12 January 2024: Articles

A Unique Case of Caroli Disease in Kenya’s Medical Landscape

Mistake in diagnosis, Rare disease, Clinical situation which can not be reproduced for ethical reasons

Timothy Lengoiboni1ABCDEF*, Leway Kailani2ACDF, Maureen K. Bikoro3ABCDEF, Michael M. Mudeheri4ABCDEFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942019

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e942019

Abstract

BACKGROUND: If a young patient presents with fever, abdominal pain, jaundice and significant imaging abnormalities, especially dilation of the biliary system, it is usually due to obstruction from stones or strictures. However, on very rare occasions, it can be due to complications of congenital cystic dilatation of the biliary system, known as Caroli disease. We present such a patient and discuss the differential diagnosis and implications for long-term management.

CASE REPORT: A 14-year-old boy presented to the Emergency Department with a sudden onset of high-grade fever and abdominal pain for 2 weeks, accompanied by vomiting of blood. The patient had no relevant medical history. He was malnourished and had moderate pallor, jaundice, and right upper quadrant pain. Imaging revealed cystic dilatation of intrahepatic ducts and a central dot sign. There were no features suggesting advanced liver disease otherwise, and no tumors or cysts in the kidneys. A diagnosis of Caroli disease was made. The symptoms were ascribed to acute cholangitis and improved with antibiotics. He was discharged home 1 week later. No further blood loss was observed.

CONCLUSIONS: This case study describes a patient with ascending cholangitis, a complication of Caroli disease. This diagnosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when a child or young adult presents with features of cholangitis, abnormal biliary imaging, and/or upper gastrointestinal bleeding, or portal hypertension. No prior cases of this disease have been encountered, documented, or published in Kenya. This case can increase awareness among primary care clinicians, including pediatricians.

Keywords: Caroli Disease, Cholangitis, Cholangiocarcinoma, Jaundice

Background

Caroli disease is a rare congenital disorder presenting in childhood and/or early adulthood and one of a group of diseases with the umbrella term fibropolycystic liver disease [1–3]. All these disease variants are associated with congenital malformation of the ductal plate. Caroli disease is the type characterized by saccular or cystic widening of intrahepatic ducts, as seen on imaging and histopathology findings [1,3,4], and is inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion in most cases [3,4]. When congenital hepatic fibrosis accompanies the dilatation of the hepatic ducts, it is known as Caroli syndrome and is even more rare than the disease [1,3].

In 1958, Jacques Caroli first described Caroli disease as saccular or fusiform cystic dilatation in a segment of the liver that involves the larger bile ducts in the liver alone either in a focal or multifocal manner. This is associated with an increased incidence of biliary stones, hepatic abscesses, and at least in early stages, cholangitis with the absence of portal hypertension or cirrhosis, and association of dilated renal tubules or renal cysts [3]. The disease usually remains asymptomatic but when it is symptomatic, 80% of patients present in early adulthood with episodes of cholangitis, portal hypertension, or hepatomegaly [4,5]. Fever without obvious cause can precede clinical cholangitis and delay a diagnosis.

Diagnosis of Caroli disease is made when dilated liver cysts are shown to be connected to part of the biliary system using ultrasound, computerized tomography (CT) scan, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography [4–6]. The presence of a so-called “central dot sign” strongly supports the diagnosis. Non-invasive diagnostic procedures rather than invasive procedures are preferred, and direct cholangiography (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography) should only be undertaken by those who are also able to do interventions (stone/debris removal), because further contamination of the system without drainage can be detrimental by inducing worsening of cholangitis. If available, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography after ultrasound, which has less radiation exposure, is preferred over CT, certainly also in children.

Biopsy is not recommended in those who have hepatomegaly and features of portal hypertension but no features of biliary dilatation or renal disease on imaging studies [6]. Complications of Caroli disease include intractable cholangitis, secondary biliary fibrosis/cirrhosis, which can present as esophageal varices and portal vein thrombosis, and the development of cholangiocarcinoma, which is seen in other types of chronic inflammatory bile duct diseases, such as recurrent pyogenic fever, parasitic infestations of the biliary tract, and primary sclerosing cholangitis [4,5].

Differential diagnosis for Caroli disease includes polycystic liver disease (multiple simple cysts, not connected with the biliary system, often also in kidneys and/or pancreas) and liver abscess and usually can be differentiated with cross-sectional abdominal imaging (CT and ultrasound).

