24 August 2023: Articles

Thyroid Storm-Induced Refractory Multiorgan Failure Managed by Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support: A Case-Series

Unusual clinical course, Management of emergency care

Mugahid Eltahir1ABDEF, Hamza Chaudhry2ABDE, Ezzeddin Abdulsalam Ibrahim1ABD, Marwa Mokhtar3BD, Hani Jaouni12ABCE, Ibrahim Fawzy Hassan12DE, Ayman El-MenyarDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.940672

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e940672

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Severe hyperthyroidism, including thyroid storm, can be precipitated by acute events, such as surgery, trauma, infection, medications, parturition, and noncompliance or stoppage of antithyroid drugs. Thyroid storm is one of the serious endocrinal emergencies that prompts early diagnosis and treatment. Early occurrence of multiorgan failure is an ominous sign that requires aggressive treatment, including the initiation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support as a bridge to stability and definitive surgical treatment. Most adverse events occur after failure of medical therapy.

CASE REPORT: We described 4 cases of fulminating thyroid storm that were complicated with multiple organ failure and cardiac arrest. The patients, 3 female and 1 male, were between 39 and 46 years old. All patients underwent ECMO support, with planned thyroidectomy. Three survived to discharge and 1 died after prolonged cardiac arrest and sepsis. All patients underwent peripheral, percutaneous, intensivist-led cannulation for VA-ECMO with no complications.

CONCLUSIONS: Early recognition of thyroid storm, identification of the cause, and proper treatment and support in the intensive care unit is essential. Patients with thyroid storm and cardiovascular collapse, who failed to improve with conventional supportive measures, had the worst prognosis, and ECMO support should be considered as a bridge until the effective therapy takes effect. Our case series showed that, in patients with life-threatening thyroid storm, VA-ECMO can be used as bridge to stabilization, definitive surgical intervention, and postoperative endocrine management. Interprofessional team management is essential, and early implantation of VA-ECMO is likely beneficial in patients with thyroid storm after failure of conventional management.

Keywords: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, Heart, Hyperthyroxinemia, Multiple Organ Failure, Humans, Female, Male, Pregnancy, Adult, Middle Aged, Thyroid Crisis, Delivery, Obstetric

Background

Thyroid storm is a life-threatening form of severe hyperthyroidism characterized by acute generalized manifestations [1]. National surveys from the United States and Japan reported that the incidence of thyroid storm ranges from 0.20 to 0.76 cases per 100 000 persons per year, with higher incidence in hospitalized patients (4.8 to 5.6 per 100 000) [2–4]. Severe hyperthyroidism can be precipitated by acute events, including surgery, trauma, infection, an acute iodine load (ie, amiodarone administration), parturition, and noncompliance or stoppage of antithyroid drugs [2,3,5–7]. The evolution from simple thyrotoxicosis to the crisis of thyroid storm usually necessitates an overlaid insult [8]. The diagnosis of thyroid storm depends on the presence of serious, and sometimes devastating, presentations including fever, cardiovascular collapse, altered mentation, elevated free T4 and/or T3, and suppressed thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) [5,7,8]. The precise reason why some patients develop thyroid storm rather than uncomplicated thyrotoxicosis is not fully understood; however, some theories suggest a rapid increase in serum thyroid hormone levels, increased responsiveness to catecholamines, or enhanced cellular responses to thyroid hormone [6]. Burch and Wartofsky introduced a scoring system that uses precise clinical criteria to identify thyroid storm. However, this scoring system is likely sensitive but not specific [9]. The diagnostic criteria for thyroid storm include thermoregulatory dysfunction (score 5–30), central nervous system effects (score 10–30), gastrointestinal-hepatic dysfunction (score between 10–20), cardiovascular dysfunction (score 5–25 for tachycardia, 10 for atrial fibrillation, and 5–15 for heart failure), and presence of precipitant history (0 vs 10). A score of 45 or more is highly suggestive of thyroid storm; a score of 25 to 44 supports the diagnosis [10].

The principles of therapeutic options typically consist of a couple of medications, each of which has a different mechanism of action. The treatment options are based upon clinical experience and case studies, since there are no prospective studies. The treatment is extrapolated from those used for uncomplicated hyperthyroidism, with additional drugs such as glucocorticoids, iodine solution, and high doses of antithyroid drugs. In addition to specific therapy to inhibit the release and reduce the synthesis of thyroid hormones, supportive therapy in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and treating the precipitating factors are essential; however, the mortality rate of thyroid storm is high (10%–30%) [9].

