28 November 2023: Articles

Invasive Group G Streptococcal Infection Complicated by Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome: A Case Report

Management of emergency care, Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Hironori Nakamura1ABCDEFG*, Seiji Adachi1BDE, Yukari Uno12BD, Masatoshi Mabuchi1BD, Makoto Shimazaki1D, Shinji Nishiwaki1D, Masahito Shimizu2DDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942206

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e942206

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Group G streptococcus (GGS) infection is reported to have invasive pathogenicity similar to that of group A streptococcus (GAS) infection, causing a strong systemic inflammatory response with bacteremia and various complications. Herein, we report a case of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) as a rare complication of a GGS infection.

CASE REPORT: An 89-year-old Japanese man presented to our hospital with gastrointestinal bleeding and shoulder pain. Close examination revealed a refractory duodenal ulcer (DU) with disseminated intravascular coagulation and soft tissue infection of the right arm, which was found to be caused by GGS. A hemorrhagic tendency due to disseminated intravascular coagulation made it difficult to achieve hemostasis, leading to repeated blood transfusions. Although remission of both the DU and infection was achieved with treatment, impairment of swallowing function and vision subsequently appeared. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed hyperintense lesions with elevated apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). The patient was diagnosed with PRES, which did not improve even after discharge on day 118.

CONCLUSIONS: GGS infection developed with refractory duodenal ulcer bleeding, resulting in PRES with irreversible sequelae. The occurrence of PRES, which may be a rare complication of GGS infection, should be considered when central nervous system manifestations are observed in case of invasive streptococcal infection with a systemic inflammatory response.

Keywords: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, Posterior Leukoencephalopathy Syndrome, Streptococcal Infections

Background

Beta-hemolytic streptococci isolated from humans may possess Lancefield group A, B, C, G, F, or L antigens. Among these isolates, only group A Streptococcus (GAS;

Since approximately 2000, invasive group G streptococcus (GGS) infections, such as those involving SDSE, have frequently been reported worldwide, in addition to infections caused by GAS and GBS [2]. GGS infections are reported to have a similar pathogenicity to GAS infections, and in elderly patients with underlying diseases, accompanying bacteremia results in multiple organ failure [2–4]. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) was first defined in 1993 with the isolation of GAS, with parameters indicative of multiple organ failure. In 2006, the Japanese diagnostic criteria for severe invasive streptococcal infection, equivalent to STSS, were revised to include all streptococci that exhibit beta-hemolysis as causative organisms [5].

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) was first reported in 1996 by Hinchey et al. as reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (RPLS), which includes clinical symptoms of headache, consciousness disturbance, convulsions, and visual abnormalities with edematous changes that mainly occur in the white matter of the parietal and occipital lobes [6]. In 2000, Casey et al. reported that RPLS also has lesions in the gray matter; thus, the disease name PRES was adopted and disseminated [7]. Vascular endothelial damage occurs because of the direct effect of a rapid increase in blood pressure and its fluctuations, and the autoregulatory ability of cerebral blood flow is lost. Impaired autoregulation results in increased perfusion pressure in the more vulnerable microvessels distal to resistant vessels. As a result, the blood-brain barrier is disrupted, and serum leakage into the perivascular space leads to angioedema [8]. In addition to hypertension, the triggers of PRES include eclampsia, immunosuppressants (e.g., cyclosporine), collagen disease, antineoplastic agents, sepsis, and blood transfusion, but approximately 15%–20% of all PRES cases lack an apparent increase in blood pressure [9–11]. Furthermore, Bartynski et al. detected an association with infection/sepsis/shock in 23% of PRES patients [12].

We herein report the case of an elderly man who survived after developing an invasive GGS infection with refractory duodenal ulcer bleeding followed by PRES with apparent neurological sequelae.

