01 October 2023: Articles

A Case of Olanzapine-Induced Cutaneous Eruption

Challenging differential diagnosis, Unexpected drug reaction

Maninder K. Sohi1EF, Devin Towne2EF, Raja Mogallapu3EF*, Ankit Chalia3EF, Michael Ang-Rabanes3EFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.941379

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e941379

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Different medication classes have been implicated in cutaneous eruptions that may lead to significant morbidity and mortality. In drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, the patient may initially present with a cutaneous eruption and hematologic abnormalities which can lead to acute visceral organ involvement if the offending drug is not discontinued. There is also a potential for long-term sequelae such as autoimmune disorders.

CASE REPORT: A 47-year-old woman with an unknown past medical history and no known drug allergies was admitted to the Behavioral Health Unit, where she was diagnosed with disorganized schizophrenia and started on olanzapine. On day 17 of admission, she developed a diffuse, macular, and erythematous rash on her abdomen, which spread to involve over 50% of her total body surface area. Occipital and posterior auricular lymphadenopathy was present. The patient was treated with prednisone and diphenhydramine. Olanzapine was subsequently discontinued and the patient’s rash cleared up.

CONCLUSIONS: This case report highlights the challenges in diagnosing DRESS syndrome and the potential for antipsychotics to cause DRESS syndrome. DRESS syndrome is a clinical diagnosis augmented by laboratory tests with a wide range of patient presentations. Although there are probability criteria to assist with diagnosis, not all patients will fall exactly into these criteria, which can lead to missed diagnoses and poor patient outcomes. A challenge with DRESS syndrome diagnosis is the latency period between drug initiation and cutaneous eruption. Thus, in differential diagnoses for skin eruptions, temporal associations (minutes, days, weeks) with medications are crucial.

Keywords: Antipsychotic Agents, Drug Eruptions, Eosinophilia, olanzapine, Female, Humans, Middle Aged, Drug Hypersensitivity Syndrome, Exanthema, Disease Progression

Background

Many different medication classes have been implicated in cutaneous eruptions and can lead to significant morbidity and mortality if not recognized in a timely manner. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome is a cutaneous drug reaction that presents two to three weeks after exposure to the drug with a morbilliform, urticarial, or atypical targetoid eruption [1–4]. The cutaneous eruption has also been described as a maculopapular or erythematous rash in case reports of DRESS syndrome as noted in a literature review published in 2011 [5]. It should also be noted that onset can even begin up to six to eight weeks after drug exposure [2]. Medications commonly implicated in DRESS syndrome include anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin), allopurinol, vancomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and other antimicrobials [1,2]. Psychotropic drugs, including antipsychotics (clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine), have also been implicated in case reports [3]. Olanzapine, as will be discussed in this case report, is a second-generation (atypical) antipsychotic medication which works through D2 receptor antagonism and serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonism [6]. Although symptoms tend to resolve following drug discontinuation, there is high morbidity and mortality (estimated up to 10%) associated with DRESS syndrome along with possible long-term sequelae and recurrence of symptoms without re-exposure to the drug [1,2].

It has been noted that DRESS syndrome exists on a spectrum with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS) [1]. The pathophysiology of DRESS syndrome is not fully understood. However, it has been described as a delayed type IVb hyper-sensitivity reaction, and some have proposed the involvement of regulatory T cells and drug detoxication enzymes along with genetic factors and certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles [1,2,7,8].