In thyroid storm with hemodynamic instability and cardiogenic shock, antithyroid medications can be contraindicated due to multiorgan failure, especially in case of liver involvement. Also, the administration of beta blockers to patients with thyroid storm can lead to hemodynamic instability and even cardiac arrest [11]. In case of a refractory circulatory collapse, veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) support can be used to achieve hemodynamic stability until normalization of the thyroid hormone, and improvement of the signs and symptoms are achieved. In fulminant multiorgan failure (MOF), therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) can be used as a bridging therapy for reducing the circulating excessive hormones and stabilization of patients in preparation for urgent thyroidectomy [12]. The challenges of commencing plasma exchanges with ongoing ECMO support, dialysis, and timing of thyroidectomy are still to be explored [13–15]. TPE has shown an additive effect to the continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) in removing the excess thyroid hormones4[14,16]. Furthermore, the use of 3 extra-corporeal systems together (TPE, CRRT, and VA-ECMO) was reported in a few case reports for thyroid storm management [13,14].

Here, we describe 4 cases of life-threatening thyroid storm complicated with circulatory collapse and multiorgan failure and requiring VA-ECMO support, renal replacement therapy, and TPE, with planned urgent thyroidectomy.

Case Reports

CASE 1:

A 39-year-old woman presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with symptoms suggestive of thyroid storm. The patient scored 55 points using the Burch Wartofsky Point Scale for thyroid storm diagnosis. She had atrial fibrillation (Figure 1), poor left ventricular function, pleural effusion, and ascites. She was not known to have comorbidities. The patient was initially treated with intravenous (i.v.) metoprolol and synchronized cardioversion. Despite these interventions, the patient developed bradycardia followed by cardiac arrest. The patient’s cardiovascular instability and the need for maximum vasopressors prompted the decision to initiate ECMO support. After her admission to the ICU, the patient’s blood tests confirmed the diagnosis of thyroid storm, with MOF and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Medical treatment with antithyroid medication was not possible because of MOF, and therefore plasmapheresis was started as a bridging to thyroidectomy. Plasmapheresis helped to optimize her condition so that she could undergo thyroidectomy (Figure 2). Following thyroidectomy, the patient’s general condition and left ventricular function improved. The patient’s TSH increased to 0.74 mIU/L and free T4 decreased to 36.1 pmol/L. She was transferred to the medical ward and then was discharged home in a stable condition.

CASE 2:

A 42-year-old woman presented to the ED with symptoms consistent with thyroid storm. She claimed only a history of a “thyroid problem” but was not taking any treatment for it. On examination, she was ill with jaundice and cold, clammy skin. Her ECG showed atrial flutter. Briefly after beta blocker administration, she went into cardiac arrest, with pulseless electrical activity. She was resuscitated, intubated, and started on vasopressors. Point-of-care ultrasound demonstrated significantly dilated heart chambers, with markedly reduced ejection fraction and bilateral pleural effusion. The patient’s laboratory findings were suggestive of thyroid storm, MOF, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Her TSH was less than 0.01 mIU/L, free T4 was 38.9 pmol/L, and her thyroid peroxidase antibodies were also found to be markedly elevated. Using the Burch Wartofsky Point Scale, the patient scored 70 points. The ECMO team was consulted, as she was in cardiogenic shock. Uneventful peripheral percutaneous cannulation and initiation of VA-ECMO allowed for improvement of cardiovascular parameters. On day 2, she was started on CRRT, specifically continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration. A second plasmapheresis session was conducted on day 3, and a third session on day 4 in the ICU. An ultrasound examination of the thyroid gland demonstrated a diffusely heterogenous thyroid with increased vascularity, suggestive of thyroiditis. Furthermore, a thyroid scan with radioactive iodine uptake was suggestive of Graves’ disease. By day 5 in the ICU, interval improvements were noted after the intermittent plasma-pheresis treatments and CRRT.

