27 November 2023: Articles

Excessively High Chronic Propranolol Overdose in Infantile Hemangioma: A Case Report

Management of emergency care

Heba Alshammari1BDE, Alhanouf Alessa1BEF, Yasmin Elsharawy1BEF, Ashjan Alghanem1EF, Abdullah M. AlhammadDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.941765

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e941765

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of childhood, occurring in approximately 5% of infants. Oral propranolol at 2 to 3 mg/kg daily is recommended for systemic treatment of high-risk infantile hemangiomas. Multiple propranolol formulations exist, and propranolol overdose can occur due to improper patient counseling. Propranolol acute toxicity in the pediatric population and its management are well described in the literature. However, data are lacking on chronic propranolol overdose and how to manage it, with the awareness that abrupt discontinuation of therapeutic doses of propranolol can lead to rebound sinus tachycardia.

CASE REPORT: A 7-month-old girl was prescribed a therapeutic dose of propranolol (1 mg/kg/day) to treat infantile hemangioma. However, due to an administration error, the patient received approximately 8 times the recommended dose (7.6 mg/kg/day for 2 months, then increased to 15.5 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks) and, surprisingly, remained asymptomatic. Her electrocardiogram was normal, and all routine laboratory tests were within the reference range. Propranolol was successfully tapered over 3 weeks by reducing the dose by 50% weekly until it reached the therapeutic dose. After tapering, the patient was asymptomatic, with a mild increase in hemangioma size. After 6 weeks of the therapeutic dose, the hemangioma was fading away.

CONCLUSIONS: This case is one of the few cases reported in the literature of high, chronic propranolol overdose in pediatric patients. The patient remained asymptomatic, and the overdose was successfully managed with gradual tapering over several weeks. This case report can serve as a guide in managing subsequent cases.

Keywords: Adrenergic beta-Antagonists, Drug Overdose, Hemangioma, Pediatrics, Propranolol

Background

Unintentional exposure to beta-blockers is common. In 2020, the American Association of Poison Control Center database reported 10 999 single-exposure cases of beta-blockers, and 1121 (9.6%) cases were coded to have moderate to major complications. Around 8761 (79.7%) of these exposures were unintentional [1]. From a retrospective study involving 5086 hospitalized poisoned patients, beta-blocker poisoning was identified in 5.1% of cases, and propranolol toxicity was the predominant presentation, accounting for 84.4% of beta-blocker poisonings [2].

Infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of childhood, occurring in up to approximately 5% of infants. Most infantile hemangiomas are usually small, self-limiting, and do not require treatment [3,4]. On the other hand, some are considered high-risk and will eventually require treatment. High-risk infantile hemangiomas include larger-size hemangiomas (more than 5 cm at any body location or more than 2 cm on the face or scalp). These can cause scarring, disfigurement, and structural abnormalities. Five or more hemangiomas can indicate hepatic hemangioma, congestive heart failure, and severe hypothyroidism [3]. Hemangiomas appearing on specific locations on the body can cause ulceration and disfigurement and are considered high-risk, for example, on the axillae, beard area, breast, neck, and nose. Hemangiomas near the eyes can affect vision, and hemangiomas near the lips can cause feeding impairment. Without structural abnormalities, oral propranolol at 2 to 3 mg per kg daily maintenance dose is recommended for systemic treatment of infantile hemangiomas as a first-line agent (strong recommendation, well-designed clinical trials, and systematic review by American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines) [3].

Absorption of propranolol after oral administration can vary due to different factors. Propranolol has complete absorption. However, only about 25% of the drug ultimately reaches the bloodstream due to extensive first-pass metabolism by the liver. In addition, it can be affected by a protein-rich diet and genetic variations [4,5]. Propranolol is the most lipophilic beta-blocker, easily crossing the blood-brain barrier and causing seizures in an overdose, which can be managed by giving benzodiazepines. Other manifestations of propranolol toxicity include hypotension, bradycardia, and dysrhythmias [4]. The toxic dose of acute propranolol ingestion in children is 4 mg/kg from immediate-release preparations and 5 mg/kg from sustained-release preparations [4].

Data on chronic propranolol overdose and management are lacking [4]. We report a case of excessively high, chronic propranolol overdose in a pediatric patient that was caused by dispensing different medication strengths and incorrect administration instructions.

