06 March 2024: Articles

Enhanced Diagnostic Capabilities: Ultrasound Imaging of Fetal Alimentary Tract Obstruction with Advanced Imaging Technologies

Challenging differential diagnosis, Diagnostic / therapeutic accidents, Management of emergency care, Unexpected drug reaction, Congenital defects / diseases, Educational Purpose (only if useful for a systematic review or synthesis)

Daniel WolderDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943419

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943419

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Congenital malformations of the alimentary tract constitute 5% to 6% of newborn anomalies, with congenital intestinal atresia being a common cause of alimentary tract obstruction. This study explores advanced ultrasound diagnostic possibilities, including 2D, HDlive, HDlive inversion, and HDlive silhouette imaging modes, through the analysis of 3 cases involving duodenal and intestinal obstructions. Congenital malformations of the alimentary tract often present challenges in prenatal diagnosis. The most prevalent defect is congenital intestinal atresia leading to alimentary tract obstruction, with an incidence of approximately 6 in 10 000 births. We focused on advanced ultrasound diagnostic techniques and their applications in 3 cases of duodenal and intestinal obstructions.

CASE REPORT: Three cases were examined using advanced ultrasound imaging modes. The first patient, diagnosed at week 35 of gestation, revealed stomach and duodenal dilatation. The second, identified at week 32, had the characteristic “double bubble” symptom. The third, at week 31, also had double bubble symptom and underwent repeated amnioreduction procedures. HDlive, HDlive inversion, and HDlive silhouette modes provided intricate visualizations of the affected organs. Prenatal diagnosis of alimentary tract obstruction relies on ultrasound examinations, with nearly 50% of cases being diagnosed before birth.

CONCLUSIONS: Advanced ultrasound imaging modes, particularly HDlive silhouette, play a crucial role in diagnosing fetal alimentary tract obstruction. These modes offer detailed visualizations and dynamic evaluations, providing essential insights for therapeutic decisions. The study emphasizes the importance of sustained fetal surveillance, a multidisciplinary approach, and delivery in a level III referral center to ensure specialized care for optimal outcomes.