Although DRESS syndrome is a clinical diagnosis augmented by laboratory (lab) tests such as complete blood count (CBC) with differential, liver function tests, kidney function tests, and urinalysis, different scoring systems have been developed that aid in diagnosis [7]. The European Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions to Drugs and Collection of Biological Samples (RegiSCAR) scoring system for identifying DRESS syndrome includes acute skin eruption suggestive of DRESS syndrome, fever (>101.3°F or >38.5°C), lymphadenopathy, systemic/internal organ involvement, atypical lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, time to symptom resolution (≥15 days), and exclusion of other potential causes (antinuclear antibody, blood cultures, hepatitis A, B, C serology, and Chlamydia/Mycoplasma pneumonia) [1,2,7]. Per this criterion, patient presentation can be divided into “definite,” “probable,” “possible,” or “excluded” case of DRESS syndrome [1,2,9]. Clinically, patients can also present with facial edema or anasarca [4]. Differential diagnoses should include Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), among other cutaneous drug reactions [2]. These differential diagnoses differ from DRESS syndrome in time to symptom onset from drug initiation, degree of visceral organ involvement, and histological features. As previously mentioned, DRESS syndrome can present two to eight weeks after drug exposure, whereas SJS and TEN present four to 28 days after drug exposure, and AGEP presents one to 11 days after drug exposure [2,10]. With SJS and TEN, patients having a blistering rash with skin detachment and positive Nikolsky’s sign (separation of the epidermis when lateral pressure is applied to the skin) along with the potential for multiorgan involvement (ears, nose, throat, etc.) and full-thickness epidermal necrosis on histology. AGEP presents with intertriginous erythema, pinpoint non-follicular pustules, positive Nikolsky’s sign in early stages of the disease course, and post-pustular skin desquamation in later stages, with rare systemic involvement, although it is possible [10].

Case Report

A 47-year-old woman with an unknown past medical history presented to the Emergency Department after being found walking alongside a highway. On presentation, the patient had a disorganized thought process and appeared to be responding to internal stimuli. She had limited insight along with a flat affect. She denied auditory or visual hallucinations. Her urine drug screen was negative on admission. She was admitted to the Behavioral Health Unit, where she was subsequently diagnosed with disorganized schizophrenia, which is a subtype of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia has a heterogenous clinical presentation of positive and negative symptoms that involve multiple domains of functioning, such as cognition, behavior, and emotion, with symptoms present for at least six months [11]. The patient had no known outpatient medications and no known allergies at the time of admission. She was started on olanzapine 10 mg/day by mouth, which was titrated to 15 mg/day on day 3 of admission and eventually to the maximum dose of 20 mg/day on day 9 of admission.

On day 17 of admission, the patient endorsed a rash that developed on her abdomen, which was macular in appearance, diffuse, and erythematous. The hospitalist was consulted on day 18 and subsequently started the patient on systemic prednisone 40 mg by mouth (tapering dose) and diphenhydramine 50 mg every 6 hours by mouth as needed for suspected “dermatitis.” By day 19 of admission, the rash had spread to involve the patient’s abdomen, bilateral upper extremities, bilateral popliteal fossa, back, neck, and face. The rash, at this point, was noted to involve over 50% of the patient’s total body surface area (TBSA). Bilateral lymphadenopathy was appreciated in both occipital and posterior auricular lymph nodes. The patient remained afebrile and denied pruritus, difficulty swallowing, or airway compromise. Vital signs remained stable during this time. She noted that the only new product introduced to her skin during admission was shaving cream.