Therapeutic interventions focus mostly on the control of cholangitis. They can be given intermittently or sometimes as maintenance antibiotic therapy. Patients can benefit from cleaning of the biliary system from recurring debris and stones that predispose to bouts of cholangitis [7]. Depending on the specific features (one-sided disease or involvement of the whole biliary system) partial hepatectomy should be considered, and for some patients, the only option will be liver transplantation. Cholangiocarcinoma can be difficult to detect in patients with advanced disease. This case report reminds clinicians that Caroli disease can be asymptomatic till late childhood or early adulthood.

Case Report

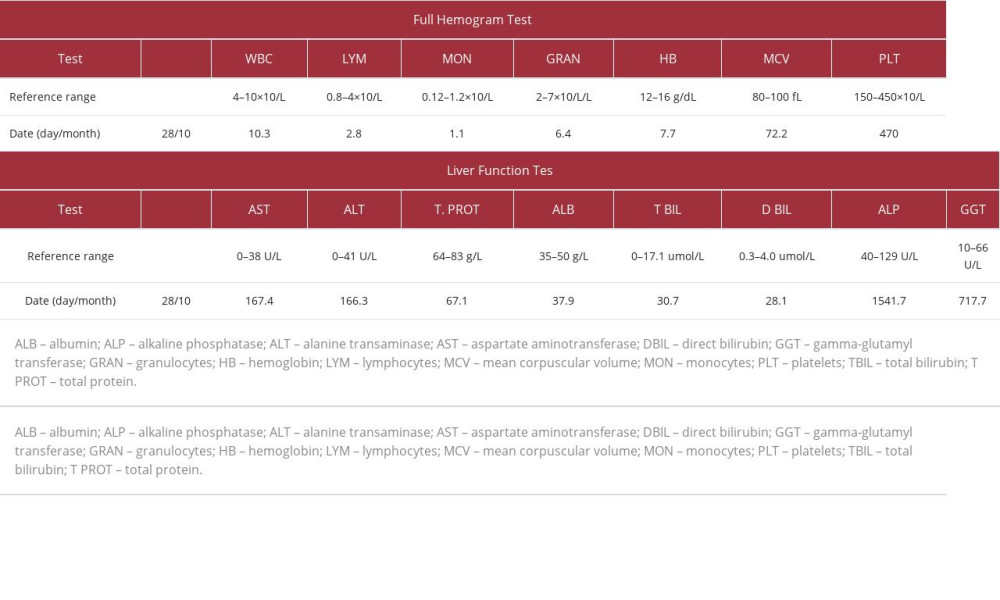

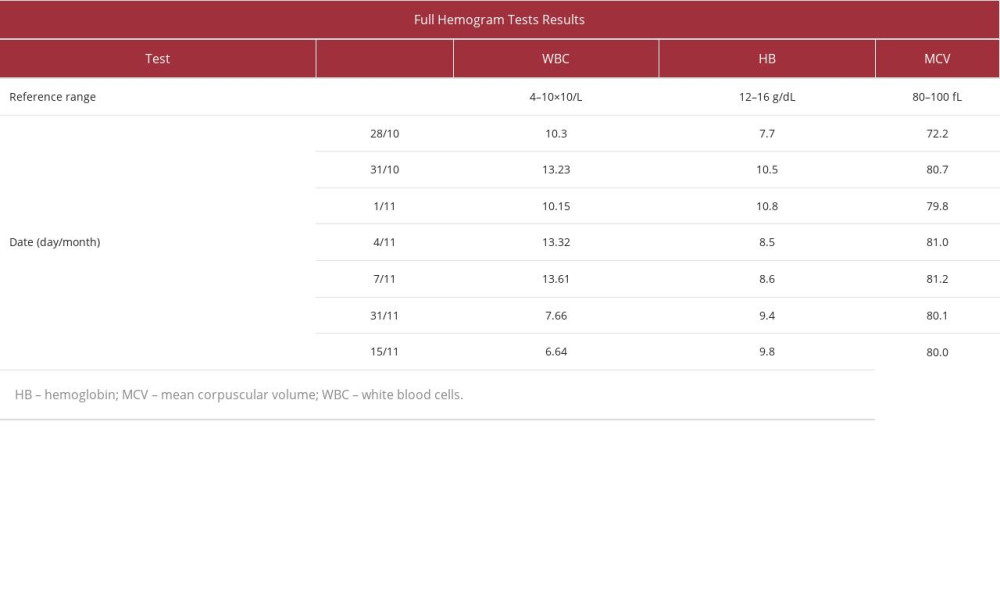

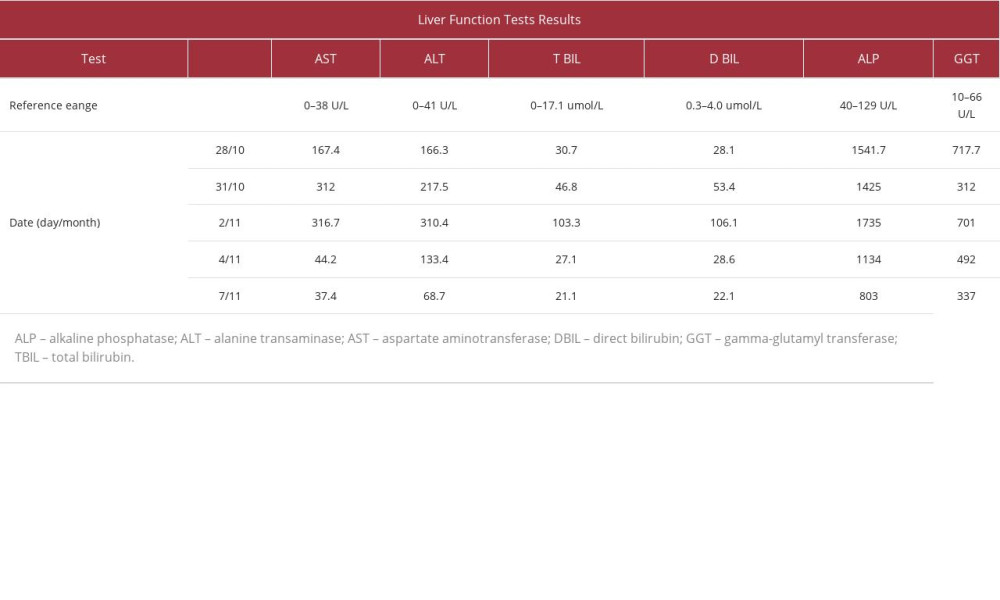

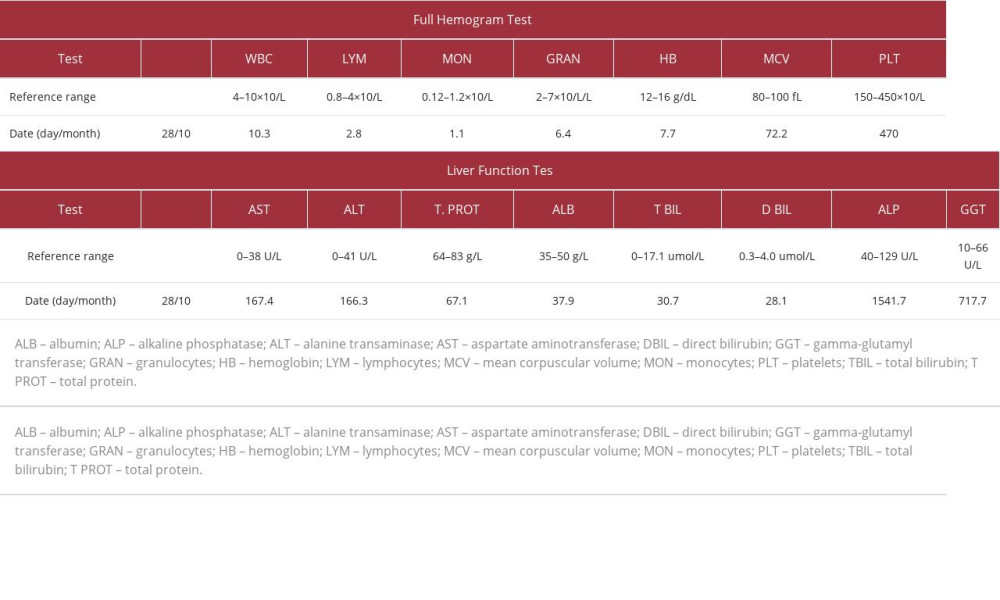

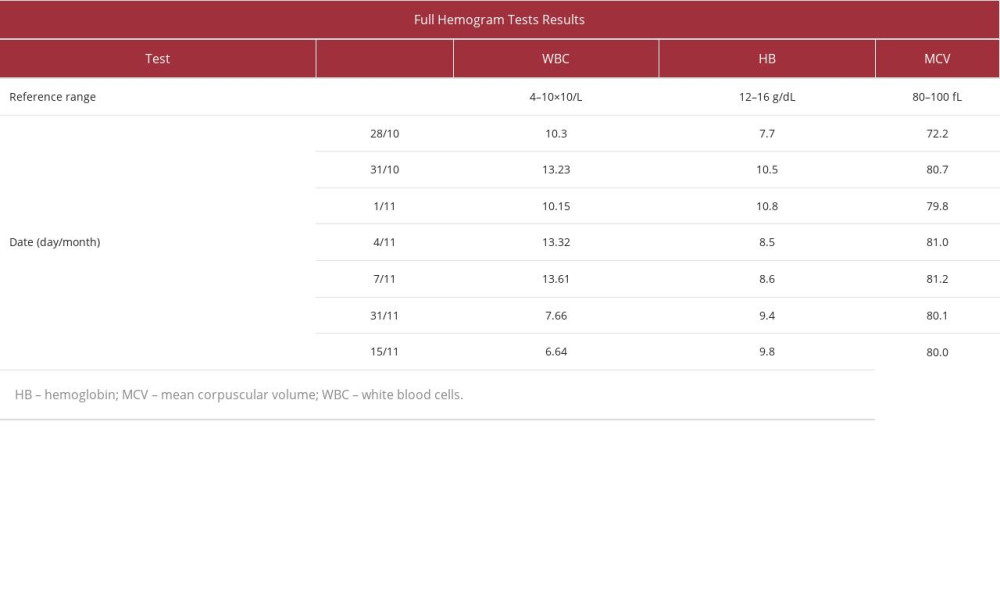

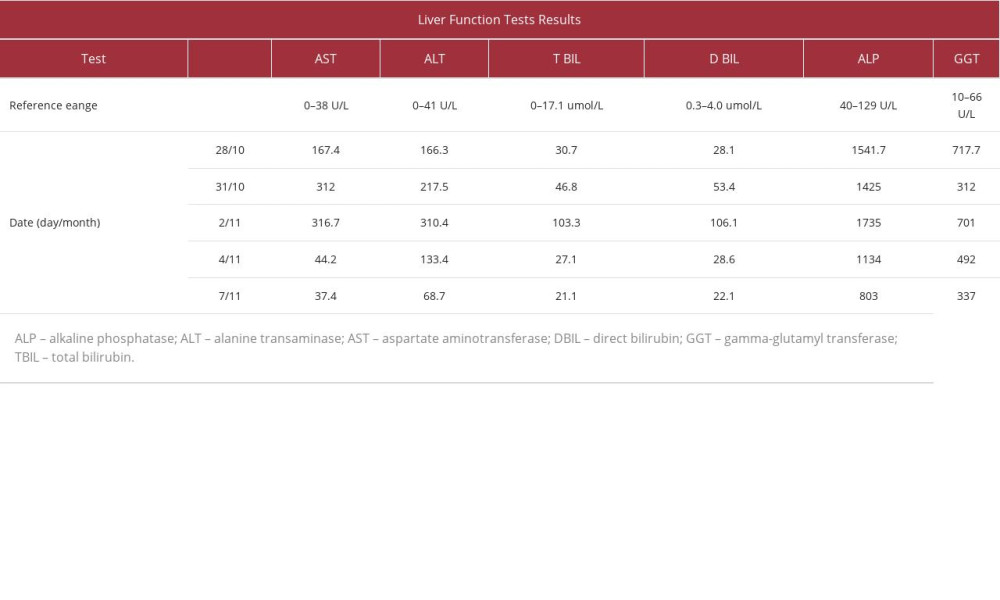

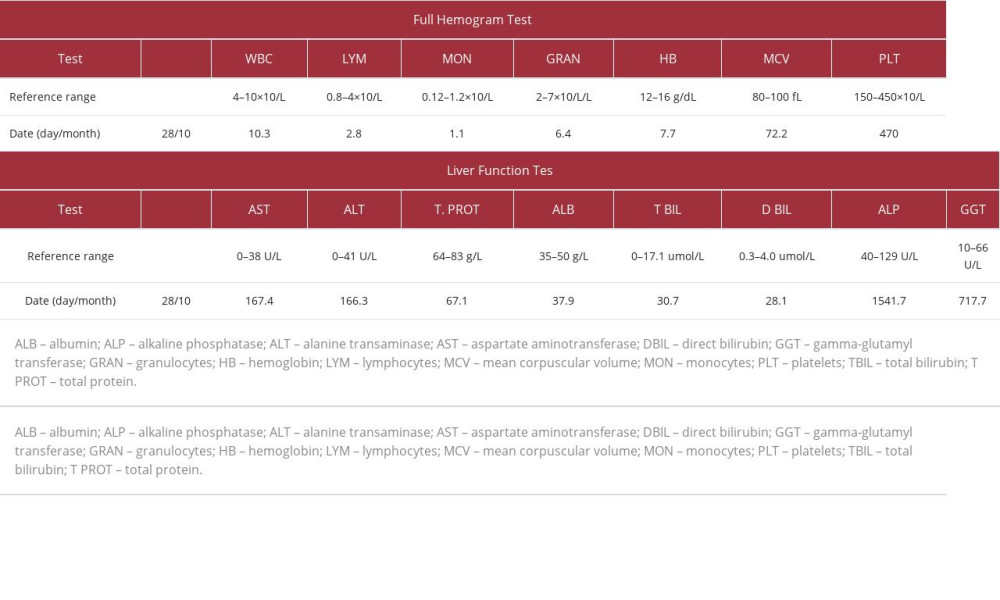

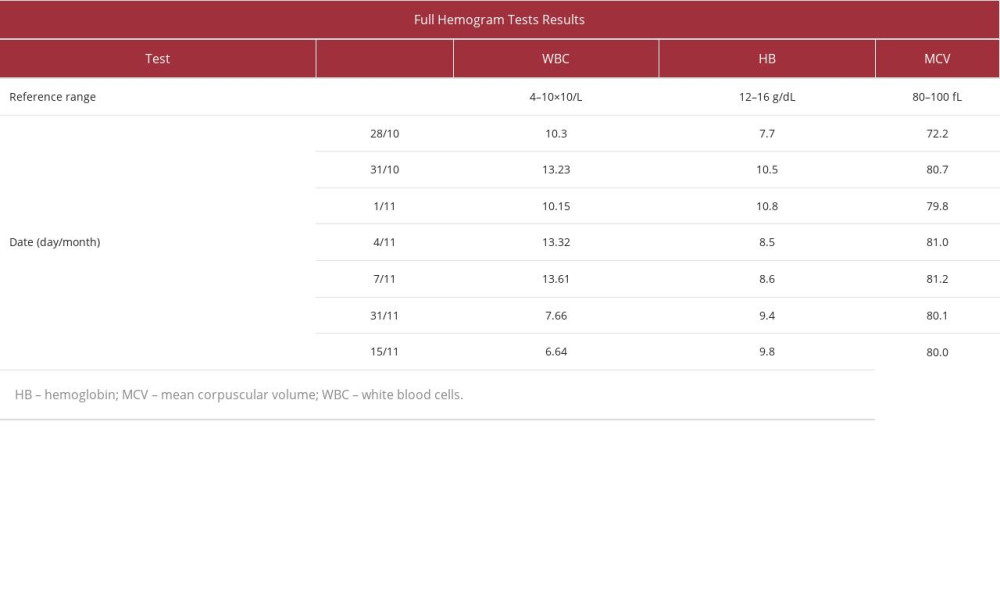

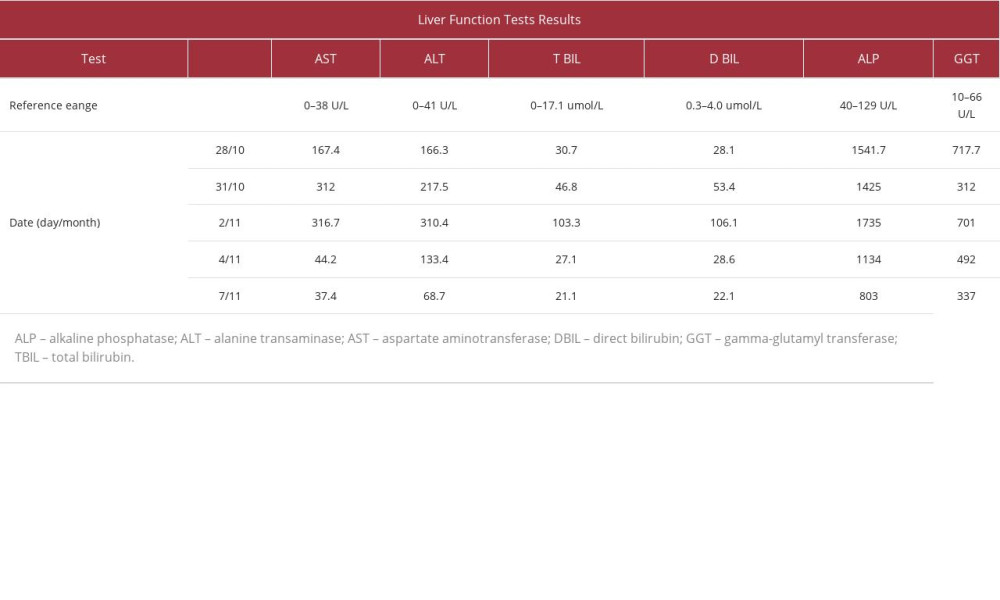

A 14-year-old Kenyan boy presented to the Emergency Department with abdominal pain for 2 weeks, mostly in the right hypochondrium, vomiting, fevers, and 1-day history of hematemesis. His medical