Case Report

An 89-year-old Japanese man was transported to the emergency department of our hospital by an ambulance. A large volume of tarry stool was observed, and his systolic blood pressure dropped to approximately 80 mmHg; thus, upper gastrointestinal bleeding was suspected. He had a history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prostate cancer, and regularly visited our hospital as an outpatient. His regular medications included antihypertensive drugs (amlodipine, azilsartan, and bisoprolol fumarate), antiplatelet agent (cilostazol), and oral anti-androgen drugs as hormone therapy for prostate cancer. However, the patient did not undergo any chemotherapy. His medical history included bilateral femoral trochanteric fractures, which had occurred 2 years previously, and aspiration pneumonia, which had occurred 4 years previously. On admission, the patient was 151.2 cm tall and he weighed 40.4 kg. His level of consciousness was clear. Physical examination revealed a body temperature of 36.9°C, blood pressure of 94/58 mmHg, and heart rate of 75 beats/min. His heart and breath sounds were normal. His abdomen was soft and flat, and no edema was observed on his extremities. The right shoulder and upper arm were swollen, and heat and tenderness were present. However, no blisters, necrosis, or redness were observed on the body surface.

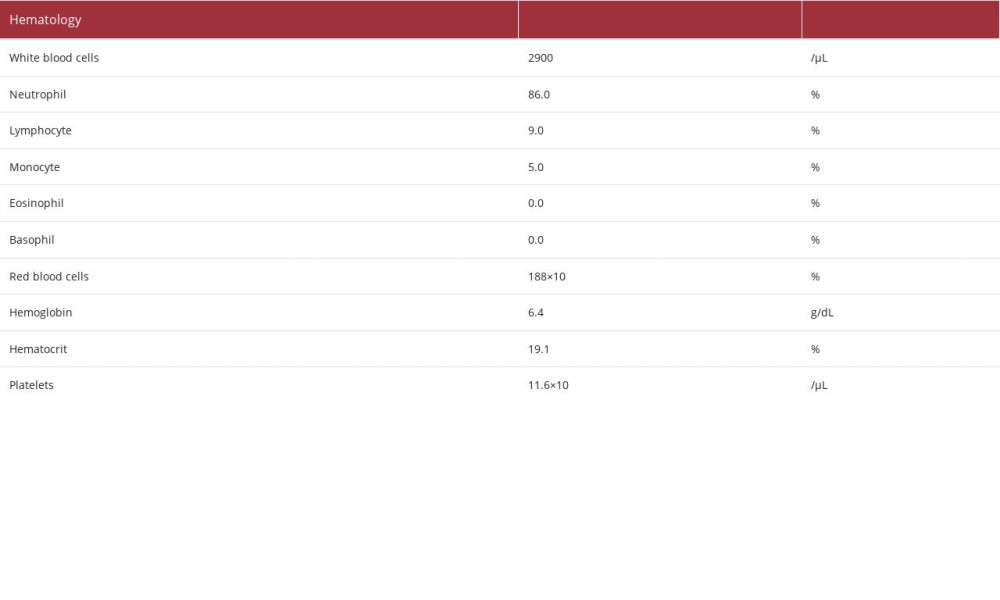

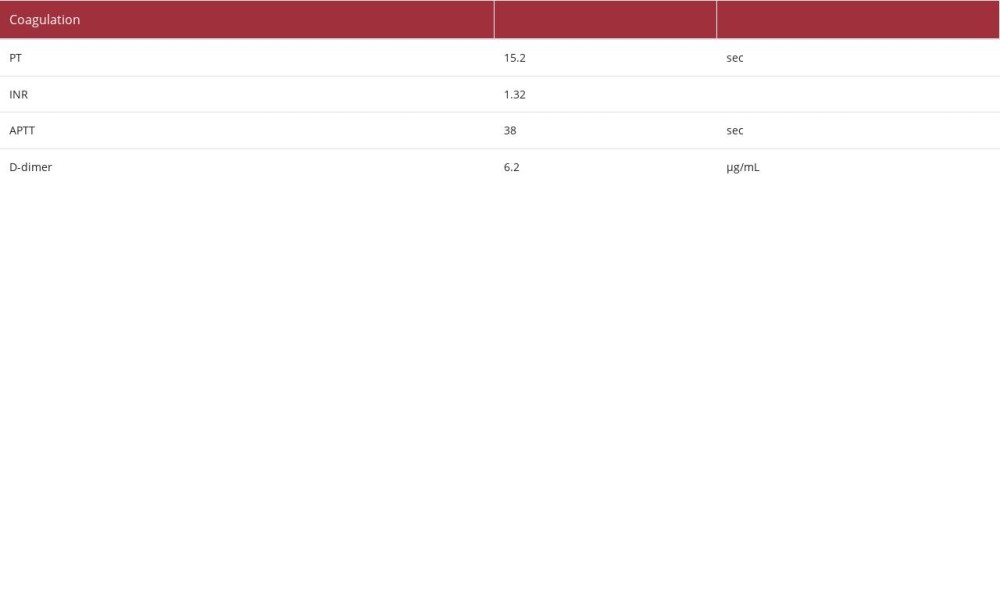

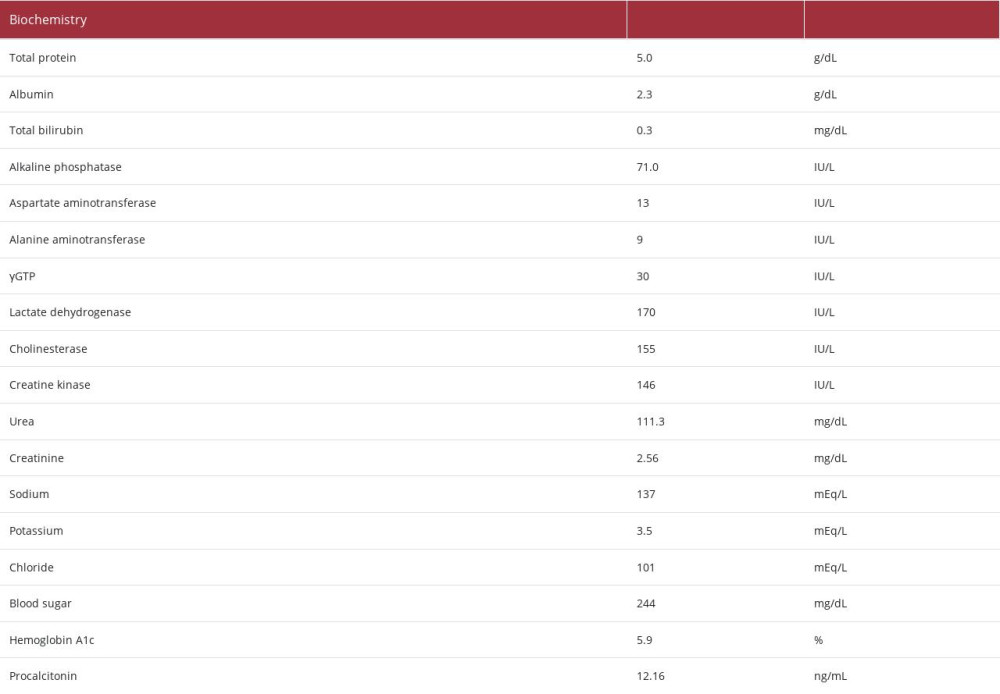

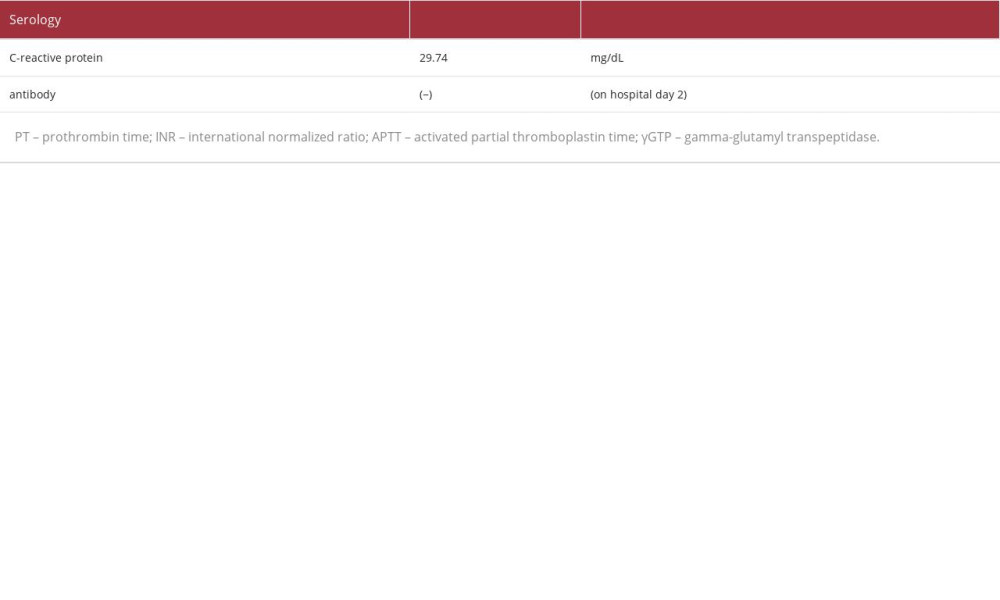