On day 7, she underwent a total thyroidectomy. The patient underwent decannulation of the VA-ECMO, as her cardiac function significantly improved, with an ejection fraction of 45%. Additionally, her liver enzymes were trending downward. Five days after thyroidectomy, the free T4 returned within the normal range, and she was extubated 2 days later. She was transferred to the medical ward for few weeks and then she was discharged in a stable condition.

CASE 3:

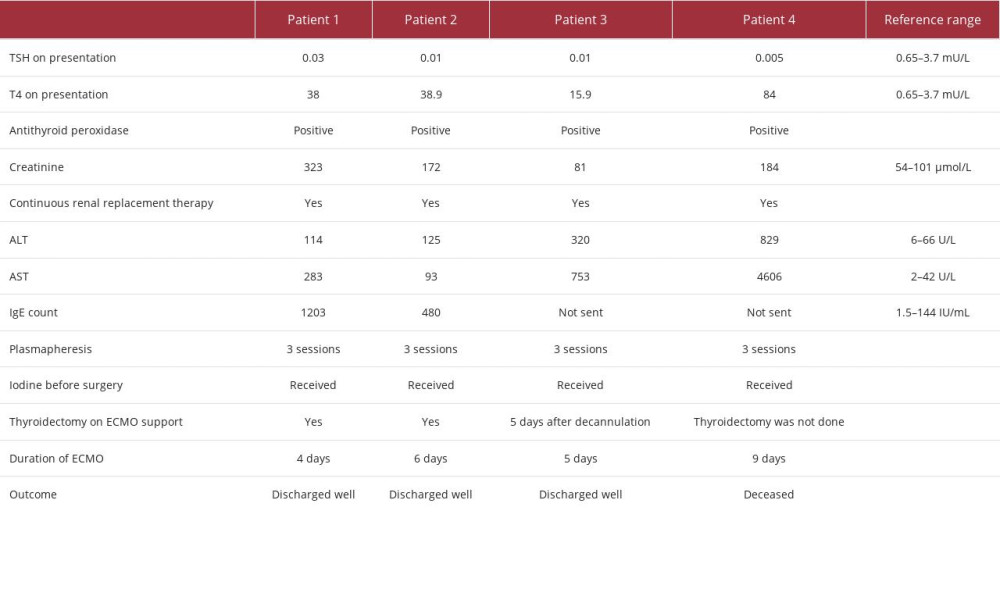

A 46-year-old woman presented to the ED with abdominal distension, nausea, exophthalmos, palpitation, and hand tremors. She denied any prior comorbidities. The patient’s Burch Wartofsky score was 55 points. The diagnosis of thyroid storm was confirmed by elevated T3 levels and suppressed TSH. Initially, she received intravenous fluids, propranolol, hydrocortisone, and propylthiouracil. However, due to the development of cardiogenic shock and multiorgan dysfunction, propylthiouracil was discontinued because of severe liver failure, and the patient required intubation for respiratory support. Further evaluation revealed severe bi-ventricular failure, with an ejection fraction of 15% on echocardiography. To support the compromised heart and lungs, the patient received a combination of adrenaline, noradrenaline, and levosimendan. Despite these interventions, her condition continued to deteriorate. In response to the worsening clinical picture, the decision was made to initiate ECMO for advanced cardiac and respiratory support. Following the initiation of ECMO, a significant improvement and thyroidectomy was performed on day 12 of admission for a large goitre. Following surgery, 2 additional plasmapheresis sessions were conducted to normalize the patient’s free T4 levels, which had declined with each session. The combined interventions, including surgery and plasmapheresis, successfully restored the patient’s free T4 levels to the normal range. Subsequently, the patient was transferred to the medical ward and eventually discharged from the hospital. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the clinical and laboratory findings as well as the outcomes of all the cases.