history was unremarkable, with no prior admissions, and he had no history of recurrent fevers. There was no consanguinity suggested by the family history, and there was no history of any chronic illness or Caroli disease. Vital signs included a temperature of 38.7°C, blood pressure of 102/53 mmHg, heart rate of 79 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 92% on room air. On physical examination, he appeared malnourished, mildly pale, and jaundiced. He had right-sided hypochondrial pain but no rebound tenderness or Murphy sign. The liver was tender, with a span of 16 cm. Cardiac, respiratory, and nervous system examinations were normal. The laboratory findings at the Emergency Department before admission are shown in Table 1. The results showed moderate microcytic anemia and thrombocytosis, suggestive of iron deficiency anemia, as well as leukocytosis. He was admitted to the Medical Ward and treated with piperacillin-tazobactam, providing broad coverage against gram-positive and gram-negative organisms and anaerobes to treat the ascending cholangitis secondary to Caroli disease. All symptoms improved. There was no further hematemesis. Abdominal ultrasound and CT scan of the abdomen showed multiple cystic dilatations of the liver and prominent dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts. The CT scan showed an obvious central dot sign, and no renal cysts were seen (Figure 1). Based on the findings of the imaging, a diagnosis of Caroli disease complicated by ascending cholangitis was made. A repeat ultrasound scan was done after the resolution of the infection, which confirmed the presence of multiple cystic dilatations in the liver that were connected to dilated intrahepatic ducts, reconfirming the diagnosis (Figure 2). A complete blood count revealed a total white blood count of 13.3×109/L, hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL with a mean corpuscular volume of 80.7, and platelet count of 666×109/L (Table 2). Liver function tests revealed an aspartate aminotransferase level of 167.4 U/L, alanine transaminase of 166.3 U/L, total bilirubin of 30.7 mg/dL, direct bilirubin of 28.1 mg/dL, gamma-glutamyl transferase of 717.7, and alkaline phosphatase of 1541.7 (Table 3). Blood culture on admission to the ward did not grow any microorganisms. Results for anti-hepatitis C antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, and HIV rapid tests came back negative. The patient recovered, as evidenced by the resolution of the Charcot triad and hepatomegaly, as well as