Laboratory analysis revealed the following (Table 1): a decrease in the white blood cell count (2900/μL) and elevated C-reactive protein (29.74 mg/dL) and procalcitonin (12.16 ng/ mL). These findings suggested the presence of severe bacterial infection. The patient’s hemoglobin level was 6.4 g/dL, indicating anemia, with a decreased white blood cell count (2900/μL [as mentioned above]), and decreased platelet count(11.6×104/μL). The patient’s urea nitrogen level had increased to 111.3 mg/dL, and his creatinine level had increased to 2.56 mg/dL. These findings were considered the result of a combination of gastrointestinal bleeding and deterioration of renal function due to dehydration. The lactate dehydrogenase and bili-rubin levels were within the normal range, and the creatinine level was relatively easily improved by fluid replacement. We did not observe hemolytic anemia and progressive renal dys-function, or suspected hemolytic uremic syndrome. A blood test performed the day after hospitalization confirmed that the patient was negative for

Initial endoscopy revealed the presence of multiple ulcers and erosions in the descending duodenum, including some with adherent clots. Endoscopy performed the following day showed gushing bleeding in the inner part of the duodenum (Figure 1A), and hemostasis was achieved using clips and local injection of 2 ml of hypertonic saline epinephrine solution (Figure 1B). However, rebleeding appeared after several days, and laboratory data met the diagnostic criteria for disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Therefore, we decided to switch our approach to hemostasis using interventional radiology.