CASE 4:

A 43-year-old man presented to the ED with dyspnea, palpitations, non-productive cough, watery diarrhea, and fever. He had a past medical history of only Graves’ disease, which was diagnosed 3 months earlier and was treated with propranolol and propylthiouracil. He was scheduled for radioactive iodine ablation therapy; however, had stopped taking carbimazole for the last 2 weeks. The patient scored 65 points on the Burch Wartofsky Point Scale, confirming the thyroid storm status. On examination, he was found to have an irregular pulse and severe global hypokinesis on bedside echocardiogram. He was given adenosine and metoprolol for supraventricular tachycardia; however, he developed cardiac arrest, with pulseless electrical activity. Spontaneous circulation was achieved after 14 cycles, and then he was put on VA-ECMO and CRRT to support the failing heart and kidneys. The thyroid storm led to MOF, and therefore he was started on plasmapheresis as a bridging therapy to eventual thyroidectomy and to help remove circulating thyroid hormones and immune mediators. The patient was clinically and hemodynamically improving; therefore, decannulation of ECMO was performed on day 8. He was scheduled for thyroidectomy on the first day after ECMO decannulation. However, the neurology team observed poor neurological responses. The electro-encephalogram demonstrated severe hypoxic encephalopathy; therefore, thyroidectomy was declined. On day 12, the patient developed sepsis due to gram-negative bacteremia and went into refractory septic shock and asystole, and eventually died.

Discussion

USE OF BETA BLOCKERS IN THYROID STORM:

In all of our patients, the decision was made by the ED team to control the heart rate with beta blockers. However, the patients started to deteriorate soon after the administration of beta blockers and had to be placed on ECMO, due to life-threatening cardiovascular instability. The mechanism of how hyperthyroidism induces a hyperadrenergic state and its effects on the cardiovascular system are complex [18]. A systematic review found 9 published reports of beta blocker-induced cardiovascular collapse, and case reports addressed the occurrence of cardiovascular collapse after the use of beta blockers [11,19].

All of our patients had clinical evidence of heart failure on presentation and low ejection fraction of 20% to 25%. We suggest extreme precaution and/or avoidance of the use of long-acting beta blocking agents in those patients. Ultra-short-acting beta blockers that are easy to titrate may be a suitable alternative in this subset of patients.

USE OF ECMO IN THYROID STORM:

ECMO is used in critical care when conventional therapies fail to provide enough oxygenation and/or cardiac output. VA-ECMO is a form of extracorporeal life support and temporary mechanical circulatory support, in which blood is withdrawn from a large vein, passes through an oxygenator, and is returned to a major artery. It provides a bridge to recovery, allowing time for the patient’s heart and lungs to heal [20]. In our institution, VA-ECMO is provided in the medical ICU and performed by the intensivist via a percutaneous Seldinger approach, using the femoral vein and artery.

ECMO is not a standard treatment for thyroid storm; however, in very severe and refractory cases of thyroid storm, in which the patient is critically ill, ECMO can be considered as a last-resort therapy [21]. ECMO can provide temporary support for the patient’s heart and lung function while the underlying thyroid condition and MOF is treated, which can help to stabilize the patient’s condition and improve their chance of survival. However, ECMO is a complex and invasive procedure that requires a high level of expertise and should only be performed in specialized centers. Of note, the use of VA-ECMO support can be deferred if a rapid stabilization of the hemodynamics could be achieved prior to thyroidectomy [16]. Our patients experienced refractory cardiovascular collapse and after multiple resuscitation attempts, and it was decided to initiate ECMO support. The effect of high thyroid hormones can alter the sensitivity or responsiveness of various tissues to catecholamines and can yield the medication less effective [8,18,19]. Therefore, in these cases of refractory cardiogenic shock, an early initiation of patient on ECMO might help stabilize the patient until the definitive treatment is delivered. Follow-up echocardiogram demonstrated improvement in the ejection fraction in all patients, who were subsequently weaned and decannulated successfully from ECMO.

USE OF PLASMAPHERESIS:

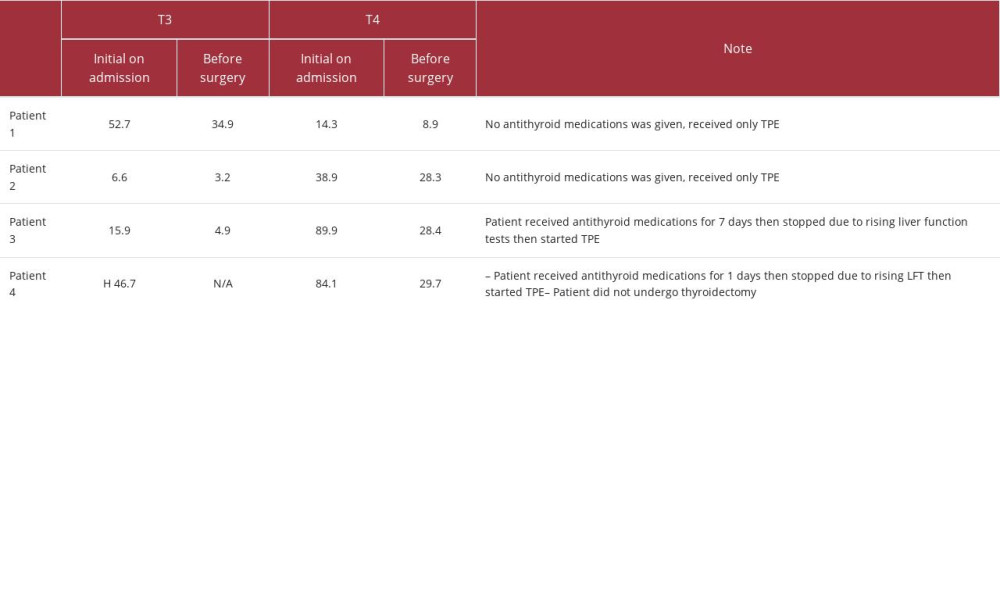

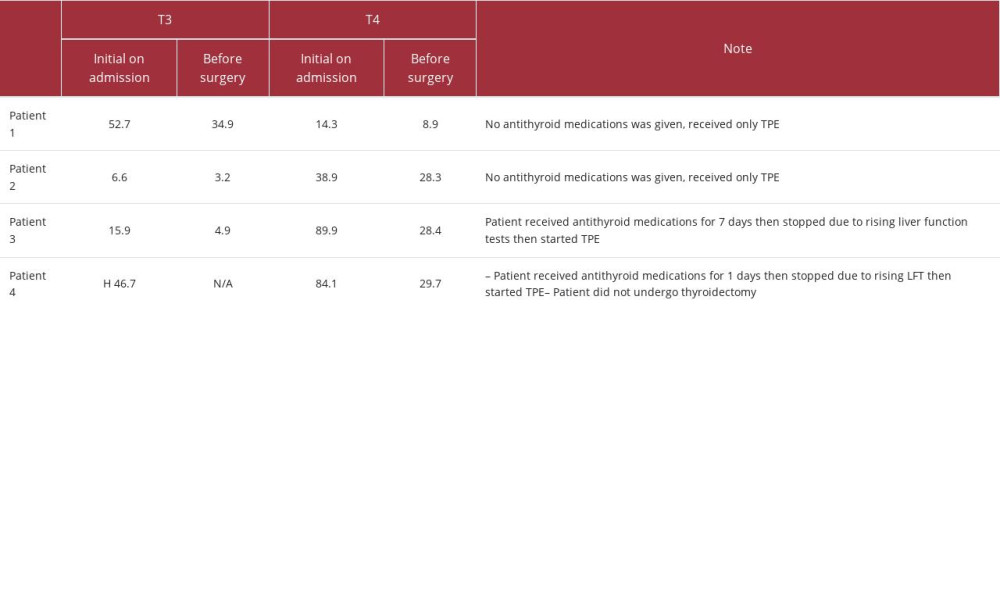

Plasmapheresis, or TPE (extra-corporeal blood purification technique), acts via extracorporeal separation and removal of plasma through centrifugation. This will remove plasma proteins with bound T3/T4 resulting in a rapid decrease of thyroid hormones [22]. In the case of a thyroid storm, plasma-pheresis is not a standard of care, but it can be considered in some cases as an adjunctive therapy to help lower the levels of thyroid hormones as early as possible [23,24]. Binimelis et al described a 30-fold decrease in total thyroxine levels with plasma exchange as compared with conventional treatment, and this effect was proportional to the serum level of thyroxine [25]. Rapid clinical improvement was apparent in our patients after the first 2 plasma exchanges, and there was also improvement in the serum FT3 and FT4 levels (Table 3).

THYROIDECTOMY IN THYROID STORM UNDER ECMO SUPPORT:

In thyroid storm, surgical intervention is not a first-line treatment; however, it can be considered in selected cases, as the mainstay of treatment remains medical management. Our patients went rapidly into cardiorespiratory failure despite maximum medical therapy; therefore, the professional medical team decided to go for urgent thyroidectomy under ECMO support. In thyroid storm, thyroidectomy is associated with an overall mortality rate of 10%, which is why surgery is not the first choice [1,22,26]. However, the criteria to decide when patients with thyroid storm should undergo thyroidectomy are lacking. Therefore, thyroidectomy should only be considered as a treatment option for thyroid storm on case-by-case basis, provided that the benefits outweigh the risks and that the patient is not responding to other treatments.