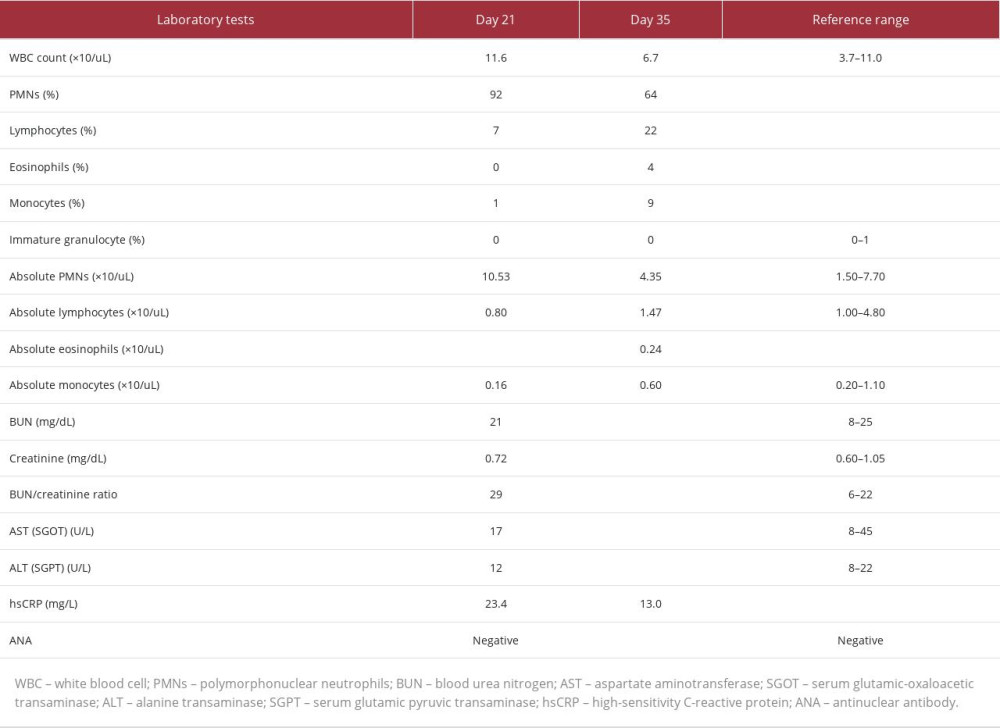

Given the rate and extent of the spread of the rash despite systemic prednisone use, a literature search for a possible association between the patient’s presentation and psychotropic medications was conducted. This yielded limited yet existent literature associating olanzapine with DRESS syndrome. It was then decided to prophylactically discontinue olanzapine on day 20 of admission and observe for response. On day 21 of admission, the patient’s rash began to clear up. Additionally appreciated on physical exam was decreased lymphadenopathy in occipital and posterior auricular lymph nodes. Pertinent lab tests completed on day 21 of admission are shown in Table 1, although this is not an exhaustive list of lab tests performed. When lab tests were rechecked on day 35, all previously checked lab tests apart from high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) were within normal limits, as shown in Table 1. A biopsy of the rash was not performed; thus, dermatopathology results are not available in this case. Of note, the patient’s oral temperature never rose above 37.1°C (98.4°F). Clinical photographs of the rash were not obtained for this patient.

Following the discontinuation of olanzapine, the patient was started on ziprasidone 20 mg twice daily by mouth. The prednisone taper was continued as the rash continued to resolve. By day 21 of admission, olanzapine was documented as a drug allergy in the patient’s medical record, with the comment of “DRESS syndrome” under reaction type.

Discussion

DRESS syndrome carries an overall population risk between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 10 000 drug exposures [2,3]. DRESS syndrome is a clinical diagnosis augmented by lab tests with a wide range of patient presentations [4,7]. Scoring criteria can aid providers in diagnosis as DRESS syndrome has a heterogenous clinical presentation of cutaneous eruption and visceral organ involvement with the potential for long-term sequalae. Fever (>38°C) is present in many patients and may even be one of the first presenting symptoms in addition to the cutaneous eruption [2,9]. DRESS syndrome has been associated with viral reactivation of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6),

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV), which can lead to worsening of the patient’s initial disease presentation and poor patient outcomes [1,2]. Despite this, diagnosis of DRESS syndrome in clinical practice is often overlooked, likely due to limited provider familiarity with this syndrome.

In this case report, the patient had an acute cutaneous eruption suggestive of DRESS syndrome, which involved over 50% of the TBSA and she had lymphadenopathy (at two sites). The patient’s lab test results are discussed below. When referring to the RegiSCAR scoring criteria for identifying DRESS syndrome, this case can be classified as possible DRESS syndrome, although it should be noted that different probability scales for DRESS syndrome may yield slightly different results. In this case, SJS and TEN were lower on the differential diagnoses list, as the patient’s rash did not blister and there was no skin detachment or desquamation. Also, the patient did not have mucosal involvement. The patient’s cutaneous eruption presented over two weeks (day 17 of admission) after drug initiation, thus making AGEP less likely, and the patient did not present with pinpoint pustules [10]. We also excluded acute contact dermatitis because the patient was not exposed to any new skin care products or detergents aside from shaving cream, which did not line up with the presentation of the rash. A viral or bacterial exanthem could also be considered in this case, but is less likely given that the patient remained afebrile during the hospital course and blood cultures were negative. Previous cases in the literature have noted that many times drug eruptions that are suggestive of DRESS syndrome may not completely meet the criteria, so some have termed this “mini-DRESS” to indicate a minor form of DRESS syndrome [4,5,12]. This terminology has not widely been accepted at this time and there continues to be debate regarding this topic due to not only the heterogeneity of presentation but also changes in disease course depending on the timing of clinician intervention [7].