Keywords: Prenatal Care, Prenatal Diagnosis, Silhouette sign

Background

Congenital malformations of the alimentary tract account for 5% to 6% of all malformations found in newborns [1]. One of the most common defects during the fetal period is congenital intestinal atresia, which leads to alimentary tract obstruction [2]. The incidence of intestinal obstruction in neonates is approximately 6 in 10 000 births [3]. About half of the cases are diagnosed prenatally [1]. Nearly 50% of all children with congenital alimentary tract obstruction are born prematurely [1]. In neonates with undiagnosed alimentary tract obstruction before birth, clinical manifestations appear in the first few days of life [1]. Congenital duodenal atresia accounts for approximately 60% of all alimentary tract obstruction, being one of the most common forms of these disorders [3]. Obstruction of the jejunum and ileum is less common, and the least common is obstruction of the large intestine [3]. According to data, about 10% of fetuses with duodenal atresia have incomplete intestine rotation (malrotation) or VACTERL association (vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiac abnormalities, tracheoesophageal fistula, esophageal atresia, renal abnormalities or radial dysplasia, and limb abnormalities), and 7% of them have another form of alimentary tract obstruction [3,4]. Congenital duodenal atresia is a group of congenital anomalies involving partial or complete narrowing of the duodenal lumen [3,5]. The etiology can be divided into intrinsic causes: excessive proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells and impaired recanalization of the intestinal lumen in fetal life between weeks 8 and 10 of pregnancy, resulting in duodenal stenosis or atresia; and extrinsic causes leading to duodenal compression: annular pancreas, abnormal intestinal rotation, presence of connective tissue bands that press on the duodenum (Ladd bands), and portal vein lesions [1,5]. As indicated, the most common obstruction of this part of the alimentary tract involves the proximal segment of the jejunum (31%) and the distal segment of the ileum (36%) [6]. As in the case of small intestinal obstruction, the main cause of this pathology is ischemic changes in the intestines in utero, with a greater frequency in male than in female fetuses (4: 3) [3,7]. It can be an isolated defect but also often accompanies other gastrointestinal pathologies, such as Hirschsprung disease and gastroschisis [3]. In the prenatal period, it is based on ultrasound examination. Alimentary tract obstruction leads to impaired passage and absorption of the amniotic fluid swallowed by the fetus, and consequently, very often it is the cause of the development of polyhydramnios [6,8]. However, in case of colonic obstruction, polyhydramnios does not occur, owing to absorption of amniotic fluid within the small intestine [7]. Apart from polyhydramnios, the other canonical symptom of duodenal obstruction is the presence of the “double bubble” symptom in the cross-section of the abdominal cavity, which signifies existence of 2 adjacent fluid-filled echolucent structures, where one of them is a bloated stomach and the other is the initial duodenal segment in front of the stenosis [6,8]. This abnormality can be detected during fetal ultrasonography. A predominantly incorrect image appears around week 20 of gestation. However, when there is only stenosis, this phenomenon occurs later, around week 25 to 30 of gestation. An ultrasono-graphic image includes dilatation of the intestinal loops (greater than 7 mm) and vigorous peristalsis [6,9,10]. The intestinal wall shows increased echogenicity, and in cases of major obstruction, a bloated stomach and duodenum are also visible. The defect is removed during a surgical treatment, which allows restoration of the intestinal integrity and the commencement of oral feeding [11,12]. The initial stage of the procedure is to prepare the newborn for surgery, namely correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalance, cardiopulmonary stabilization, and ensuring thermal comfort. The surgery can be performed using the laparoscopic or conventional method. In both cases, the patency of the gastrointestinal tract is restored, most commonly with side-to-side duodeno-duodenal anastomosis, called diamond-shaped anastomosis [11,12]. During the procedure, the distended upper section of the intestine is incised transversely, and the narrow lower section along the length, just behind the present obstacle, joining both sections end to end. An intestinal probe is passed through the anastomosis for enteral nutrition during recovery from surgery [2–6]. Oral nutrition is usually introduced after a few or more than 12 days, after restoring normal gastrointestinal peristalsis [11–15]. In the Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic of the Regional Hospital in Kielce, 3 cases of fetal alimentary tract obstruction were reported from 2015 to 2017 (1 case of intestinal obstruction and 2 cases of duodenal obstruction). The high-resolution 3D imaging modes HDlive, HDlive inversion, and HDlive silhouette were used to make the diagnosis. The silhouette mode, also known as HDlive silhouette-rendering mode, is a novel technology used in prenatal imaging that provides a vitreous-like clarity of anatomical structures. It allows for the visualization of inner structures with a hologram-like quality, enabling the assessment of spatial relationships among organs and the delineation of their outer contours. This mode has been particularly useful in the prenatal diagnosis of congenital duodenal stenosis, allowing for clearer visualization of anatomical abnormalities and aiding in the evaluation of the site of obstruction and exclusion of other differential diagnoses and complications. It has played a crucial role in the diagnosis and surgical planning of intestinal obstructive pathologies [16].

Case Reports

CASE 1:

In 2015, a multiparous woman with gravida 2 and parity 2 was admitted to the Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic in week 35 of gestation with suspected alimentary tract obstruction in the fetus. Two-dimensional (2D) ultrasound examination showed dilatation of the stomach, duodenum, and intestines (Figure 1) and secondary polyhydramnios, with an amniotic fluid index (AFI) of 28 cm. The application of HDlive silhouette mode enabled more accurate imaging of the changes found in 2D mode. A dilated stomach and duodenum were visualized, and it was possible to see the duodenal lumen (Figure 2). Due to the obstetric history, including a previous cesarean delivery and lack of consent for vaginal delivery, the pregnancy was terminated by cesarean delivery. A male fetus was born in good condition, with an Apgar score of 10 and pH level from cord blood of 7.32. The fetal weight was 2370 g. The newborn was transferred to the Pediatric Surgery Clinic of the Regional Hospital for further diagnostics and treatment.

