02 October 2023: Articles

A Rare Case of Subcutaneous Amyloidoma Associated with Localized Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma: Diagnostic Challenges and Treatment Considerations

Rare disease, Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Lisa Francesca VivianDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.940789

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e940789

Abstract

BACKGROUND: AL amyloidomas are solitary, localized, tumor-like deposits of immunoglobulin light-chain-derived amyloid fibrils in the absence of systemic amyloidosis. A rare entity, they have been described in various anatomical sites, typically in spatial association with a sparse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, ultimately corresponding to a clonal, malignant, lymphomatous disorder accounting for the amyloidogenic activity. Most frequently, the amyloidoma-associated hematological disorder corresponds to either a solitary plasmacytoma or an extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of MALT. Much rarer is the association with lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, which by itself is usually a bone marrow-bound disorder with systemic burden. The almost anecdotic combination of an amyloidoma and a localized lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma deserves attention, as it entails a thorough diagnostic workup to exclude systemic involvement and a proportionate therapeutic approach to avoid overtreatment. A review of the literature provides an insight on pathogenesis and prognosis, and can assist both pathologists and clinicians in establishing optimal patient management strategies.

CASE REPORT: We herein report the incidental finding of a subcutaneous amyloidoma caused by a spatially related, similarly localized lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma diagnosed in a 54-year-old female patient with no other disease localizations and a complete remission following 2 subsequent surgical excisions.

CONCLUSIONS: Whatever the specific combination of an amyloidoma and the related hematological neoplasm, a multidisciplinary collaboration and a comprehensive clinical-pathological staging are warranted to exclude systemic involvement and identify patients with localized diseases who would benefit from local active treatment and close follow-up.

Keywords: Amyloidosis, literature review, case report, Lymphoma, B-Cell, Female, Humans, Middle Aged, Amyloid, Lymphoma, B-Cell, Marginal Zone, Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia, Plasmacytoma, Soft Tissue Neoplasms

Background

The definition of “amyloid” broadly applies to any extracellular proteinaceous deposition with distinct ultrastructural and microscopic properties and a basic structure represented by a cross β-sheet fibril [1]. In medical practice, the term amyloidosis is used to describe the disrupting consequences of a pathologic amyloid aggregation in organs and tissues – the disease caused by amyloid fibril deposition. So far, as many as 42 amyloidogenic proteins have been recognized in humans and characterized with regards to the disease they may cause [1]. In particular, the accumulation of aberrant immunoglobulin (Ig) light chains is responsible for AL amyloidosis, which can manifest both as a systemic and a localized disease and is caused by a plasmacytic or, more rarely, lymphoplasmacytic-differentiated clone capable of secretory activity. When systemic, the plasmacytic-differentiated Ig-secreting clone is usually located in the bone marrow and corresponds to a plasma cell myeloma or another systemic B-cell lymphoma, including lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL) [2]. In the case of amyloidomas, localized tumor-like deposits of AL amyloid are found in the absence of systemic amyloidosis. These are rarer in daily practice and have been generally described in spatial relation to a similarly localized lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate that, when clonal, most frequently takes the form of a plasmacytoma or extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (ENMZL) of MALT [2]. We herein report on a unique case of subcutaneous amyloidoma associated with an adjacent localized, molecularly-characterized LPL encountered during routine diagnostic practice in the Pathology Department of UZ Leuven. Based on our literature review, the combination of an amyloidoma and a localized, extramedullary LPL is almost only anecdotal [3–5], representing a challenging event that brings about special pathological, clinical, and therapeutical considerations.