improving counts seen on the full hemogram and liver function tests. He was discharged from the hospital after 1 week. He was advised to continue taking metronidazole for another 5 days after discharge and finally left the hospital 2 weeks after the initial admission. The iron deficiency anemia was believed to be due to malnutrition/inadequate intake or from a Mallory Weiss lesion rather than from bleeding related to portal hypertension or esophageal varies. Endoscopy was deferred at this time.

Iron deficiency anemia is common in children in Kenya, with a prevalence of 26.9% [8], and there were no features of fibrosis of the liver on imaging of our patient. The patient was discharged with supplementary oral iron with a plan to follow up in the Outpatient Clinic. He will need life-long monitoring for the development of complications, specifically cholangiocarcinoma.

A CT scan was requested for the boy, despite his young age, to better visualize the pathology in the liver, which the abdominal ultrasound was not able to show. The amount of radiation from the CT scan machine was 110kV per slice, with slices of 5 mm thickness.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) would also have shown the pathology but it is more costly, and the boy was paying out of pocket as he had no health insurance. MRI features of Caroli disease include dilated hepatic ducts and the central dot sign within them [9,10].

Discussion

We reported a case of Caroli disease in a child who presented with abdominal pain, fever, and suspected upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. He was treated for cholangitis due to Caroli disease which was clinically diagnosed based on imaging, including the central dot sign found on a CT scan of the abdomen. This presentation is a typical presentation of Caroli disease, and the patient became symptomatic at the usual age, between adolescence and early adulthood. The findings of this case report are similar to those of a study done by Sun et al in China, in which Caroli disease was diagnosed in a 13-year-old boy who presented with recurrent fever for 1 month [11], and those of a study done by Abdullatif et al in Yemen, in which Caroli disease was diagnosed in a 16-year-old girl with chronic abdominal pain, low-grade fever, and recurrent jaundice who was repeatedly hospitalized for abdominal pain, without resolution [12]. Unlike the patient in that study, our patient was a boy, in keeping with the epidemiological findings of the disease that it is more common in males than females.