Celiac angiography revealed extravasation at the periphery of the gastroduodenal artery, and embolization therapy was performed with 4 interlocking detachable coils (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) (Figure 1C). After embolization therapy, hypotension was no longer observed. However, despite these efforts, tarry stool continued, and anemia gradually progressed. Finally, endoscopic hemostasis was achieved using an over-the-scope clip (OTSC; Ovesco, Tübingen, Germany) [13] (Figure 1D, 1E). In a series of events, the patient underwent frequent blood transfusion (26 units of red blood cells, 30 units of platelet concentrate, and 8 units of fresh-frozen plasma) in an effort to manage the refractory duodenal ulcer bleeding. Surgical hemostasis was avoided because of the patient’s aggravated general condition and advanced age.

Computed tomography revealed severe swelling of the subcutaneous tissue with internal gas (Figure 2A–2E) in the right upper arm. In addition, beta-streptococci (group G) were detected in the blood cultures. Therefore, the focus of the infection that triggered DIC was considered to be the skin and soft tissue of the upper right arm. Because the laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC) score [14–16] was 9, necrosis of the lesion was clinically suspected. We continued conservative treatment with a drip infusion of antibacterial agents (ceftriaxone [2 g, daily for 12 days], clindamycin [1200 mg, daily for 14 days], vancomycin [1 g, daily for 12 days], and cefotiam [2 g, daily for 12 days]) without debridement because gastrointestinal bleeding was still poorly controlled and accompanied by DIC (Figure 3). Fortunately, no necrotic tissue or redness was observed, although both heat and swelling were observed on the body surface. The bacteria showed good

