24 September 2023: Articles

A Lethal Combination: Legionnaires’ Disease Complicated by Rhabdomyolysis, Acute Kidney Injury, and Non-Occlusive Mesenteric Ischemia

Unusual clinical course

Yuhei Fujisawa1ABCDEF*, Tatsuhito Miyanaga1E, Akari Takeji1E, Yukihiro ShirotaDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.940792

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e940792

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Legionnaires’ disease is one of the most common types of community-acquired pneumonia. It can cause acute kidney injury and also occasionally become severe enough to require continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT). Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) is a condition characterized by ischemia and necrosis of the intestinal tract without organic obstruction of the mesenteric vessels and is known to have a high mortality rate.

CASE REPORT: A 72-year-old man with fatigue and dyspnea was diagnosed with Legionnaires’ disease after a positive result in the Legionella urinary antigen test pneumonia confirmed by chest radiography and computed tomography. He developed acute kidney injury, with anuria, rhabdomyolysis, septic shock, respiratory failure, and metabolic acidosis. We initiated treatment with antibiotics, catecholamines, mechanical ventilation, CRRT, steroid therapy, and endotoxin absorption therapy in the Intensive Care Unit. Despite ongoing CRRT, metabolic acidosis did not improve. The patient was unresponsive to treatment and died 5 days after admission. The autopsy revealed myoglobin nephropathy, multiple organ failure, and NOMI.

CONCLUSIONS: We report a fatal case of Legionnaires’ disease complicated by rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney injury, myoglobin cast nephropathy, and NOMI. Legionella pneumonia complicated by acute kidney injury is associated with a high mortality rate. In the present case, this may have been further exacerbated by the complication of NOMI. In our clinical practice, CRRT is a treatment option for septic shock complicated by acute kidney injury. Thus, it is crucial to suspect the presence of NOMI when persistent metabolic acidosis is observed, despite continuous CRRT treatment.

Keywords: Acute Kidney Injury, Legionnaires' Disease, mesenteric ischemia, rhabdomyolysis, Male, Humans, Aged, Myoglobin, Shock, Septic

Background

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI), first reported in 1958, is a condition characterized by intestinal ischemia and irreversible necrosis, which occurs as a result of circulatory disturbance, but without arterial or venous occlusion [4]. While NOMI is commonly triggered by cardiac surgery or hypo-tension [5], diagnosing NOMI is challenging owing to the absence of characteristic symptoms, therefore delaying treatment initiation. This delay is concerning, as NOMI is a serious disease associated with a high mortality rate, despite multidisciplinary treatment that includes clinical therapy with vasodilators and surgical resection of the necrotic intestinal tract.

Here, we report a case of Legionnaires’ disease complicated by AKI, rhabdomyolysis, high lactic acid levels, and metabolic acidosis even after continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), which, upon autopsy, was found to be further complicated by NOMI.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented to our hospital with fatigue for 7 days and exertional dyspnea for 3 days. He had a history of smoking, but his drinking history was unknown. He reported going on a spa trip a week prior to the presentation. His medical history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and a stroke 10 years prior, which was treated with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. His medications included candesartan, amlodipine, and pitavastatin.

