14 March 2024: Articles

Navigating Inconclusive Upper-Gastrointestinal Series in Infantile Bilious Vomiting: A Case Series on Intestinal Malrotation

Unusual clinical course, Challenging differential diagnosis

Yi Xian Low1ABCDEF*, Yi Ming Teo1ABCDEF, Yang Yang Lee2AD, Yoke Lin Nyo2AD, Dale Lincoln Loh2AD, Vidyadhar Padmakar Mali2ADEFDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943056

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943056

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Bilious vomiting in a child potentially portends the dire emergency of intestinal malrotation with volvulus, necessitating prompt surgical management, with differentials including small-bowel atresia, duodenal stenosis, annular pancreas, and intussusception. Although the upper-gastrointestinal series (UGI) is the diagnostic investigation of choice, up to 15% of the studies are inconclusive, thereby posing a diagnostic challenge.

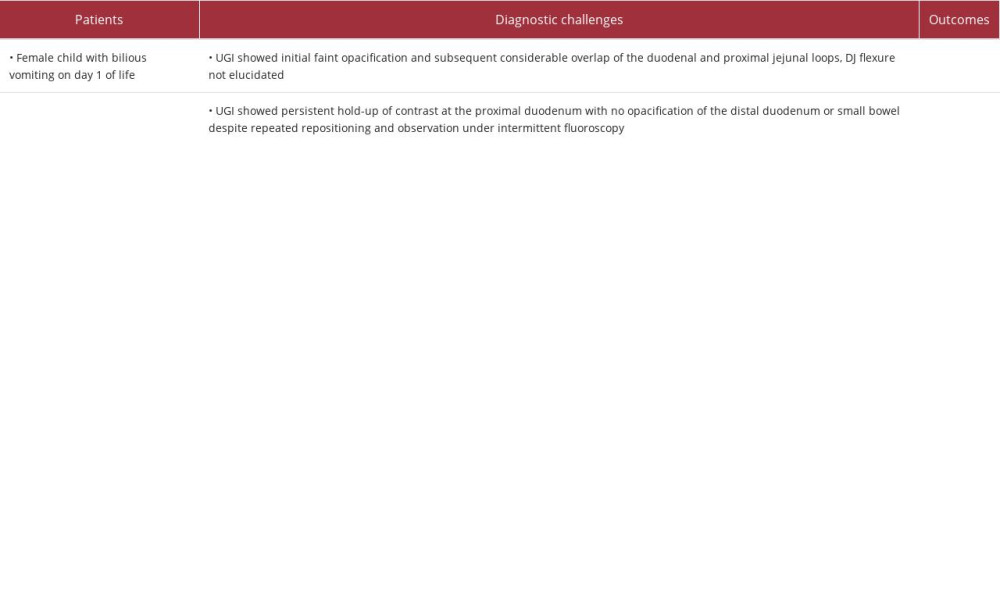

CASE REPORT: We report a case series of 3 children referred for bilious vomiting, whose initial UGI was inconclusive and who were eventually confirmed to have intestinal malrotation at surgery. The first child was a female born at 37 weeks with antenatally diagnosed situs inversus and levocardia, who developed bilious vomiting on day 1 of life. The duodenojejunal flexure (DJ) could not be visualized on the UGI because of faint opacification on first pass of the contrast and subsequent overlap with the proximal jejunal loops. The second child was a male born at 36 weeks, presenting at age 4 months with bilious vomiting of 2 days duration. The third child was a female born at 29 weeks, presenting with bilious aspirates on day 3 of life. UGI for all 3 showed persistent hold-up of contrast at the proximal duodenum with no opacification of the distal duodenum or small bowel. Adjunctive techniques during the UGI and ultrasound examination helped achieve a preoperative diagnosis of malrotation in these children.

CONCLUSIONS: Application of diagnostic adjuncts to an inconclusive initial UGI may help elucidate a preoperative diagnosis of intestinal malrotation in infantile bilious vomiting.

Keywords: Fluoroscopy, Infant, Ultrasonography, Doppler, Volvulus of Midgut, Vomiting

Background

An upper-gastrointestinal series (UGI) is usually the investigation of choice for patients who are clinically suspected to have intestinal malrotation. However, the imaging features in approximately 3–15% of UGI are inconclusive and may result in false-negative or false-positive inferences [1,2]. To increase diagnostic accuracy, techniques for optimal image acquisition and adjunctive imaging modalities may be utilized. We describe 3 cases in our institution in which adjunctive techniques and imaging modalities clarified an initially inconclusive UGI. There is currently no evidence-based decision-making algorithm on how to proceed when faced with an inconclusive UGI in an infant with bilious vomiting. To this end, we propose a diagnostic approach based on these illustrative cases and a literature review on the topic.