CASE 2:

In 2016, a patient with gravida 1 and parity 1 was admitted to the clinic in week 32 of gestation. Ultrasound examination revealed the double bubble sign (Figure 3) and secondary polyhydramnios, with an AFI of 25 cm. HDlive (Figure 4) and HDlive inversion (Figure 5) imaging modes were also used during the ultrasound examination, which allowed accurate imaging of the stomach, pylorus, and duodenum, transitioning into the hypo-plastic bowel. On examination, active duodenal peristalsis was found, as evidenced by the change in duodenal shape and the absence of stomach peristalsis. In the HDlive silhouette examination (Figures 6, 7), an image of a bloated stomach and duodenum were obtained, and their lumen could be evaluated. The patient was hospitalized once more at week 34 of gestation. Ultrasonography confirmed duodenal obstruction and polyhydramnios (AFI 27 cm). During stay at the clinic, the patient had abnormal blood pressure values and increasing proteinuria values. Antihypertensive therapy was initiated. The patient delivered by cesarean delivery at week 36 of pregnancy due to increasing symptoms of threatening eclampsia (arterial blood pressure of 160/110 mmHg, daily urine protein levels of 0.74 g/L). A male fetus was born in good condition, with a Apgar scores of 9, 9, 9, and 9 points and pH level from cord blood of 7.36. The fetal weight was 2410 g. The newborn was transferred to the Pathology and Intensive Care Department of the Regional Hospital in Kielce for further diagnostic testing and treatment.

CASE 3:

In 2017, a patient with gravida 2 and parity 2 at week 31 of gestation was admitted to the Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic. Ultrasound examination revealed the double bubble sign (Figure 8) and secondary polyhydramnios, with an AFI of 34 cm. Due to the increasing volume of amniotic fluid, the patient was qualified for an amnioreduction procedure. Due to the repeated increase of amniotic fluid volume to AFI >30 cm, the procedure was repeated 3 times during further hospitalization. The amnioreduction procedures were performed in 2-week intervals and proceeded without complications. The patient was re-admitted to the clinic at week 36 of gestation. Premature out-flow of amniotic fluid was revealed. Ultrasonography confirmed the double bubble sign and polyhydramnios. According to the obstetric history, including a previous cesarean delivery, and lack of consent to attempting vaginal delivery, the patient delivered by cesarean delivery. A female fetus was born in good condition, with an Apgar scores of 9 and 10 points and pH level from cord blood of 7.33. The fetal weight was 2090 g. The newborn was transferred to the Pediatric Surgery Clinic of the Regional Hospital for further diagnostic testing and treatment.