Similar findings were observed at Cocody Teaching Hospital of Abidjan by Ouattara et al in Cote D’Ivoire, where a 9-year-old girl presenting with intermittent chronic fever, hepatomegaly, and ascites without abdominal pain or jaundice was diagnosed with Caroli disease [13].

The laboratory findings at presentation to the Emergency Department were consistent with cholangitis, which is usually caused by ascending anaerobic organisms or gram-negative organisms or a mixture as a complication of biliary stasis caused by dilated bile ducts; cholangitis is the most common cause of hospital admission in patients with Caroli disease. The development of cholangitis results in diminished quality of life, signifying poor long-term prognosis for the boy [14].

Characteristic imaging findings in Caroli disease, as seen using the various imaging methods, are hepatic cysts that are shown to be in continuity with dilated intrahepatic ducts and the central dot sign [5,15].

The central dot sign seen on cross-sectional imaging (CT or MRI) is highly suggestive but not pathognomonic of Caroli disease. It appears as a dark round area (cysts) inside the liver, inside which a whitish dot is seen, representing the complete surrounding of contrast within the portal vein branch by abnormally dilated bile ducts, and the dark area must be continuous with the rest of the bile ducts for a diagnosis of Caroli disease to be established [16].

Although the central dot sign is also seen in other conditions (peribiliary cysts, periportal lymphedema, and biliary obstruction), it helps differentiate Caroli disease from other conditions such as primary sclerosing cholangitis and recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, which also present with intrahepatic bile duct dilatation [17].

Caroli disease can also be proven genetically by demonstrating the presence of the PKHD1 gene, whose mutation codes for the production of abnormal fibrocystic protein in the liver and kidneys [11,18]. Such testing is usually costly and often not an option in low-income countries.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound has a role in the diagnosis of Caroli disease in young patients and children, in whom it shows dilated hepatic ducts surrounding portal radicles and is useful in detecting any malignant changes that can occur during follow-up [19].

MRI is a better diagnostic modality for Caroli disease, where it shows dilated intrahepatic ducts and the dot sign, like in a CT scan [6,20,21].

Caroli disease management involves the treatment of cholangitis with antibiotics and interventions including the repeated removal of debris/stones from the biliary system. Long-standing poorly controlled disease can evolve into biliary fibrosis/cirrhosis [6,15]. Such patients and those who have co-existing congenital hepatic fibrosis may need to be treated for sequelae of portal hypertension, such as varices [6,15]. Additional management modalities include surgical removal of localized disease and liver transplantation [6,11,15,22].

In terms of long-term risk, and unlike polycystic liver disease with a low if any risk of cholangiocarcinoma, the major risk of chronic biliary tract infection in Caroli disease, just as in choledochal cysts, is the development of cholangiocarcinoma, which occurs a hundred times more frequently in these patients than in the general population, thus the importance of following these patients after discharge [5]. Unfortunately, the diagnosis can be challenging. A retrospective German multicenter study reported a cholangiocarcinoma prevalence among patients with Caroli disease and Caroli syndrome of 7.1% (6.6–7.3%) which was similar to a study done by Dayton et al in 1983 [23].

Conclusions

Caroli disease has low incidence rates, making it easy to escape diagnosis or be misdiagnosed, and should be considered as a possible cause of ascending cholangitis, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and portal hypertension in young patients. Abdominal pain is common in children, and non-specific abdominal pain in a setting of abnormal liver tests should raise the suspicion of Caroli disease for the examining clinician.

Various imaging modalities can be used to diagnose Caroli disease in children, including ultrasound, CT, MRI, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, hepatobiliary scintigraphy, and the invasive modalities of percutaneous cholangiography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [15,20]. The criterion standard for identifying Caroli disease is endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [6].

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Table showing both the complete blood count (full hemogram) and the liver function test results at the Emergency Department before admission. Values in red are outside the reference range. Table 2.. Table showing all complete blood count (full hemogram) results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range.

Table 2.. Table showing all complete blood count (full hemogram) results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range. Table 3.. Table showing all liver function test results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range.

Table 3.. Table showing all liver function test results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range.