Acute complications of DRESS syndrome include hematological abnormalities, along with liver, kidney, heart, and/or lung involvement. In this case, the lab tests drawn on day 21 of admission showed a mild increase in the white blood cell (WBC) count and an increase in the absolute polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs). Eosinophilia was not present. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (Cr) were within normal limits, although there was a very mild increase in the BUN/Cr ratio. Liver function tests that included aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) were within normal limits. No electrolyte derangements were noted at this time. Thus, these lab test results were not concerning for acute kidney or liver involvement. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was mildly elevated and sedimentation rate was within normal limits. Lab tests also showed negative antinuclear antibodies (ANA). Urine and blood cultures were negative, making an infectious process less likely. EKG showed normal sinus rhythm, making myocarditis or cardiac involvement less likely in this case, although troponins were not checked and an echocardiogram was not performed as the patient did not have any cardiac concerns at the time of rash presentation or thereafter.

Although the patient’s lab test results do not match the RegiSCAR scoring system, there are some potential reasons behind this. One important consideration in this case is that the lab tests were not drawn immediately after the skin eruption was first noted and when lab tests were drawn, the patient was on a systemic prednisone taper and as-needed diphenhydramine. Diphenhydramine may have suppressed eosinophilia, as the literature notes the role of antihistamines in enhancing apoptosis of eosinophils, which leads to decreased eosinophil survival [13]. Considering the patient’s hospital course in this case, further skin patch testing or lymphocyte transformation tests (LTTs) were not performed, as suggested in the literature [2]. It has also been noted that LTTs have limited sensitivity [2].

Prompt discontinuation of the offending drug is the crucial first step in management. Supportive measures along with topical or systemic corticosteroids are considered first-line treatment, which were implemented in this case, although the etiology of the skin eruption was not clear at that time [1,2]. One of the main goals is catching DRESS syndrome early in the disease course to prevent and minimize visceral organ involvement. This will also help to prevent or lessen the severity of the long-term sequelae that accompany DRESS syndrome, which include autoimmune disorders such as autoimmune thyroiditis, and diabetes mellitus. Thus, serial monitoring for these conditions is of utmost importance [1,4]. A challenge with DRESS syndrome diagnosis is the latency period between drug initiation and cutaneous eruption [1]. This temporal association may be particularly challenging with inpatient hospital admission where patients may be started on multiple new medications within a short time period. Differential diagnoses for skin eruptions must be broad and temporal associations (minutes, days, weeks) with medications must always be considered. In this case report, the patient’s rash had a temporal association not only with medication initiation and symptom development, but also with resolution of symptoms upon medication discontinuation.

DRESS syndrome must be considered a potential adverse effect when initiating psychotropic medications. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a Drug Safety Communication in 2016 for olanzapine, where they identified 23 cases of DRESS syndrome through the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) associated with olanzapine since it was first available in 1996 [14]. Previous case reports implicate clozapine, another second-generation (atypical) antipsychotic, as a cause of DRESS syndrome. Interestingly, the literature notes that clozapine-induced DRESS syndrome presents more often with visceral organ involvement, eosinophilia, and fever, and less often with a cutaneous eruption, which may be a reason this diagnosis is overlooked [15,16]. Another case report discussed DIHS/DRESS syndrome in a patient who started taking both olanzapine and lansoprazole while hospitalized; both medications were discontinued, but it was noted that the patient’s rash and fever were thought to be secondary to olanzapine-induced DIHS/DRESS syndrome. It was hypothesized that the patient was sensitized to olanzapine prior to hospitalization as he was taking the medication prior to admission, thus he developed a cutaneous eruption within ten days of restarting olanzapine [17]. Consequently, it is important to document this adverse reaction to the medication in the patient’s chart for future patient care. At this time, literature is not available on the reintroduction of olanzapine for patients with a history of DRESS syndrome; therefore, the risk associated with this is unclear, but the case report just described points toward potential sensitization and a quicker onset of symptoms from prior drug exposure. Given the high potential for complications and long-term sequelae along with the availability of alternative therapy, it may be more beneficial and safer for patients to continue with alternative therapy.