Disorientation due to dementia was observed at the start of the hospitalization. Although there was no marked change in his level of consciousness, attention disturbances became evident a few days after admission. Since it soon became difficult for him to take oral medicine, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy was performed on day 25, when the gastrointestinal bleeding had subsided, after which vonoprazan (20 mg/ day) was administered along with the initiation of nutritional management via gastrostomy. However, he continued to have difficulty consuming food orally after the onset.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on day 47, revealing hyperintense lesions with elevated apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values (Figure 4A) on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) (Figure 4B), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (Figure 4C), and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (Figure 4D). The patient was diagnosed with PRES [6,7]. He showed no reaction, even when a hand was waved vigorously in front of his eyes, which can reflect visual impairment as a focal symptom of the lesion. In retrospect, PRES is considered to have developed early after the onset of gastrointestinal bleeding. During hemostasis treatment for gastrointestinal bleeding, his blood pressure fluctuated significantly. A high blood pressure level of up to 186/91 mmHg was temporarily observed due to the discontinuation of antihypertensive drugs on the day after embolization therapy, although no vasopressor was administered. Thereafter, the systolic blood pressure remained at 110–180 mmHg until the oral administration of antihypertensive drugs was resumed via gastrostomy. These symptoms associated with PRES persisted, even after the patient was discharged on day 118.

Discussion

In the present case, the beta-hemolytic streptococci detected in the patient’s blood culture were classified as group G, although we regretfully did not identify the subspecies of bacteria. In general, group G hemolytic streptococcal infections are endemic to the human nasal cavity, skin, genitals, and intestinal tract and can cause skin and soft tissue infections in elderly people with underlying diseases (e.g. malignant tumors, heart disease, and diabetes) [2–4,17]. In comparison to group A hemolytic streptococci, group G hemolytic streptococci have similar virulence-related streptolysin O, streptokinase, and M proteins, and thus exhibit a similar invasive pathological condition; the associated mortality rate has been reported to be 3.3–17.3% [2,3,17]. Currently, streptolysin O exerts hemolytic and cytotoxic effects by damaging the cell membrane, streptokinase has fibrinolytic effects, and the M protein confers resistance to phagocytosis [18–20]. In the present case, shock symptoms, acute kidney injury, refractory duodenal ulcer bleeding, DIC, and soft tissue infection of the right upper arm were observed, suggesting an association with a serious invasive streptococcal infection.

In the present case, it was difficult to control the gastrointestinal bleeding. From a technical perspective, the duodenal ulcer forms in the descending portion of the duodenum, which is the furthest point accessible by the upper gastrointestinal scope. Because the working space was small, it was difficult to maintain the endoscopic field of view and focus on the bleeding point from the front. Another reason for the difficulty in achieving hemostasis in this case is that gastrointestinal bleeding was associated with DIC. DIC that accompanies infection usually exhibits a fibrinolytic-suppressed type, and organ damage is the main symptom, with the mild elevation of FDP and D-dimer levels [21,22]. Since beta-hemolytic streptococci produce streptokinase, dissolve microthrombi, and promote fibrinolysis, which converts plasminogen to plasmin, which in turn degrades fibrin and increases the levels of FDP [23], it is probable that streptokinase is involved in hemorrhagic tissue necrosis. In addition, since abscess formation was observed in the necrotic lesion of the right upper arm, the high FDP and D-dimer levels might have continued for a relatively long time, persisting for approximately one month, even after the platelet level had recovered. Furthermore, venous thrombosis was not observed on venous ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Therefore, we hypothesized that prolonged high levels of FDP and D-dimer, which are fibrinolytic markers, may be related to prolonged hemorrhagic tendency after recovery from consumption coagulopathy, resulting in subcutaneous hematoma.

Our patient was complicated PRES and showed related sequel-ae. PRES is generally known to occur in lesions with high intensity on T2WI/FLAIR imaging, with elevated ADC values appearing on MRI, reflecting the pathophysiology of angioedema in the parietal and occipital lobes [6,7,9–11]. These lesions are usually reversible, which means that the clinical symptoms tend to improve. However, there are some exceptional cases of high-intensity lesions on DWI and low values on ADC maps. Since these diffusion-restricted lesions are usually irreversible, the accompanying clinical symptoms tend to only partially improve [10,11]. Previous reports shown that approximately 10–20% of patients tend to have neurological sequel-ae, even though the name of the disease includes the word “reversible” [10,11]. In this case, MRI showed a high-intensity lesion on DWI, and neurological sequelae, including visual and physical impairment, persisted despite treatment.