References:

1.. Lewis J, Pathology of fibropolycystic liver diseases: Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken), 2021; 17(4); 238-243

2.. Umar J, Kudaravalli P, John S: Caroli Disease, 2023, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513307/

3.. Desmet VJ, Congenital diseases of intrahepatic bile ducts: variations on the theme “ductal plate malformation”: Hepatology, 1992; 16(4); 1069-83

4.. Acevedo E, Laínez SS, Cáceres Cano PA, Vivar D, Caroli’s syndrome: An early presentation: Cureus, 2020; 12(10); e11029

5.. Sultan MI, Pediatric Caroli Disease: Medscape (internet) Oct 20, 2017 https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/927248-overview

6.. Ananthakrishnan AN, Saeian K, Caroli’s disease: Identification and treatment strategy: Curr Gastroenterol Rep, 2007; 9(2); 151-55

7.. van den Hazel SJ, Speelman P, Tytgat GN, Role of antibiotics in the treatment and prevention of acute and recurrent cholangitis: Clin Infect Dis, 1994; 19(2); 279-86

8.. Oyungu E, Roose AW, Ombitsa AR, Anemia and iron-deficiency anemia in children born to mothers with HIV in Western Kenya: Glob Pediatr Health, 2021; 8; 2333794 X21991035

9.. Guy F, Cognet F, Dranssart M, Caroli’s disease: Magnetic resonance imaging features: Eur Radiol, 2002; 12(11); 2730-36

10.. Rivas A, Epelman M, Danzer E, Prenatal MR imaging features of Caroli syndrome in association with autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: Radiol Case Rep, 2018; 14(2); 265-68

11.. Sun J, Wang S, Chen B, Childhood-onset Caroli’s disease as a cause of recurrent fever: A case report: Front Pediatr, 2022; 10; 903285

12.. Almohtadi A, Ahmed F, Mohammed F, Caroli’s disease incidentally discovered in a 16-years-old female: A case report: Pan Afr Med J, 2022; 41; 204

13.. Ouattara A, Kone S, Allah-Kouadio E, Caroli disease: A case report observed at the Cocody Teaching Hospital of Abidjan (Cote D’Ivoire): Open J Gastroenterol, 2017; 7; 28-31

14.. Yonem O, Bayraktar Y, Clinical characteristics of Caroli’s syndrome: World J Gastroenterol, 2007; 13(13); 1934-37

15.. Suchy FJ, Caroli disease: UpToDate Apr 5, 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 19]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/caroli-disease#H855304549

16.. Botz B, Shoyab M, El-Feky M, Central dot sign Reference article, (Accessed on Sep 19, 2023) Available from: Radiopaedia.org

17.. Lall NU, Hogan MJ, Caroli disease and the central dot sign: Pediatr Radiol, 2009; 39; 754

18.. Giacobbe C, Di Dato F, Palma D, Rare variants in PKHD1 associated with Caroli syndrome: Two case reports: Mol Genet Genomic Med, 2022; 10(8); e1998

19.. Xu HX, Contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the biliary system: Potential uses and indications: World J Radiol, 2009; 1(1); 37-44

20.. Castro P, Werner H, Matos APP, Peixoto-Filho FM, Caroli’s syndrome evaluated by ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging during pregnancy: Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 2020; 56(1); 125-27

21.. Desmet VJ, Tania S, Peter VE: Oxford Textbook of Clinical Hepatology, 1991; 497-519, Springer

22.. Lendoire J, Barros Schelotto P, Alvarez Rodríguez J, Bile duct cyst type V (Caroli’s disease): Surgical strategy and results: HPB (Oxford), 2007; 9(4); 281-84

23.. Fard-Aghaie MH, Makridis G, Reese T, The rate of cholangiocarcinoma in Caroli disease a German multicenter study: HPB (Oxford), 2022; 24(2); 267-76

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Table showing both the complete blood count (full hemogram) and the liver function test results at the Emergency Department before admission. Values in red are outside the reference range.

Table 1.. Table showing both the complete blood count (full hemogram) and the liver function test results at the Emergency Department before admission. Values in red are outside the reference range. Table 2.. Table showing all complete blood count (full hemogram) results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range.

Table 2.. Table showing all complete blood count (full hemogram) results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range. Table 3.. Table showing all liver function test results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range.

Table 3.. Table showing all liver function test results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range. Table 1.. Table showing both the complete blood count (full hemogram) and the liver function test results at the Emergency Department before admission. Values in red are outside the reference range.

Table 1.. Table showing both the complete blood count (full hemogram) and the liver function test results at the Emergency Department before admission. Values in red are outside the reference range. Table 2.. Table showing all complete blood count (full hemogram) results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range.

Table 2.. Table showing all complete blood count (full hemogram) results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range. Table 3.. Table showing all liver function test results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range.

Table 3.. Table showing all liver function test results during the hospital stay. Values in red are outside the reference range. In Press

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943467

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250