Case Report

A 7-month-old baby girl (weight: 5.8 kg) presented to a dermatology clinic with infantile hemangiomas over the right thigh since birth. The hemangioma was large, measuring 7×4 cm. In the first dermatology appointment, she was initiated on topical timolol drops on the lesion. After 3 months (at the age of 10 months) and during the follow-up, there was only mild improvement in the hemangioma; therefore, oral propranolol 3.15 mg twice daily was recommended by the dermatologist. In the clinic, the patient was instructed to take 3.15 mL twice daily (this was based on the previous experience of the prescriber with a product concentration of (1 mg/1 mL). However, this product concentration was out of stock in our institution at the time of the prescription. The alternative product concentration was 40 mg/5 mL. For that, the patient was counseled by the pharmacist to take 0.4 mL twice daily, and the label instructions reflected this information. Despite that, the mother was given the medication as instructed in the clinic – initially 3.15 mL twice daily for 2 months then increased to 6.5 mL twice daily for 2 weeks of 40 mg/5 mL – instead of 0.4 mL and 0.8 mL twice daily. The mother confirmed that her child received the medication twice a day as scheduled, and the child was swallowing the whole dose without any complications. This overdose continued unintentionally for about 3 months. The event was discovered accidentally due to multiple early refills for propranolol. The parents were referred to the Emergency Department for further investigation and management. At the presentation, the patient looked well, active, and playful. The parents denied any history of hypo-activity or syncope; they noticed only that she sometimes became a little sleepy after doses.

Due to limited information published on chronic beta-blocker toxicity in pediatric patients, the Drug and Poison Information Center at our institution was involved in the management of this case. The emergency team diagnosed the case as a chronic asymptomatic unintentional propranolol overdose. The plan was to provide the patient with supportive management and monitoring. The patient was observed for 2 h and discharged home, as an electrocardiogram was normal and routine chemistry laboratory test results were within the reference range (including potassium level of 4.5 mmol/L [reference range, 3.5–5.1 mmol/L] and blood glucose level of 5.6 mmol/L [reference range, 3.3–5.6 mmol/L]).

The family was instructed and educated about the signs and symptoms of toxicity and appropriate dosing education. To avoid withdrawal symptoms and rebound sinus tachycardia, the dose was tapered gradually as follows:Current dose was 15.5 mg/kg/day (52 mg 6.5 mL twice daily).Decrease dose by 50%: 7 mg/kg/day (24 mg/3 mL twice daily) for 1 week.Then, decrease the dose by half: 3.5 mg/kg/day (12 mg/1.5 mL twice daily) for 1 week.Then, continue the dermatology team’s targeted dose of 2 mg/kg/day (6.5 mg/0.8 mL twice daily) until their clinic appointment.

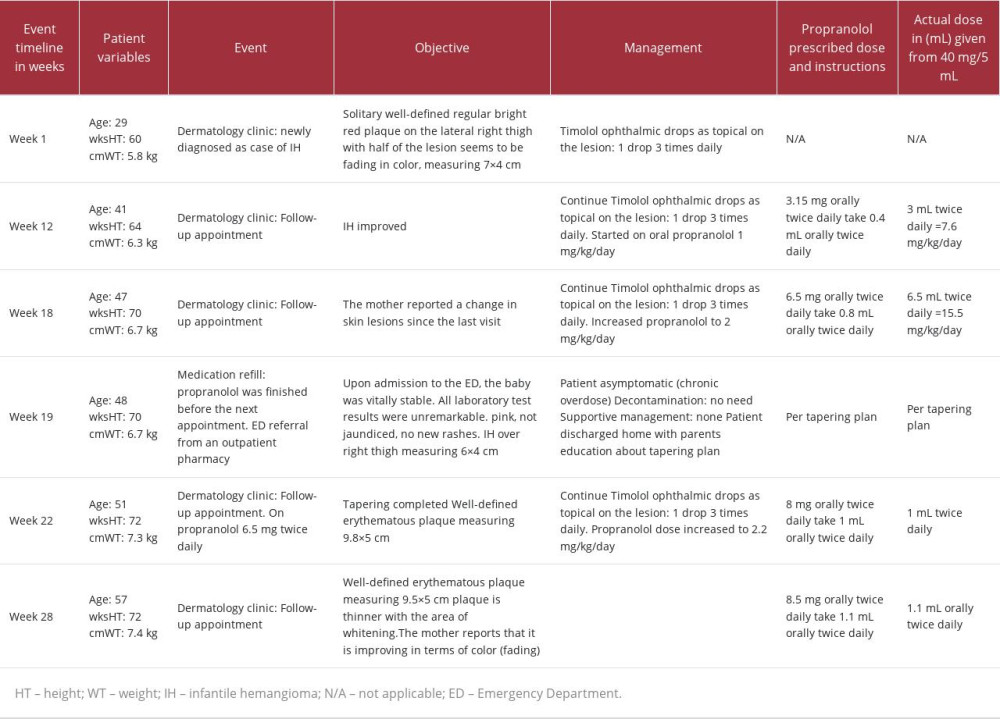

We instructed the parents to seek emergency medical attention during the tapering period if the patient experienced fainting, palpitations, dizziness, shortness of breath, and anxiety. The timeline for the events is illustrated in Table 1.

After tapering, there was a follow-up in the Dermatology Clinic. The tapering was successful, and the patient did not experience any symptoms during the tapering period. However, there was a mild increase in the hemangioma size. After 6 weeks of continuing the therapeutic dose, the mother reported an improvement in the color, and the hemangioma was fading away.