Cases of PRES associated with inflammatory diseases are not infrequent, although hypertensive encephalopathy is often cited as the primary etiology of PRES [11,12,24]. In cases in which culture studies were performed, Gram-positive bacteria were reportedly detected in target organs or blood cultures in 84% of PRES cases associated with infection, sepsis, or shock [12]. Increased vascular permeability due to inflammatory cytokines is presumed to be associated with PRES caused by infection, sepsis, or shock. Gram-positive bacteria produce exotoxins, which often act as superantigens to activate more T cells than Gram-negative bacteria, thereby producing large amounts of cytokines [12,25]. The close association of PRES with Gram-positive bacteria may be due to the superantigens produced by these bacteria [12]. There are some rare case reports of acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis complicated by PRES in children [26,27]. Hypertension occurs in most patients with glomerulonephritis, and strict control of hyper-tension is recommended. The onset of PRES is thought to be related to hypertension; however, infection with beta-hemolytic

The rapid increase in blood viscosity and blood pressure associated with blood transfusion is also thought to be related to PRES [28–30]. However, cases of PRES occurring after transfusion are relatively rare [30]. Regarding the mechanism of the increase in blood pressure associated with blood transfusion, the exact mechanism through which PRES occurs after blood transfusion is not fully understood. However, it has been shown that blood viscosity increases exponentially with an increase in the hematocrit, and peripheral vascular resistance leading to hypertension increases because of an increase in blood viscosity [28–30]. These factors are thought to be associated with the development of PRES after blood transfusion. According to Nakamura et al., most cases in which PRES occurred in women and after transfusion were affected by chronic anemia lasting for more than one month [30]. However, the patient in the present case was a man who developed acute anemia due to gastrointestinal bleeding. Furthermore, sepsis in this case developed because of Gram-positive group G hemolytic streptococci. Taken together, these findings suggest that the occur-rence of PRES is more closely related to the effects of infection, sepsis, and shock than to blood transfusion, although the possibility that both factors had an impact on the occurrence of PRES in this case should be considered.

In summary, we encountered a case of an invasive group G hemolytic streptococcal infection with a variety of life-threatening complications, including refractory duodenal ulcer bleeding, DIC, soft tissue infection of the right arm, and PRES. As a point of reflection, we were unable to determine the details of visual impairment at an early stage, as these can only be obtained through interviews with the patient and neurological examinations, thus delaying the discovery of PRES. As a result, we missed the appropriate timing to consider treatment for PRES. In addition, early bleeding control could have eliminated the need for frequent blood transfusions, thus preventing the development of PRES. It is also possible that hemostasis with IVR was unsuccessful because only the artery proximal to the bleeding site was embolized. It is possible that the prognosis of PRES could thus have been improved if antihypertensive treatment had been administered soon after hemostasis was achieved. Regarding neurological complications, our search revealed no previous case reports describing PRES associated with GGS, although there are reported cases of meningitis associated with GBS and critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP) associated with critical conditions, such as sepsis or multi-organ failure [31].

Conclusions

GGS infection develops with refractory duodenal bleeding, resulting in PRES with irreversible sequelae. The occurrence of PRES, which may be a rare complication of GGS infection, should be considered when central nervous system manifestations are observed in patients with invasive GGS infection and a systemic inflammatory response.

Figures

References:

1.. Vandamme P, Pot B, Falsen E: Int J Syst Bacteriol, 1996; 46; 774-81

2.. Takahashi T, Ubukata K, Watanabe H: J Infect Chemother, 2011; 17; 1-10

3.. Takahashi T, Sunaoshi K, Sunakawa K: Clin Microbiol Infect, 2010; 16; 1097-103

4.. Baxter M, Morgan M, Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome caused by group G streptococcus, United Kingdom: Emerg Infect Dis, 2017; 23127-29

5.. , Infectious diseases weekly report (IDWR), Japan Available from: https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/ja/tsls-m/1190-idsc/1815-idwrs201212.html

6.. Hinchey J, Chaveset C, Appignani B, A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome: N Engl J Med, 1996; 334; 494-500

7.. Casey SO, Sampaio RC, Michel E, Truwit CL, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: Utility of fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR imaging in the detection of cortical and subcortical lesions: Am J Neuroradiol, 2014; 21; 1199-206