Conclusions

Early recognition of thyroid storm, identification of the cause, and appropriate treatment and support in the ICU are essential to improve the outcome. Patients with cardiovascular collapse, who fail to improve with conventional supportive measures, have the worst outcomes, and ECMO support could be utilized as a bridge until the effective therapy takes effect. Our limited experience showed that in patients with life-threatening thyroid storm, VA-ECMO can be used as bridge to stabilization, definitive surgical intervention, and postoperative endocrine management. Interprofessional team management is essential, and early implantation of VA-ECMO is likely to be beneficial.

References:

1.. Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J, Wartofsky L, Thyroid emergencies: Med Clin North Am, 2012; 96(2); 385-403

2.. Akamizu T, Satoh T, Isozaki O, Diagnostic criteria, clinical features, and incidence of thyroid storm based on nationwide surveys: Thyroid, 2012; 22(7); 661-79 [Erratum in: Thyroid. 2012;22(9):979]

3.. Akamizu T, Thyroid storm: A Japanese perspective.: Thyroid, 2018; 28(1); 32-40

4.. Galindo RJ, Hurtado CR, Pasquel FJ, National trends in incidence, mortality, and clinical outcomes of patients hospitalized for thyrotoxicosis with and without thyroid storm in the United States, 2004–2013: Thyroid, 2019; 29(1); 36-43

5.. Swee du S, Chng CL, Lim A, Clinical characteristics and outcome of thyroid storm: A case series and review of neuropsychiatric derangements in thyrotoxicosis: Endocr Pract, 2015; 21(2); 182-89

6.. Ono Y, Ono S, Yasunaga H, Factors associated with mortality of thyroid storm: Analysis using a national inpatient database in Japan: Medicine (Baltimore), 2016; 95(7); e2848

7.. de Mul N, Damstra J, Nieveen van Dijkum EJM, Risk of perioperative thyroid storm in hyperthyroid patients: A systematic review: Br J Anaesth, 2021; 127(6); 879-89

8.. Chiha M, Samarasinghe S, Kabaker AS, Thyroid storm: an updated review: J Intensive Care Med, 2015; 30(3); 131-40

9.. Idrose AM, Acute and emergency care for thyrotoxicosis and thyroid storm: Acute Med Surg, 2015; 2(3); 147-57

10.. Burch HB, Wartofsky L, Life-threatening thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid storm: Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am, 1993; 22(2); 263-77

11.. Dalan R, Leow MK, Cardiovascular collapse associated with beta blockade in thyroid storm: Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes, 2007; 115(6); 392-96 [Erratum in: Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2007;115(10):696; Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2008;116(1):72]

12.. Koball S, Hickstein H, Gloger M, Treatment of thyrotoxic crisis with plasmapheresis and single pass albumin dialysis: A case report.: Artif Organs, 2010; 34(2); E55-58

13.. Amos S, Pollack R, Sarig I, VA-ECMO for thyroid storm: Case reports and review of the literature: Isr Med Assoc J, 2023; 25(5); 349-50

14.. Lim SL, Wang K, Lui PL, Crash landing of thyroid storm: A case report and review of the role of extra-corporeal systems: Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2021; 12; 725559

15.. Haley PA, Zabaneh I, Bandak DN, Iskapalli MD, The resolution of thyroid storm using plasma exchange and continuous renal replacement therapy: J Adv Biol Biotechnol, 2019; 20(1); 1-4

16.. Kennell TI, Daley L, Minish J, Krick S, Thyroid storm leading to cardiogenic shock: To ECMO or not to ECMO: Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2023; 207; A6691

17.. Carroll R, Matfin G, Endocrine and metabolic emergencies: Thyroid storm: Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab, 2010; 1(3); 139-45

18.. Shahid MA, Ashraf MA, Sharma S, Physiology, thyroid hormone.: StatPearls [Internet]. May 8, 2022, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing 2023