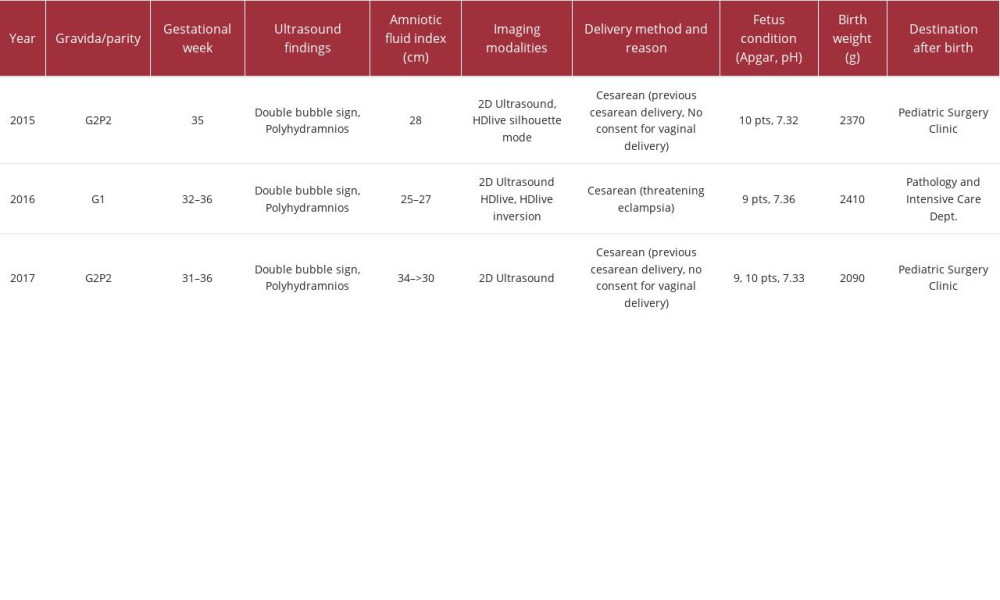

A comparison of these 3 clinical cases collates and contrasts shared characteristics of 3 clinical scenarios, focusing on patient demographics, diagnostic findings, interventions, and outcomes related to fetal duodenal obstruction (Table 1). In all 3 cases, the 3D ultrasound HDlive silhouette technique offered a significant advantage over the traditional 2D method. This is due to the ability to analyze images without the need for the patient’s presence, as the 3D block can be stored and reviewed at any time. This allows for a more comprehensive and detailed assessment of the anatomical structures, aiding in the diagnosis and surgical planning of intestinal obstructive pathologies. Additionally, the HDlive silhouette mode provides a clearer visualization of anatomical structures, allowing for better spatial understanding and improved delineation of outer contours, which is particularly beneficial in diagnosing proximal jejunal atresia. Therefore, the 3D ultra-sound HDlive silhouette mode offers enhanced diagnostic capabilities and spatial visualization, compared with the traditional 2D technique.

Discussion

Alimentary tract obstruction is associated with serious health consequences for the newborn. The disorder could be diagnosed during the prenatal period in about half of cases [11]. The most common causes of obstruction include duodenal atresia, followed by obstruction of the jejunum and ileum [4]. The basis of diagnosis is 2D ultrasound, where the double bubble image and polyhydramnios are usually found [10,11]. Modern ultrasound machines and the use of the new imaging modes HDlive, HDlive inversion, and HDlive silhouette extend the diagnostics and obtain images for a more precise and accurate assessment of the alimentary tract structure, including assessment of peristalsis and the lumen of the viewed organs, which can be helpful in making further therapeutic decisions. If alimentary tract obstruction is suspected, continuous fetal surveillance through repeated ultrasound examinations is necessary, along with assessment of amniotic fluid volume.