Discussion

We report the case of chronic propranolol overdose that was managed successfully with a gradual tapering off the drug to the recommended dose. Propranolol is considered the first-line treatment for infantile hemangiomas and has a good efficacy and safety profile [3]. The literature reported only minor adverse events with propranolol dosing up to 3 mg/kg/day for infantile hemangiomas [3]. There are many reported cases of acute propranolol intoxication in pediatric patients, and some cases were severe enough to require intensive care unit admission and medical intervention to sustain the patient’s life [6]. On the other hand, there are very limited reported cases of chronic propranolol overdose when compared with acute propranolol toxicity reports. Janmohamed et al reported the case of an 8-week-old baby with infantile hemangioma who mistakenly received 8 mg/kg/day for 1 month; the baby was asymptomatic, and the case was managed by decreasing the dose to 2 mg/kg/day [7]. To the best of our knowledge, our case has the highest reported propranolol chronic overdose, which reached up to 15.5 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks in patients with infantile hemangioma. Also, all the previously reported cases of chronic overdose lack important details, including how the propranolol was tapered.

If propranolol is ingested acutely in supratherapeutic doses, stopping the medication immediately will not be a problem. Nevertheless, in chronic exposure, holding the medication might predispose the patient to propranolol withdrawal phenomena due to increased sensitivity of the beta-adrenergic receptors [4]. Propranolol withdrawal phenomena can be manifested by headaches, sweating, palpitation, and an increase in blood pressure and heart rate [4]. Therefore, gradual tapering of beta blockers is recommended upon propranolol discontinuation. In adults, multiple studies support the gradual tapering of beta-blockers [4]. One study reported that a prolonged small dose of propranolol therapy before complete withdrawal would prevent the changes observed after abrupt withdrawal, such as increased blood pressure [8]. However, no such guidance exists in the pediatric population. The American Academy of Pediatrics and American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngology Vascular Anomalies Task Force Practice guidelines recommended tapering propranolol therapy upon discontinuation in infants with infantile hemangiomas. Still, no precise recommendation about the tapering schedule and duration was provided [3,9]. In a case series evaluating the response of 45 patients with infantile hemangiomas who discontinued propranolol therapy, with a mean treatment duration of 6.5 months (range, 3–11 months), propranolol was tapered over 2 weeks before complete discontinuation, with no reported adverse effects [10]. Fortunately, in our patient’s case, after 6 weeks of propranolol tapering, no rebound growth of infantile hemangiomas was noted. Therefore, in view of the limited evidence, a tapering schedule over 2 to 3 weeks may be advised before complete discontinuation, as reported in our case.

The American Association of Poison Control Centers reported more than 10 000 annual poison center calls related to units of measurement confusion [11]. Similarly, as reported in our case, the parents were instructed to administer the medication based on milligrams per dose; however, the parents misunderstood this instruction to be administered in milliliters, which resulted in administering supratherapeutic doses. Therefore, additional efforts and awareness should be directed toward enhancing the use of appropriate units of measurement when instructing patients to take liquid medications.

Conclusions

Case reports of chronic propranolol overdose in the literature are rare. This case represents the highest chronic overdose of propranolol documented in the scientific literature involving a pediatric patient, in which the patient exhibited sustained asymptomatic status. The successful management of this overdose was achieved through a systematic tapering regimen spanning several weeks. This case report can serve as a valuable reference for informing the approach to managing similar cases in the future.

Tables

Table 1.. Case summary.

References:

1.. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC, 2020 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 38th Annual Report: Clin Toxicol (Phila), 2021; 59(12); 1282-501

2.. Eizadi-Mood N, Adib M, Otroshi A, A clinical-epidemiological study on beta-blocker poisonings based on the type of drug overdose: J Toxicol, 2023; 2023; 1064955

3.. Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas: Pediatrics, 2019; 143(1); e20183475

4.. , Propranolol: In Depth Answers [database on the internet], 2023, Greenwood Village (CO), IBM Corporation [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Available from: www.micromedexsolutions.com

5.. Nagele P, Liggett SB, Genetic variation, β-blockers, and perioperative myocardial infarction: Anesthesiology, 2011; 115(6); 1316-27

6.. Belson MG, Sullivan K, Geller RJ, Beta-adrenergic antagonist exposures in children: Vet Hum Toxicol, 2001; 43(6); 361-65

7.. Janmohamed SR, Madern GC, de Laat PC, Oranje AP, Haemangioma of infancy: Two case reports with an overdose of propranolol: Case Rep Dermatol, 2011; 3(1); 18-21

8.. Rangno RE, Nattel S, Lutterodt A, Prevention of propranolol withdrawal mechanism by prolonged small dose propranolol schedule: Am J Cardiol, 1982; 49(4); 828-33

9.. Parikh SR, Darrow DH, Grimmer JF, Propranolol use for infantile hemangiomas: American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngology Vascular Anomalies Task Force practice patterns: JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2013; 139(2); 153-56

10.. Hong P, Tammareddi N, Walvekar R, Successful discontinuation of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas of the head and neck at 12 months of age: Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 2013; 77(7); 1194-97

11.. Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, 2011 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 29th annual report: Clin Toxicol, 2012; 50(10); 911-1164

Tables

In Press

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943467

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943376

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250