19.. Alahmad M, Al-Sulaiti M, Abdelrahman H, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support and total thyroidectomy in patients with refractory thyroid storm: Case series and literature review.: J Surg Case Rep., 2022; 2022(5); rjac131

20.. : ELSO guidelines for cardiopulmonary extracorporeal life support. Version 1.4, 2021, Ann Arbor, MI, ELSO

21.. Hsu LM, Ko WJ, Wang CH, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation rescues thyrotoxicosis-related circulatory collapse.: Thyroid, 2011; 21(4); 439-41

22.. De Almeida R, McCalmon S, Cabandugama PK, Clinical review and update on the management of thyroid storm: Mo Med, 2022; 119(4); 366-71

23.. Dyer M, Neal MD, Rollins-Raval MA, Raval JS, Simultaneous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and therapeutic plasma exchange procedures are tolerable in both pediatric and adult patients: Transfusion, 2014; 54(4); 1158-65

24.. Vyas AA, Vyas P, Fillipon NL, Vijayakrishnan R, Trivedi N, Successful treatment of thyroid storm with plasmapheresis in a patient with methimazole-induced agranulocytosis: Endocr Pract, 2010; 16(4); 673-76

25.. Binimelis J, Bassas L, Marruecos L, Massive thyroxine intoxication: Evaluation of plasma extraction: Intensive Care Med, 1987; 13(1); 33-38

26.. Baeza A, Aguayo J, Barria M, Pineda G, Rapid preoperative preparation in hyperthyroidism: Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 1991; 35(5); 439-42