Case Reports

PATIENT 1:

This was a female child born at 37 weeks with antenatally diagnosed situs inversus and levocardia, who developed frequent regurgitation and 1 episode of bilious vomiting on day 1 of life. She was otherwise alert and active with a non-dis-tended and soft abdomen. Laboratory markers including blood gas on initial presentation did not show significant derangement. A chest and abdominal radiograph showed gastric bubble in the right hypochondrium (blue circle) in keeping with situs inversus, but no dilated bowel loops (Figure 1). Real-time UGI showed initial faint opacification and subsequent considerable overlap of the duodenal and proximal jejunal loops, with the duodenojejunal (DJ) flexure not elucidated (Figure 2).

The nasogastric tube was advanced into the duodenum and contrast was injected to selectively opacify the duodenum. This selective duodenography revealed the duodenal loop and DJ flexure on the left side of the spine, with the latter below the duodenal bulb level. No definite “corkscrew” appearance of the opacified small bowel loops typical for midgut volvulus was visualized. The opacified small-bowel loops were in the left side of the abdomen (Figure 3). Further images revealed the caecum in the epigastric region and colonic loops on the right side of the abdomen (Figure 4A). Together with a DJ flex-ure left of midline, which was seen on the preceding selective duodenography (Figure 4B), imaging features suggested a narrow mesenteric pedicle with attendant risk of midgut volvulus.

At laparotomy, the DJ flexure was to the left of the midline and partly abdominal in location. This abdominal duodenum had developed 2 hairpin turns with associated adhesions seen over the second and third parts of the duodenum, which were located to the left of the midline. The caecum was free-floating in the midline epigastrium with a narrow small-bowel mesenteric pedicle. The superior mesenteric vein (SMV) was on the right side of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) (Figure 4C), representing reversal of SMV/SMA. There was no volvulus or bowel ischemia. A Ladd procedure was performed, with an uneventful post-operative recovery.

PATIENTS 2 AND 3:

These were a male child born at 36 weeks, presenting at 4 months of age with bilious vomiting for 2 days duration, and a female child born at 29 weeks who presented with bilious aspirates on day 3 of life. The male child had no bowel output for 1 day duration, had high bilirubin levels, and dehydration with 11% weight loss. The patient’s blood gases did not show significant derangement. The female child was progressively unable to tolerate feeds with increasing bilious aspirates, and blood gases showed mild metabolic alkalosis.

Abdominal radiographs for both these patients similarly showed gas-distended stomachs with relative paucity of gas-distended bowel loops elsewhere in the abdomen. UGI initially showed contrast flowing smoothly from the stomach into the proximal duodenum. Thereafter however, there was persistent hold-up of contrast at the proximal duodenum with no opacification of the distal duodenum or small bowel despite repeated repositioning and observation under intermittent fluoroscopy. An immediate ultrasound (US) showed an inverse SMA/SMV relationship, along with whirlpool sign of swirling of the mesenteric vessels (Figures 5, 6).

Intra-operatively, the male child was found to have intestinal malrotation with Ladd’s band in the right lateral aspect, high-riding cecum next to the duodenum in the right hypochondrium, and narrowed root of mesentery. The female child had intestinal malrotation with caecum in the left hypochondrium and small bowel displaced to the right abdomen posterior to the caecum. The entire duodenum was on the right, with dense and broad Ladd’s bands across the first and second part of the duodenum likely accounting for the obstruction. Both children had Ladd procedures and appendicectomies with uneventful post-operative recovery.

The pertinent features of the cases presented are summarized in Table 1.

Discussion

SELECTIVE DUODENOGRAPHY:

The NGT can be purposefully advanced to lie in the proximal duodenum, allowing for performance of a “selective duodenogram” [5]. This allows the timing, pressure, and volume of the contrast medium bolus to be controlled, thereby expediting the procedure, possibly reducing radiation exposure, and resulting in distension of the duodenum during a contrast bolus. In the first child, selective duodenography allowed the visualization of the DJ flexure and guided the distal passage of contrast thereafter. The technique involved pushing the in-dwelling NGT beyond the pylorus, and administering 2–3 ml of contrast bolus. A retrospective study by Andronikou et al in 101 patients showed that the selective duodenogram technique demonstrated the duodenum with 100% success, with significantly more frequent first-pass bolus visualization and duodenal distention than traditional studies [5].

