudoulas H, Lewis RP, Syncope.: Curr Probl Cardiol, 1992; 17(4); 205-64

11.. Kinsella SM, Tuckey JP, Perioperative bradycardia and asystole: Relationship to vasovagal syncope and the Bezold-Jarisch reflex: Br J Anaesth, 2001; 86(6); 859-68

12.. McConachie I, Vasovagal asystole during spinal anaesthesia: Anaesthesia, 1991; 46(4); 281-82

13.. Arthur W, Kaye GC, The pathophysiology of common causes of syncope: Postgrad Med J, 2000; 76(902); 750-53

14.. Mark AL, The Bezold-Jarisch reflex revisited: Clinical implications of inhibitory reflexes originating in the heart: J Am Coll Cardiol, 1983; 1(1); 90-102

15.. Pachon MJ, Neurocardiogenic syncope: Pacemaker or cardioneuroablation?: Heart Rhythm, 2020; 17(5 Pt A); 829-30

16.. Sheldon RS, Grubb BP, Olshansky B, 2015 heart rhythm society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope: Heart Rhythm, 2015; 12(6); e41-63

17.. Watkins EJ, Dresner M, Calow CE, Severe vasovagal attack during regional anaesthesia for caesarean section: Br J Anaesth, 2000; 84(1); 118-20

18.. Ou CH, Tsou MY, Ting CK, Occurrence of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex during Cesarean section under spinal anesthesia – a case report: Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan, 2004; 42(3); 175-78

19.. Jang Y-E, Do S-H, Song I-A, Vasovagal cardiac arrest during spinal anesthesia for Cesarean section – A case report: Korean J Anesthesiol, 2013; 64(1); 77-81

20.. Park SY, Kim SS, An anesthetic experience with cesarean section in a patient with vasovagal syncope – a case report: Korean J Anesthesiol, 2010; 59(2); 130-34

21.. Ishiyama T, Shibuya K, Terada Y, Cardiac arrest after spinal anesthesia in a patient with neurally mediated syncope: J Anesth, 2012; 26(1); 103-6

22.. Alparslan MM, Ekim MŞ, Yılmaz A, Vasovagal syncope developed after spinal anesthesia: A case report: Basic Clin Sci, 2016; 4(3); 132-35

23.. Makkar JK, Jain D, Jain K, Pareek A, Vasovagal mediated cardiac arrest during epidural catheter insertion in a patient with previous uneventful surgeries under regional anesthesia: J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol, 2018; 34(2); 268-69

24.. Keenan C, Wang AY, Balonov K, Kryzanski J, Postoperative vasovagal cardiac arrest after spinal anesthesia for lumbar spine surgery: Surg Neurol Int, 2022; 13; 42

25.. Chadwick IS, Eddleston JM, Chandelier CK, Pollard BJ, Haemodynamic effects of the position chosen for the insertion of an epidural catheter: Int J Obstet Anesth, 1993; 2(4); 197-201

26.. El-Sayed H, Hainsworth R, Relationship between plasma volume, carotid baroreceptor sensitivity and orthostatic tolerance: Clin Sci, 1995; 88(4); 463-70

27.. Grubb BP, Temesy-Armos P, Hahn H, Elliott L, Utility of upright tilt-table testing in the evaluation and management of syncope of unknown origin: Am J Med, 1991; 90(1); 6-10

In Press

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943467

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250