Figures

Tables

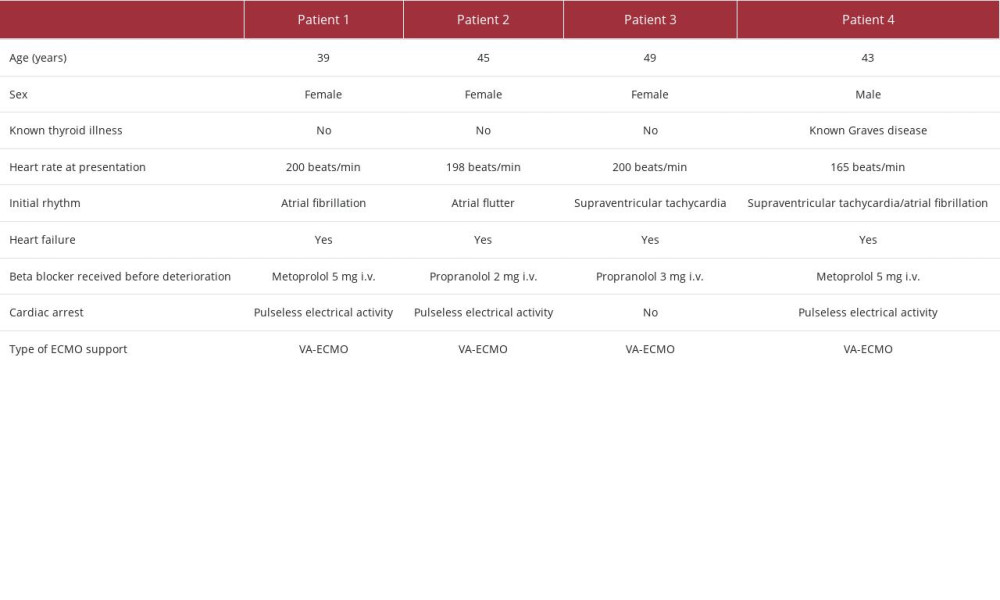

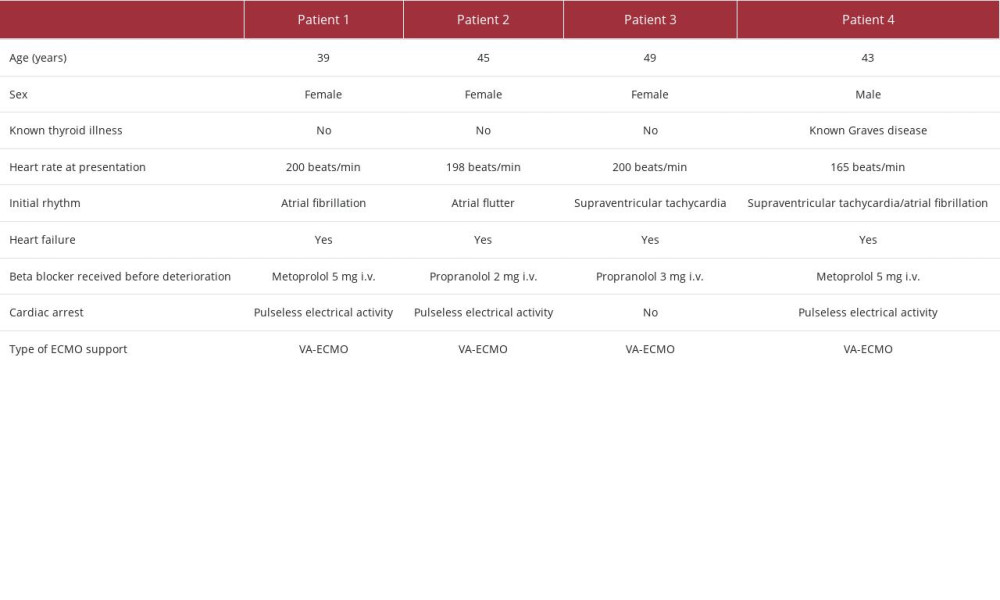

Table 1.. Patient demographics and initial presentation of the 4 cases.

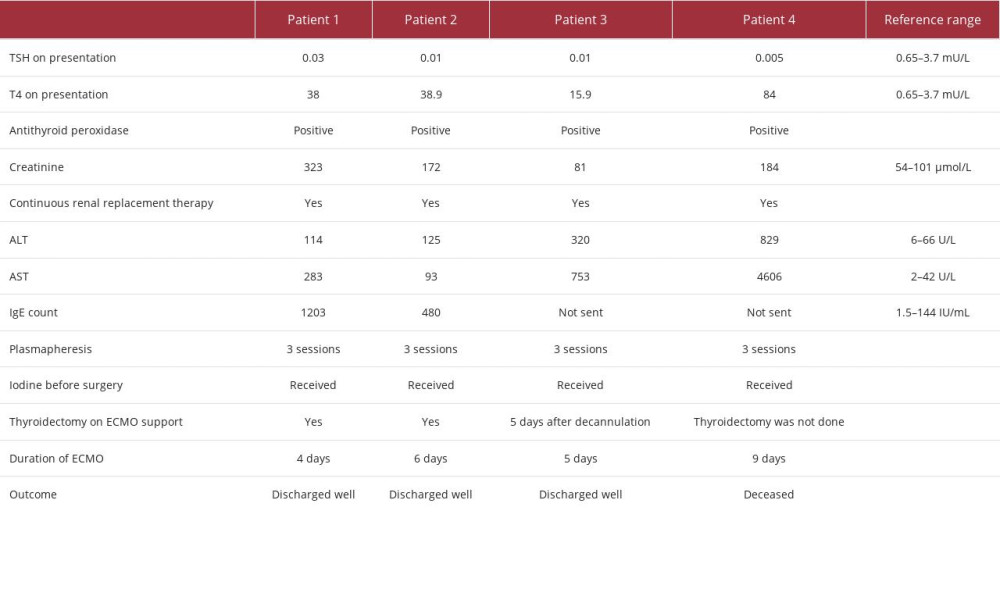

Table 1.. Patient demographics and initial presentation of the 4 cases. Table 2.. Laboratory tests and outcomes of the 4 cases.

Table 2.. Laboratory tests and outcomes of the 4 cases. Table 3.. T3 and T4 levels before and after therapeutic plasmapheresis (TPE) session and just before surgery.

Table 3.. T3 and T4 levels before and after therapeutic plasmapheresis (TPE) session and just before surgery. Table 1.. Patient demographics and initial presentation of the 4 cases.

Table 1.. Patient demographics and initial presentation of the 4 cases. Table 2.. Laboratory tests and outcomes of the 4 cases.

Table 2.. Laboratory tests and outcomes of the 4 cases. Table 3.. T3 and T4 levels before and after therapeutic plasmapheresis (TPE) session and just before surgery.

Table 3.. T3 and T4 levels before and after therapeutic plasmapheresis (TPE) session and just before surgery. In Press

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942853

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942660

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943174

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943136

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250