MANUAL EPIGASTRIC COMPRESSION:

In malrotation, the position of the DJ junction may not always be grossly abnormal, such that UGI can mimic a normal appearance [6]. When there is uncertainty, epigastric compression can be used to assess the DJ junction mobility. Usually, children aged less than 4 years old have lax bowel ligaments, which enables greater mobility of the DJ junction. In contrast, children with malrotation do not have mobile DJ junctions [2].

Manual epigastric compression involves applying a compression pressure no more than that applied for abdominal palpation during physical examination. In normal infants with a mobile duodenum, the DJ junction should return to a normal position after compression is released. In contrast, in patients with malrotation, the DJ junction remains in an abnormal position even after release of compression [6].

ULTRASOUND (US):

US has emerged as a complementary imaging modality to assess for malrotation. The intestinal whirlpool sign, along with the reversed SMA and SMV positions, have been shown to be highly accurate imaging findings for malrotation and volvulus [7]. As illustrated in our second and third patients, the inverse SMA/SMV relationship on US prompted urgent surgical intervention for intestinal malrotation. A retrospective study by Binu et al recommends the use of water as a contrast medium under US guidance [3]. A fluid bolus is instilled via an indwelling NGT. After the pylorus is located, the passage of the fluid bolus is traced into the first part of the duodenum (D1). The transducer is then moved downwards to locate D2 as the fluid bolus progresses through the duodenum. Normally, the third part of the duodenum (D3) would course medially while traversing between the superior mesenteric vessels and the aorta. As the bolus is followed into D3, malrotation can be excluded by visualizing the normal retroperitoneal transverse course of D3. This would represent normal embryological development, in contrast to an intraperitoneal D3, which would be suspicious for malrotation. Finally, the transducer is moved upwards towards the SMA origin to follow the bolus into the fourth part of the duodenum (D4). Visualizing D4 with superior extent up to that of the SMA origin would demonstrate that the DJ flexure is in a normal position. In their study of 539 patients, all the patients who had US findings of malrotation had confirmatory intra-operative findings.

An expert panel narrative review by Nyugen et al recommends for a choice to be made between upper-GI contrast study and US depending on the local expertise and available resources [8]. The use of US for the evaluation of midgut rotation and volvulus was found to have comparable performance to that of UGI in terms of sensitivity and specificity, with additional benefits of being radiation-free, less costly, and possibility of being performed at bedside given its portability. They recommend a standardized algorithm when there are available local expertise and resources to perform emergent US. This involves performing US as the first-line investigation. If the US examination is positive for volvulus, then the patient proceeds to surgical evaluation without the need of a confirmatory UGI, which can incur potential treatment delay. If the US is negative for volvulus and malrotation, and does not provide an alternative diagnosis, then the decision between expectant medical management versus further imaging would depend on the patient’s presentation. If US is inconclusive or nondiagnostic, then an emergent UGI is performed.

A prospective study by Zhang et al showed that US could detect malrotation with higher accuracy that UGI, with the whirlpool sign indicating volvulus with a high accuracy of 92.3%. Furthermore, US is helpful in the assessing for the differential diagnoses of bilious vomiting, including annular pancreas and duodenal atresia [9]. Nonetheless, UGI, being the traditional preferred examination for the diagnosis of malrotation, remains a useful tool, and may still be considered first-line, particularly in centers where pediatric US may not be available [10].

In our institution, local experience is as yet unprepared for US to replace UGI as the first-line investigation for infantile bilious vomiting, or even fulfill the role of concurrent first-line investigation together with UGI, as routine practice. However, with the literature showing the merits of US, we anticipate US featuring even more prominently in our diagnostic algorithm of malrotation in the future, with further dedicated training and experience.

DELAYED RADIOGRAPH OR CONTRAST ENEMA:

In equivocal cases of suspected malrotation without clinical features of volvulus, further follow-through images may be helpful to delineate cecal position. Although normal cecal position may be observed in children with malrotation, an abnormal cecal position is seen in up to 80% of children with malrotation [2]. A contrast enema study may also be performed to expedite the identification of the position of the caecum and thus assess the length of mesenteric fixation [8].

CT/MRI:

Malrotation can also be assessed on CT and MRI by the location of the small and large bowel, location of cecum, the presence or the absence of retroperitoneal duodenum, and the SMA-SMV relationship. CT and MRI studies can also help differentiate between malrotation and non-rotation. In non-rotation, the entire small bowel is located in the right abdomen and the colon is located in the left abdomen. CT and MRI have limited utility due to radiation and streak artefact from pre-existing GI contrast, and long duration of image acquisition, respectively [11]. Currently, CT and MRI are not considered in the routine evaluation of malrotation. They may however be useful in centers where pediatric UGI or US expertise is not available, especially given that a time-sensitive diagnosis is required in the setting of intestinal malrotation. CT and MRI can also be helpful for complex cases suspected to have alternative diagnoses [11,12].