Case Report

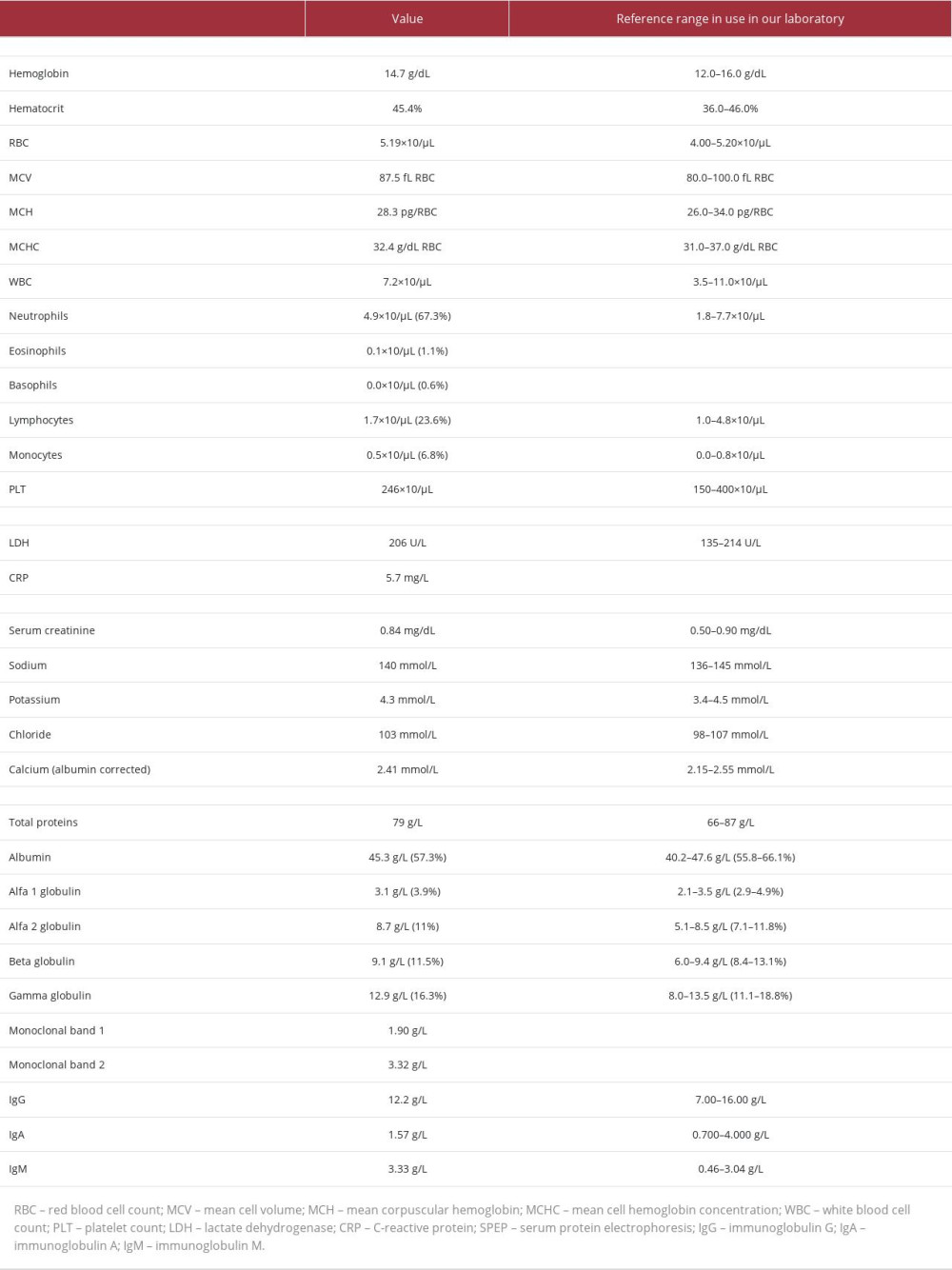

A 54-year-old woman with unremarkable clinical history presented to her treating physician with a subcutaneous swelling of the elbow present for a couple of months. No recent trauma was on record. The lesion was not painful and caused only local discomfort. She had no other concerns, and had no systemic symptoms such as fever or general malaise. Physical evaluation revealed a soft, non-pulsatile, non-fluctuant mass, which was not fixed to the overlying skin or to the underlying deep planes. There were no other clinically relevant findings, particularly no other organomegaly or palpable lymphadenopathies. Laboratory tests revealed normal complete blood counts and LDH values, with the only relevant biochemical finding being a slight increase in serum IgM/κ, just above the significant threshold (Table 1). Subsequently, the clinicians suggested surgically removing the lesion and submitting it for pathological examination.