Modern ultrasound machines allow the use of the new high-resolution 3D imaging modes HDlive, HDlive inversion, and HDlive silhouette, to isolate the details of individual organs. Using these imaging modes in the diagnosis of the fetal alimentary tract, it is possible to obtain a spatial image of the viewed organ as well as an assessment of its continuity and site of stenosis [2]. It is also possible to obtain an image of the interior from the lumen site of the organs and evaluate their peristalsis [2]. In the case of duodenal atresia, HDlive and HDlive inversion mode enable visualization of the stomach, pylorus, and duodenum [2]. The stomach is bloated without apparent peristalsis. Active peristalsis of the duodenum is apparent, as evidenced by a change in its shape during examination [2]. The HDlive silhouette mode introduced in 2014 allows imaging of the viewed organs as structures, with high transparency [2,6]. By applying a shadowing effect, the outlines of the structure and its interior can be visible at the same time [6]. Moreover, the organs behind the currently viewed ones are visible, which facilitates differentiation with pathologies involving other systems [6]. Duodenal obstruction is one of the most common causes of intestinal obstruction in the prenatal and neonatal period [10]. The disorder can appear as an isolated symptom; however, in many cases, it is an accompanying symptom in malformation syndromes. Duodenal obstruction can be diagnosed during the prenatal period. Prenatal suspicion of the defect is in most cases confirmed after delivery and allows correct diagnosis to be made. The diagnosis of the upper gastrointestinal tract obstruction can be made even before the newborn develops symptoms. For this purpose, an ultrasound examination and an X-ray of the chest and abdomen are performed [11–14]. Presence of a double fluid level in the epigastrium, the so-called double bubble sign, confirms the existence of the defect. After additional medical examination, including heart echocardiography, the double bubble sign is an indication for a surgical procedure [10,13]. In the case of the presence of any accompanying defects, the first and necessary step is to determine the sequence of surgical procedures in order to optimize the individual treatment process. Difficulty in diagnosing duodenal obstruction can appear due to the lack of prenatal diagnosis of the defect. This is often associated with the initiation of oral feeding of the newborn, leading to further complications. Diagnosis delay can also be related to the presence of an incomplete obstruction in the duodenum, which appears in the case of a duodenal septum, annular pancreas, or Ladd bands. In some cases, the diagnosis is made after passage of the upper gastrointestinal tract [11–15]. The HDlive silhouette-rendering mode, in conjunction with magnetic resonance imaging, offers significant advantages over conventional 2D ultrasound in the prenatal evaluation of congenital duodenal stenosis. This advanced technology provides a vitreous-like clarity of anatomical structures, allowing for the visualization of inner structures with a hologram-like quality. It enables the assessment of spatial relationships among organs and the delineation of their outer contours, thereby facilitating the diagnosis of proximal jejunal atresia and aiding in the evaluation of the site of obstruction and the exclusion of other differential diagnoses and complications. Additionally, the 3D reconstruction provided by the HDlive silhouette-rendering mode offers a clearer visualization of the anatomical spatial relationships of the malformation, making it easier to understand the complex anatomy of fetal intestinal obstructions, compared with 2D imaging. Furthermore, the HDlive silhouette-rendering mode has been instrumental in identifying the distal bowel position and evaluating malrotation pathologies, such as midgut volvulus and Ladd bands, through the use of fetal magnetic resonance imaging. These combined techniques play a crucial role in the accurate diagnosis and surgical planning of intestinal obstructive pathologies, ultimately leading to improved prenatal and postnatal outcomes for affected neonates [16–22].

Amnioreduction can be necessary in cases of polyhydramnios. A multidisciplinary prenatal conference, including a perinatologist, neonatologist, and pediatric surgeon, is also necessary to plan further proceedings. The delivery should take place in a level III referral center, where the baby can receive highly specialized care.

Conclusions

HDlive, HDlive inversion, and HDlive silhouette are useful diagnostic methods in the diagnosis of fetal alimentary tract obstruction. HDlive silhouette ultrasound imaging mode allows for accurate identification of the site of intestinal stenosis in fetuses with alimentary tract obstruction. HDlive and HDlive inversion imaging modes allow for dynamic evaluation of the intestines in fetuses with alimentary tract obstruction.

Figures

References:

1.. Błaszczyk M, Kozłowska K, Sosnowska P, [ Congenital duodenal stenosis caused by the presence of Ladd bands, complicated by intestinal adhesions and necrotizing enteritis.]: Pediatrics After Graduation, 2016; 20(3); 22148 Available from: [in Polish]https://podyplomie.pl/pediatria/22148,wrodzone-zarosniecie-dwunastnicy-spowodowane-obecnoscia-pasm-ladda-powiklane-zrostami-jelitowymi

2.. John R, D’Antonio F, Khalil A, Diagnostic accuracy of prenatal ultrasound in Identifying jejunal and ileal atresia: Fetal Diagn Ther, 2015; 38; 142-46

3.. Adams SD, Stanton MP, Malrotation and intestinal atresias: Early Hum Dev, 2014; 90(12); 921-25