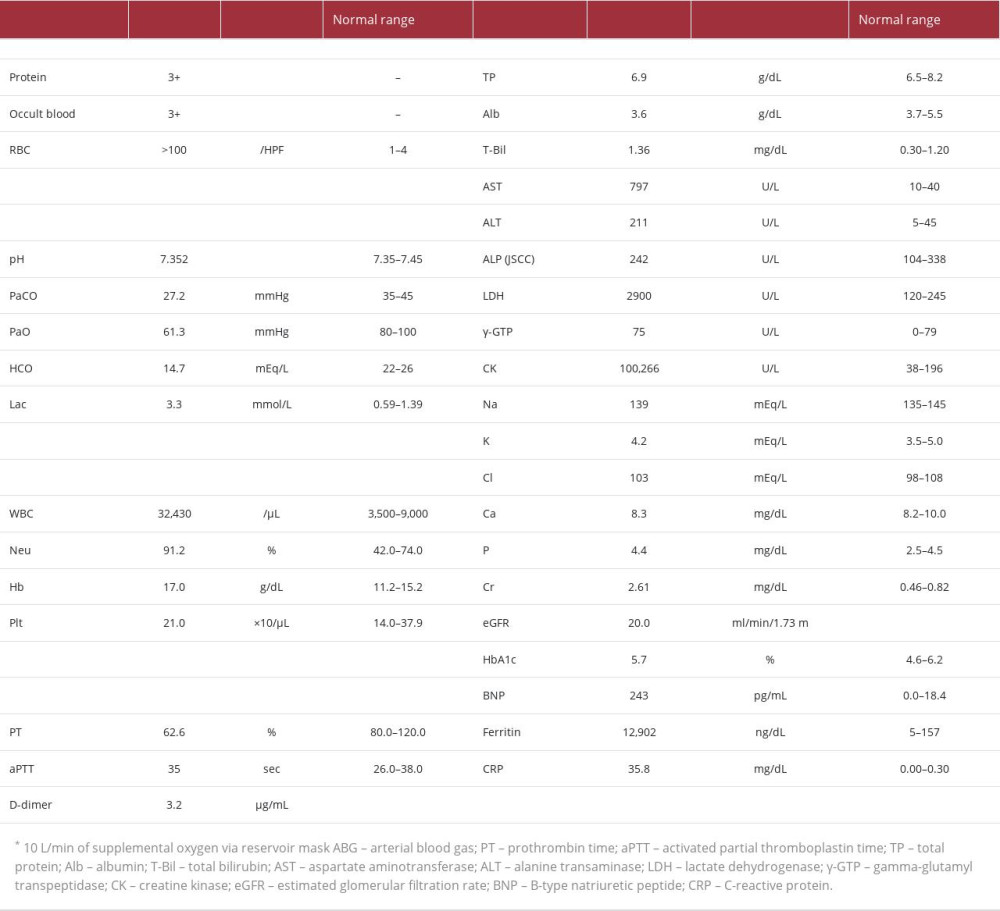

His vital signs on admission were as follows: temperature, 40.4°C; blood pressure, 140/92 mmHg; heart rate, 87 beats per min; respiratory rate, 40 breaths per min; and oxygen saturation, 93% after 10 L/min of supplemental oxygen via reservoir mask. Physical examination revealed weakened and diminished breath sounds on the right side but no crackles. His abdominal findings were unremarkable. There was no tenderness or muscular defense. The results of laboratory test results on admission are presented in Table 1.

Chest radiography revealed decreased permeability of the right lower lung fields. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest indicated extensive consolidation of the right lower lobe (Figure 1). An abdominal CT scan revealed neither intestinal edema nor ascites. The sputum and blood cultures were negative for significant pathogens. A

The patient was immediately intubated with mechanical ventilation, owing to severe hypoxia, and was administered levofloxacin, piperacillin/tazobactam, and steroid pulse therapy (methylprednisolone, 1000 mg/day). Six hours later, he was treated for septic shock with noradrenaline infusion because of the gradual worsening of his blood pressure.

On day 2, the patient developed anuria, and renal dysfunction worsened, with serum creatinine, blood urine nitrogen, and potassium levels of 6.4 mg/dL, 67 mg/dL, and 7.0 mEq/L, respectively. Metabolic acidosis also worsened, with a serum pH of 7.123, HCO3– levels of 15.2 mEq/L, and lactate levels of 2.9 mmol/L. CRRT was subsequently started.

On day 3, sputum examination by bronchoscopy was positive for Gimenez stain, and the culture was positive for

On day 4, the patient developed paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 71 000/uL), elevated fibrinogen degradation products (60 µg/mL), and was treated with a continuous infusion of heparin. The patient’s respiratory failure gradually worsened, with the progression of the pneumonia shadow on chest radiography (Figure 2).

On day 5 of hospitalization, despite continued CRRT, his metabolic acidosis persisted, and his blood pressure decreased further. The patient did not respond to the multidisciplinary treatment and died (Figure 3).