Macroscopically, the sample was described as a nodular structure measuring 4×1.8 cm, with a rubbery appearance on cut surface. On hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, it was possible to observe an ill-defined nodule of homogenous, amorphous, glassy, pink material permeating the subcutaneous soft tissue (Figure 1A). Occasional patchy cellular aggregates were scattered throughout (Figure 1B), and closer evaluation revealed that they consisted of a mixed population of small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and numerous plasmacytoid lymphocytes, with many nuclear Dutcher bodies (Figure 1C). A focal, perivascular cluster of multinucleated giant cells was also noted (Figure 1D). During immunohistochemical analysis, CD20 confirmed the presence of a conspicuous population of small B lymphocytes (Figure 1E) that were also expressing BCL2 (not shown). Both CD138 and MUM1 highlighted the plasmacytic-differentiated component (Figure 1F), showing variable intensity between proper plasma cells (stronger) and plasmacytoid B cells (weaker). Ig κ light-chain restriction was demonstrated (Figure 1G), alongside diffuse IgM expression with a differential immunoreactivity between the lymphocytic component (membranous) and the plasmacytic population (cytoplasmic); interestingly, the extracellular material was also consistently stained by IgM (Figure 1H). No expression of CD10, BCL6, CD5, CD23, LEF1, CD56, or CYCLIN D1 was detected (not shown). A very limited number of accompanying CD3+ T cells were present. The proliferative index (Ki-67+ cell count) was very low, estimated at around 5%. The amorphous extracellular pink material permeating the soft tissue and thickening the blood vessel walls stained brilliantly with Congo red (Figure 2A, 2C) and showed a typical apple-green birefringence under polarized light (Figure 2B, 2D), thus confirming it corresponded to amyloid deposition. The clonal, neoplastic nature of the cellular proliferation was confirmed by molecular analysis, which showed a monoclonal rearrangement of the IGK gene. Moreover, a c.794T>C (p. (L265P)) mutation in the MYD88 gene was detected in 81% of the cells in the sample. Altogether, the morphological, immunophenotypical, and molecular findings led to a diagnosis of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (ICD-O 9671/3), located in close spatial relationship to a nodular deposition of amyloid – a so-called amyloidoma. Because of the intimate admixture between amyloid and subcutaneous soft tissue, completeness of excision could not be guaranteed.

This diagnosis prompted further systemic evaluation for staging purposes. A thoraco-abdominal spiral CT was performed, which did not show any other suspicious lesions or possible disease localizations. The bone marrow was evaluated both morphologically (aspirate smear, bone core biopsy) and immunophenotypically (flow cytometry), and no evidence was found for the presence of monoclonal B- or T-cell populations or invasion by a lymphoproliferative disease. Consequently, given the single extra-lymphatic site involved and the absence of other nodal or systemic burden, the patient was given a stage of IE and started a wait-and-see approach with periodical check-ups.

At 1-month follow-up, the general practitioner noticed a palpable irregular hardening at the level of the scar, together with a second small bystander nodule. Ultrasound studies revealed a suspicious, irregularly-shaped, hypoechogenic mass with focal vascularization, thus considered worthy of further study and eligible for surgical removal (Figure 3). The sample submitted for histopathological evaluation included 4 fragments, the largest measuring 1.3×1 cm. At microscopic evaluation, the overall picture was identical to that of the patient’s previous biopsy, showing large conglomerates of abundant amorphous, homogenous, glassy, pink extracellular material, embedding patchy and anastomosing aggregates of lymphoplasmacytic cells with several Dutcher bodies (Figure 4A, 4B). Immunohistochemical analysis highlighted numerous PAX5+ B cells (Figure 4C) admixed with an extensive population of CD138+ (Figure 4D), CD56- plasmacytoid cells, both showing Ig κ light-chain-restriction (Figure 4E). A proliferative index of 5-10% was estimated by Ki-67 labeling (not shown). The Congo red stain reconfirmed the amorphous material to be amyloid, showing the typical apple-green birefringence under polarized light (Figure 4F). All things considered, the lesion was regarded as a localization of the known amyloidoma-associated, Ig κ light-chain-restricted LPL, variably interpretable as a very early relapse or a residual disease in the context of an incomplete excision. The multidisciplinary clinical team confirmed the active surveillance program with regular follow-ups, reserving additional treatment options only in case of systemic evolution.

At the last follow-up (23 months), the patient was stable and completely disease-free.

Discussion

We herein report on a unique case in which a localized, molecularly-characterized, IgM/κ light-chain-restricted LPL intimately coexisted with a phenotypically-related amyloidoma in the same anatomical site, without any evidence of systemic involvement by any other lymphomatous proliferations or amyloid deposition. Despite local recurrence after 1 month, likely related to a previous incomplete excision, both diseases remained confined to the first site of involvement, and the patient never developed systemic amyloidosis or lymphomatous spread during the follow-up period.