4.. Choudhry MS, Rahman N, Boyd P, Lakhoo K, Duodenal atresia: Associated anomalies, prenatal diagnosis and outcome: Pediatr Surg Int, 2009; 25(8); 727-30

5.. Kurjak A, Chervenak FA: Donald School Textbook of Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2017; 88-89, New Delhi, Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Ltd

6.. Pietryga M, [Doppler studies and ultrasonographic prenatal diagnosis.]: Murowana Goślina: Exemplum Publishing House, 2017 [in Polish]

7.. AboEllail MAM, Kanenishi K, Marumo G, Fetal HDlive Silhouette mode in clinical practice: Donald Sch J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 2015; 9(4); 413-19

8.. Norton ME, Scoutt LM, Feldstein VA: Callen’s Ultrasonography in obstetrics and gynecology, 2017; 465-70, Philadelphia, PA, Elsevier

9.. Shironomae T, Satomi M, Kuwahara T, Congenital duodenal and multiple jejunal atresia with malrotation in a patient with Down syndrome: Congenit Anom (Kyoto), 2018; 58(2); 71-72

10.. Korecka K, Respondek-Liberska M, Duodenal obstruction in prenatal ultra-sound examination – duodenal atresia versus annular pancreas – report on two cases and literature review: Prenat Cardio, 2014; 4(2); 29-33

11.. Latzman JM, Levin TL, Nafday SM, Duodenal atresia: not always a double bubble: Pediatr Radiol Aug, 2014; 44(8); 1031-34

12.. Miscia ME, Lauriti G, Lelli Chiesa P, Zani A, Duodenal atresia and associated intestinal atresia: A cohort study and review of the literature: Pediatr Surg Int, 2019; 35(1); 151-57

13.. Saša RV, Ranko L, Snezana C, Duodenal atresia with apple-peel configuration of the ileum and absent superior mesenteric artery: BMC Pediatr, 2016; 16(1); 150

14.. Shironomae T, Satomi M, Kuwahara T, Congenital duodenal and multiple jejunal atresia with malrotation in a patient with Down syndrome: Congenit Anom (Kyoto), 2018; 58(2); 71-72

15.. Botham RA, Franco M, Reeder AL, Formation of duodenal atresias in fibroblast growth factor receptor 2IIIb-/- mouse embryos occurs in the absence of an endodermal plug: J Pediatr Surg, 2012; 47(7); 1369-79

16.. Castro PT, Matos APP, Werner H, Araujo Júnior E, Congenital duodenal stenosis: Prenatal evaluation by three-dimensional ultrasound HDlive Silhouette mode, magnetic resonance imaging, and postnatal outcomes: J Med Ultrasound, 2019; 27(3); 151-53

17.. Jeong SH, Lee MY, Kang OJ, Perinatal outcome of fetuses with congenital high airway obstruction syndrome: A single-center experience: Obstet Gynecol Sci, 2021; 64(1); 52-61

18.. Capone V, Persico N, Berrettini A, Definition, diagnosis and management of fetal lower urinary tract obstruction: Consensus of the ERKNet CAKUT-Obstructive Uropathy Work Group: Nat Rev Urol, 2022; 19(5); 295-303

19.. Stringer MD, Duplications of the alimentary tract: Pediatric surgery, 2020; 935-53, Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-43588-5_68

20.. Ni M, Zhu X, Liu W, Fetal congenital gastrointestinal obstruction: Prenatal diagnosis of chromosome microarray analysis and pregnancy outcomes: BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 2023; 23(1); 503

21.. Puri P, Höllwarth ME, Duplications of the Alimentary Tract: Pediatric surgery, 2023; 893-906, Switzerland AG, Springer Nature Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81488-5_66

22.. Ahmed O, Lee JH, Thompson CC, Faulx A, AGA Clinical practice update on the optimal management of the malignant alimentary tract obstruction: Expert review: Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021; 19(9); 1780-88

Figures

In Press

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943467

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943376

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250