An autopsy was performed 12 h after death (Figure 4). Autopsy revealed pneumonia in the right lower lobe and diffuse alveolar damage during hyaline membrane formation in all lobes of both lungs. The autopsy also revealed cortical necrosis in the kidney and myoglobin cast in the distal tubules. Additionally, necrosis of the centrilobular tissue of the hepatic lobule, as well as of the adrenal gland, spleen, and pancreas, were observed. Non-contiguous necrosis, but no organic changes and thromboembolism, was observed throughout the small and large intestines. No vegetation was observed in the heart of the patient. Therefore, we definitively diagnosed Legionnaires’ disease, with myoglobin nephropathy, multiple-organ failure, and NOMI.

Discussion

Here, we report a case of Legionnaires’ disease with rhabdomyolysis and AKI in a patient who developed NOMI. Legionnaires’ disease was treated with antibiotics, severe respiratory failure was treated with mechanical ventilation, septic shock was treated with catecholamines and PMX-DHP, and AKI was treated with CRRT; however, his condition did not improve, and he died. The autopsy revealed diffuse alveolar damage, myoglobin cast nephropathy due to rhabdomyolysis, and NOMI.

A PubMed Mesh search using the terms “Legionella”, “autopsy”, and “adult” yielded 3 published cases after the year 2000 [6–8]. Most autopsy cases of

Legionnaires’ disease is sometimes associated with rhabdomyolysis or AKI, and kidney pathology reveals acute tubulointerstitial nephritis or myoglobin cast nephropathy. AKI due to Legionnaires’ disease is caused by rhabdomyolysis, the direct nephrotoxicity of

Although various adjunctive therapies have been introduced in addition to antimicrobial therapy, the prognosis of sepsis remains poor. A previous study showed improved life expectancy when PMX-DHP was administered at the start of CRRT for septic shock complicated with AKI [17]. However, Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines (SSCG) 2021 do not recommend the use of PMX-DHP for septic shock, given the insufficient evidence regarding improvement in life expectancy. In the present case, PMX-DHP for septic shock may not have been the right choice, given that it did not improve life expectancy, and it should either been avoided or administered simultaneously with CRRT on day 2. High-dose methylprednisolone was initiated to treat withdrawal from shock, but the patient died on day 5. It is impossible to determine whether the short-term steroid treatment significantly impacted on the patient’s death in a short time. However, given that SSCG2021 recommends a dose of 200 mg/day of hydrocortisone for treating withdrawal from septic shock [18], it may have been more beneficial to choose hydrocortisone with a fixed volume in this case rather than high-dose methylprednisolone.

There have been no previous case reports of Legionnaires’ disease associated with NOMI. NOMI has a very poor prognosis, with a mortality rate of 56% to 79% [5]. The most common risk factors for NOMI are cardiac surgery and hemodialysis [19]; other factors include heart failure, atrial fibrillation, advanced age, and catecholamine use [20–22]. NOMI usually presents with gradually worsening abdominal pain and no other typical symptoms. Laboratory findings include elevated CRP, AST, LDH, and lactase levels, as well as metabolic acidosis. None of the biochemical findings are pathognomonic for NOMI and should always be considered together with clinical symptoms for a comprehensive diagnosis [23]. In the present case, hemo-dialysis, advanced age, arrhythmia, sepsis, and catecholamines were considered risk factors for developing NOMI. At the time of admission, there were no concerns of abdominal findings, such as abdominal pain, and the abdominal CT scan showed no intestinal edema or ascites that were suggestive of NOMI. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed not to have NOMI. After admission, he was placed on a ventilator for acute respiratory failure and had decreased consciousness. Therefore, we were unable to confirm his subjective symptoms and occurrence of NOMI. Despite using CRRT for AKI, metabolic acidosis was not corrected, and lactate levels remained elevated. These 2 findings, together with the autopsy results, led us to speculate that the patient had developed NOMI during admission. However, diagnosing NOMI based on blood tests alone while the patient is alive is challenging because elevated AST, CK, and LDH levels can also occur in rhabdomyolysis. In this case, elevated lactate levels and prolonged metabolic acidosis, even with CRRT, were probably the only findings that led us to suspect the development of NOMI.