This is a peculiar and intriguing finding. From a clinical point of view, the lesion did not initially raise particular concern for a lymphomatous process. In characterizing the lymphoplasmacytic population itself, the clonality analysis by PCR favored a neoplastic process over a reactive, inflammatory one. Also, the demonstration of a typical immunophenotype with IgM/κ light-chain restriction alongside the canonical c.794T>C/p.L265P mutation in the MYD88 locus supported the final diagnosis of subcutaneous LPL. The immunophenotypic concordance between the lymphoma population and the tumor-like deposit of amyloid corroborated a causative relationship between them.

The relationship between amyloidosis and lymphoproliferative disorders is well-known, with the amyloidogenic protein consisting of aberrant Ig light chains produced by a variably systemic or localized plasmacytic-differentiated B-cell population capable of secretory activity. A systematic delineation of all possible combinations has been recently published by Stuhlman-Laeisz and colleagues [2]. A clonal lymphoplasmacytic proliferation-associated amyloidoma, however, is a rare encounter. Notably, to the best of our knowledge, only 3 examples of combined localized LPL and amyloidoma have been reported so far, all involving the central nervous system [3–5]. Another case that is worth mentioning has been described by Badell and colleagues [6], but in that case the patient had bilateral salivary gland infiltration with extension to the skin and a high serological burden, so we believe this cannot be considered a coherent example of localized LPL-associated amyloidoma.

No matter the classification of the amyloidoma-associated clonal lymphoplasmacytic proliferation, further systemic involvement does not occur. An interesting pathogenetic theory to explain this was proposed almost a decade ago by Per Westermark [7], who theorized a model of “suicidal neoplasm”. In his view, small aggregates of Ig light chains may be toxic to the plasma cells themselves, a paradoxical event controlling and eventually outgrowing the plasma cell clone. When prominent, amyloid deposits may overgrow the plasmacytic population, resulting in a “burned out plasmacytoma” [7]. This theory seems to fit perfectly with our case, in which we assumed that the growing massive deposition of amyloid had been progressively effacing the clonal, amyloid-producing lymphoplasmacytic proliferation.

From a clinical point of view, the challenge and first priority at time of diagnosis is to discriminate between a purely localized plasmacytic-differentiated B-cell lymphoma and a secondary infiltration by a systemic lymphoma, and to exclude systemic AL amyloidosis [2]. This inevitably translates into an extensive clinical, serological, and imaging workup to look for a potential, occult widespread systemic disease, as was the case for our patient. Afterwards, once the localized nature of both diseases has been established, a proportionate treatment should be selected. In our case, in the presence of a locally circumscribed, low-grade lymphoid neoplasm with absence of systemic amyloid burden, a local surgical approach was considered to be the appropriate first step, aiming at complete removal of the bulky amyloid lesion. Then, active surveillance seemed the most balanced option to deal with a localized, indolent lymphoma and monitor for possible progression to a systemic disease.

Conclusions

In summary, we have reported the clinical-pathological characteristics of a unique case of combined localized LPL and AL amyloidoma in the subcutis, without any evidence of systemic involvement. After thorough multidisciplinary staging, an active treatment aiming at local eradication of the disease followed by close follow-up proved to be effective for our patient.

Figures

References:

1.. Buxbaum JN, Dispenzieri A, Eisenberg DS, Amyloid nomenclature 2022: Update, novel proteins, and recommendations by the International Society of Amyloidosis (ISA) Nomenclature Committee: Amyloid, 2022; 29(4); 213-19

2.. Stuhlmann-Laeisz C, Schonland SO, Hegenbart U, AL amyloidosis with a localized B cell neoplasia: Virchows Arch, 2019; 474(3); 353-63

3.. Jagannathan G, Uppal G, Judy K, Curtis MT, Cerebral amyloidoma resulting from central nervous system lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma: a case report and literature review: Case Rep Pathol, 2018; 2018; 5083234

4.. Pace AA, Lownes SE, Shivane A, A tale of the unexpected: amyloidoma associated with intracerebral lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma: J Neurol Sci, 2015; 359(1–2); 404-8

5.. Ellie E, Vergier B, Duche B, Local amyloid deposits in a primary central nervous system lymphoma. Study of a stereotactic brain biopsy: Clin Neuropathol, 1990; 9(5); 231-33

6.. Badell A, Servitje O, Graells J, Salivary gland lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma with nodular cutaneous amyloid deposition and lambda chain paraproteinemia: Br J Dermatol, 1996; 135(2); 327-29

7.. , Localized AL amyloidosis: A suicidal neoplasm?: Ups J Med Sci, 2012; 117(2); 244-50

Figures

In Press

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943467

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250