8.. Bartynski WS, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, Part 2: Controversies surrounding pathophysiology of vasogenic edema: Am J Neuroraddiol, 2008; 29; 1043-49

9.. Racchiusa S, Mormina E, Ax A, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) and infection: A systematic review of the literature: Neurol Sci, 2019; 40; 915-22

10.. Okamoto K, Motohashi K, Fujiwara H, PRES: [Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome]: Brain Nerve, 2017; 69; 129-41 [in Japanese]

11.. Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: Clinical and radiological manifestations, pathophysiology, and outstanding questions: Lancet Neurol, 2015; 14; 914-25

12.. Bartynski WS, Boardman JF, Zeigler ZR, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in infection, sepsis, and shock: Am J Neuroradiol, 2006; 27; 2179-90

13.. Schmidt A, Gölder S, Goetz M, Over-the-scope clips are more effective than standard endoscopic therapy for patients with recurrent bleeding of peptic ulcers: Gastroenterology, 2018; 155; 674-86

14.. Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: A tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections: Crit Care Med, 2004; 32; 1535-41

15.. Martinez M, Peponis T, Hage A, The role of computed tomography in the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections: World J Surg, 2018; 42; 82-87

16.. Stevens DL, Bryant AE, Necrotizing soft-tissue infections: N Engl J Med, 2017; 377; 2253-65

17.. Miyoshi K, Hase R, Shimizu A, [A group G streptococcal bacteremia case series and comparison of community and nosocomial infections.]: Kansenshogaku Zasshi, 2017; 91; 553-57 [in Japanese]

18.. Sogawa K, Kobayashi M, Suzuki J, Inhibitory activity of hydroxytyrosol against Streptolysin O-induced hemolysis: Biocontrol Sci, 2018; 23; 77-80

19.. Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J, Sziegoleit A, Mechanism of membrane damage by streptolysin-O: Infect Immun, 1985; 47; 52-60

20.. Humar D, Datta V, Bast DJ, Streptolysin S and necrotizing infection infections produced by group G streptococcus: Lancet, 2002; 359; 124-29

21.. Asakura H, Classifying types of disseminated intravascular coagulation: Clinical and animal models: J Intensive Care, 2014; 2; 20

22.. Wada H, Matsumoto T, Yamashita Y, Diagnosis and treatment of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) according to DIC guidelines: J Intensive Care, 2014; 2; 15

23.. Kazemi F, Arab SS, Mohajel N, Computational simulations assessment of mutations impact on streptokinase (SK) from a group G streptococci with enhanced activity – insights into the functional roles of structural dynamics flexibility of SK and stabilization of SK-μplasmin catalytic complex: J Biomol Struct Dyn, 2019; 37; 1944-55

24.. Schwartz RB, Jones KM, Kalina P, Hypertensive encephalopathy: Finding on CT, MRI imaging, and SPECT imaging in 14 cases: Am J Roentgenol, 1992; 159; 379-83

25.. Bannan J, Visvanathan K, Zabriskie JB, Structure and function of streptococcal and staphylococcal superantigens in septic shock: Infect Dis Clin North Am, 1999; 13; 387-463

26.. Javaria R, Rushan H, Fauzia Z, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome secondary to acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis in a 12-year-old girl: J Coll Physicians Surg Pak, 2018; 28; 80-81

27.. Park JM, Oh SH, Kim J, Lee JH, Atopic dermatitis with group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus skin infection complicated by posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: Arch Dermatol, 2009; 145; 846-47

28.. Matsushima M, Takahashi I, Houzen H, [A case of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome occurring after anemia correction.]: Rinsho Shinkeigaku, 2012; 52; 147-51 [in Japanese]

29.. Shiraishi W, Blood transfusion-induced posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome presenting severe brain atrophy: A report of two cases: Clin Case Rep, 2022; 10; e05286

30.. Nakamura Y, Sugino M, Tsukahara A, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome with cytotoxic edema after blood transfusion: A case report and literature review: BMC Neurol, 2018; 18; 190

31.. Bolton CF, Gilbert JJ, Hahn AF, Sibbald WJ, Polyneuropathy in critically ill patients: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 1984; 47; 1223-31

Figures

In Press

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943467

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943376

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250