Conclusions

The case presented highlights the development of DRESS syndrome in the setting of olanzapine use in a female patient admitted for disorganized schizophrenia. Upon onset of the patient’s rash, the differential diagnosis was broad given the nonspecific physical exam findings and lab test results, a largely unknown past medical history including unknown allergies, and the diverse presentation of cutaneous eruptions. Providers should be aware of the not uncommon and potentially fatal consequence of DRESS syndrome when initiating a patient on a psychotropic medication. Given the limited familiarity with DRESS syndrome, there is reason to believe that the overall incidence of DRESS syndrome is underrepresented. A high index of suspicion is important, even when the patient presentation may fall slightly outside of probability criteria, which shows the importance of a clinical diagnosis in these cases. Future research on the association between psychotropic pharmacotherapy and DRESS syndrome would be beneficial in enhancing both provider awareness and patient outcomes.

References:

1.. Cardones AR, Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome: Clin Dermatol, 2020; 38(6); 702-11

2.. De A, Rajagopalan M, Sarda A, Das S, Biswas P, Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: An update and review of recent literature: Indian J Dermatol, 2018; 63(1); 30-40

3.. Penchilaiya V, Kuppili PP, Preeti K, Bharadwaj B, DRESS syndrome: Addressing the drug hypersensitivity syndrome on combination of Sodium Valproate and Olanzapine: Asian J Psychiatr, 2017; 28; 175-76

4.. Isaacs M, Cardones AR, Rahnama-Moghadam S, DRESS syndrome: Clinical myths and pearls: Cutis, 2018; 102(5); 322-26

5.. Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, The DRESS syndrome: A literature review: Am J Med, 2011; 124(7); 588-97

6.. Crismon M, Smith TL, Buckley PF, Schizophrenia: DiPiro’s pharmacotherapy: A pathophysiologic approach, 2023, McGraw Hill [Accessed July 11, 2023]

7.. Schunkert EM, Divito SJ, Updates and insights in the diagnosis and management of DRESS syndrome: Curr Dermatol Rep, 2021; 10(4); 192-204

8.. , DRESS syndrome: Remember to look under the skin: MEDSAFE Prescriber Update, 2011; 32(2); 12-13

9.. Mohammed R, Panikkar S, Elmalky M, Drug reaction, eosinophilia, and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome as a mimicker of spinal infection: Awareness for spinal surgeons: Cureus, 2020; 12(4); e7503

10.. Duong TA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, Chosidow O, Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs [published correction appears in Lancet. 2017;390(10106): 1948: Lancet, 2017; 390(10106); 1996-2011

11.. , Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders: In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 2022

12.. George C, Sears A, Selim AG, Systemic hypersensitivity reaction to Omnipaque radiocontrast medium: A case of mini-DRESS: Clin Case Rep, 2016; 4(4); 336-38

13.. Hasala H, Moilanen E, Janka-Junttila M, First-generation antihistamines diphenhydramine and chlorpheniramine reverse cytokine-afforded eosinophil survival by enhancing apoptosis: Allergy Asthma Proc, 2007; 28(1); 79-86

14.. , FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about rare but serious skin reactions with mental health drug olanzapine (Zyprexa, Zyprexa Zydis, Zyprexa Relprevv, and Symbyax), 2016

15.. de Filippis R, De Fazio P, Kane JM, Schoretsanitis G, Pharmacovigilance approaches to study rare and very rare side-effects: The example of clozapine-related DiHS/DRESS syndrome: Expert Opin Drug Saf, 2022; 21(5); 585-87

16.. de Filippis R, De Fazio P, Kane JM, Schoretsanitis G, Core clinical manifestations of clozapine-related DRESS syndrome: A network analysis: Schizophr Res, 2022; 243; 451-53

17.. Sogo A, Horiuchi H, Ueda T, Early-onset drug hypersensitivity syndrome in a man with pneumonia due to pre-sensitization to olanzapine: Cureus, 2022; 14(6); e26374

In Press

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942853

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942660

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943174

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943136

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250