In our institution, UGI remains the initial investigation of choice in the workup of children with bilious vomiting and clinical concerns for malrotation. The clinicians are in attendance for real-time feedback and decision-making during the UGI. Real-time visualization reveals gastric emptying/transit time and bowel peristalsis, together with potential point(s) of obstruction.

PROPOSED DECISION-MAKING APPROACH:

We share 2 possible scenarios resulting in inconclusive UGI (Figure 7). In the first scenario with contrast hold-up up to the level of the proximal duodenum, we opine that persisting with further fluoroscopic techniques is of limited value with unwar-ranted radiation penalty to the patient, so we recommend early US evaluation in this scenario. We do not advocate use of selective duodenography in this instance, in view of potential safety concerns of advancing the NGT without knowledge of the cause of the contrast hold-up in the proximal duodenum. The non-opacification of the DJ flexure in this situation would also preclude the usefulness of manual epigastric compression. In the second scenario with contrast past the proximal duodenum but with equivocal DJ flexure position, manual epigastric compression and selective duodenography or US may clarify the diagnosis.

The cecum can be visualized either by performing additional follow-through radiographs during the UGI or an immediate contrast enema to rule out malrotation in an otherwise stable child [13].

Cross-sectional imaging modalities such as CT or MRI are not in routine use in the acute setting of suspected malrotation and volvulus in our institution.

Conclusions

Adjunct measures during the initial upper-gastrointestinal series or an expedited, targeted ultrasound in addition to UGI may clarify the preoperative diagnosis of intestinal malrotation in an infant who presents with bilious vomiting. The proposed decision-making approach arises from our institution’s experience and literature review, and therein lies the limitation of this study. Large-scale multicenter studies may reveal the efficacy of an integrated approach that routinely incorporates these adjuncts into the diagnostic algorithm of malrotation.

Figures

References:

1.. Zhou L, Li S, Wang W, Usefulness of sonography in evaluating children suspected of malrotation: J Ultrasound Med, 2015; 34(10); 1825-32

2.. Applegate KE, Anderson JM, Klatte EC, Intestinal malrotation in children: A problem-solving approach to the upper gastrointestinal series: Radiographics, 2006; 26(5); 1485-500

3.. Binu V, Nicholson C, Cundy T, Ultrasound imaging as the first line of investigation to diagnose intestinal malrotation in children: Safety and efficacy: J Pediatr Surg, 2021; 56(12); 2224-28

4.. Dilley AV, Pereira J, Shi EC, The radiologist says malrotation: Does the surgeon operate?: Pediatr Surg Int, 2000; 16(1–2); 45-49

5.. Andronikou S, Arthur S, Simpson E, Chopra M, Selective duodenography for controlled first-pass bolus distention of the duodenum in neonates and young children with bile-stained vomiting: Clin Radiol, 2018; 73(5); 506.e1-e8

6.. Lim-Dunham JE, Ben-Ami T, Yousefzadeh DK, Manual epigastric compression during upper gastrointestinal examination of neonates: Value in diagnosis of intestinal malrotation and volvulus: Am J Roentgenol, 1999; 173(4); 979-83

7.. Alehossein M, Abdi S, Pourgholami M, Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound in determining the cause of bilious vomiting in neonates: Iran J Radiol, 2012; 9(4); 190-94

8.. Nguyen HN, Navarro OM, Bloom DA, Ultrasound for midgut malrotation and midgut volvulus: AJR expert panel narrative review: Am J Roentgenol, 2022; 218(6); 931-39

9.. Zhang W, Sun H, Luo F, The efficiency of sonography in diagnosing volvulus in neonates with suspected intestinal malrotation: Medicine (Baltimore), 2017; 96(42); e8287

10.. Strouse PJ, Ultrasound for malrotation and volvulus: Has the time come?: Pediatr Radiol, 2021; 51(4); 503-5

11.. Marine MB, Karmazyn B, Imaging of malrotation in the neonate: Semin Ultrasound CT MR, 2014; 35(6); 555-70

12.. Stanescu AL, Liszewski MC, Lee EY, Phillips GS, Neonatal gastrointestinal emergencies: Step-by-step approach: Radiol Clin North Am, 2017; 55(4); 717-39

13.. Kang C, Yoon H, Shin HJ, Bedside upper gastrointestinal series in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: BMC Pediatr, 2021; 21(1); 91

Figures

In Press

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943467

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250