Conclusions

Here, we report a fatal case of Legionnaires’ disease complicated by rhabdomyolysis, AKI, myoglobin cast nephropathy, and NOMI. Legionella pneumonia complicated by AKI is associated with a high mortality rate, which may have been further exacerbated by the complication of NOMI. In our clinical practice, CRRT is a treatment option for septic shock complicated by AKI. Thus, it is crucial to suspect the presence of NOMI when persistent metabolic acidosis is observed, despite continuous CRRT treatment.

Figures

References:

1.. Fraser DW, Tsai TR, Orenstein W, Legionnaires’ disease: Description of an epidemic of pneumonia: N Engl J Med, 1997; 297; 1189-97

2.. Cunha BA, Burillo A, Bouza E, Legionnaires’ disease: Lancet, 2016; 387; 376-85

3.. Viasus D, Gaia V, Manzur-Barbur C, Carratalà J, Legionnaires’ disease: Update on diagnosis and treatment: Infect Dis Ther, 2022; 11; 973-86

4.. Ende N, Infarction of the bowel in cardiac failure: N Engl J Med, 1958; 258; 879-81

5.. Mishima Y, Acute mesenteric ischemia: Jpn J Surg, 1998; 18; 615-19

6.. Arinuma Y, Nogi S, Ishikawa Y: Intern Med, 2015; 54; 1125-30

7.. Kawashima A, Katagiri D, Kondo I, Fatal fulminant legionnaires’ disease in a patient on maintenance hemodialysis: Intern Med, 2020; 59; 1913-18

8.. Serio G, Fortarezza F, Pezzuto F, Legionnaires’ disease arising with hirsutism: Case report of an extremely confusing event: BMC Infect Dis, 2021; 21; 532

9.. Soni AJ, Peter A, Established association of legionella with rhabdomyolysis and renal failure: A review of the literature: Respir Med Case Rep, 2019; 28; 100962

10.. Shahzad MA, Fitzgerald SP, Kanhere MH, Legionella pneumonia with severe rhabdomyolysis: Med J Aust, 2015; 203; 399-400.e1

11.. Seegobin K, Maharaj S, Baldeo C, Legionnaires’ disease complicated with rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury in an AIDS patient: Case Rep Infect Dis, 2017; 2017; 8051096

12.. Buzzard JW, Zuzek Z, Alencherry BP, Packer CD, Evaluation and treatment of severe rhabdomyolysis in a patient with legionnaires’ disease: Cureus, 2019; 11; e5773

13.. Shah A, Check F, Baskin S, Legionnaires’ disease and acute renal failure: Case report and review: Clin Infect Dis, 1992; 14; 204-7

14.. Nishitarumizu K, Tokuda Y, Uehara H, Tubulointerstitial nephritis associated with Legionnaires’ disease: Intern Med, 2000; 39; 150-53

15.. Brewster UC, Acute renal failure associated with legionellosis: Ann Intern Med, 2004; 140; 406-7

16.. Shimura C, Saraya T, Wada H: J Clin Pathol, 2008; 61; 1062-63

17.. Iwagami M, Yasunaga H, Noiri E, Potential survival benefit of polymyxin B hemoperfusion in septic shock patients on continuous renal replacement therapy: A propensity-matched analysis: Blood Purif, 2016; 42; 9-17

18.. Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Surviving sepsis campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021: Crit Care Med, 2021; 49; e1063-e143

19.. Kühn F, Schiergens TS, Klar E, Acute mesenteric ischemia: Visc Med, 2020; 36; 256-62

20.. Bala M, Catena F, Kashuk J, Acute mesenteric ischemia: Updated guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery: World J Emerg Surg, 2022; 17; 54

21.. Klotz S, Vestring T, Rötker J, Diagnosis and treatment of nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia after open heart surgery: Ann Thorac Surg, 2001; 72; 1583-86

22.. Sato H, Nakamura M, Uzuka T, Kondo M, Detection of patients at high risk for nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia after cardiovascular surgery: J Cardiothorac Surg, 2018; 13; 115

23.. Bourcier S, Klug J, Nguyen LS, Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia: Diagnostic challenges and perspectives in the era of artificial intelligence: World J Gastroenterol, 2021; 27; 4088-103

Figures

In Press

21 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942921

22 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943346

24 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943560

26 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943893

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250