03 August 2023: Articles

Rapidly Enlarging Parotid Mass in a Person Living with HIV: A Case of Multiple Myeloma with Extramedullary Plasmacytoma

Challenging differential diagnosis

Maria G. Novitskaya1ABEF, Peter A. DeRosa2DEF, David T. Chen3BE, Ahmed Khalil4BE, Omar Harfouch5BE, Erin E. O'Connor6DE, Sarah A. Schmalzle57AEF*DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.938431

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e938431

Abstract

BACKGROUND: The differential diagnosis for a parotid mass is broad, including infectious, autoimmune, and neoplastic etiologies. In people with HIV, regardless of viral suppression or immune status, neoplastic causes are more common. This report describes the evaluation of a woman with a large parotid mass, with an ultimate diagnosis of multiple myeloma with extramedullary plasmacytoma.

CASE REPORT: A 51-year-old woman with HIV infection presented with headache, weight loss, and right facial mass that was present for 5 years but more rapidly enlarging in the prior year. CD4 count was 234 cells/mL, and HIV RNA was 10 810 copies/mL. Physical examination was significant for a large deforming right-sided facial mass, decreased sensation in the V1 and V2 distributions, and right-sided ophthalmoplegia and ptosis. MRI and PET/CT scan confirmed a metabolically active large parotid mass with extension into the cavernous sinus. An IgG kappa monoclonal spike was present on serum protein electrophoresis. Incisional biopsy of the facial mass showed atypical lymphoid cells with plasmablastic and plasmacytic morphology with a high mitotic rate and proliferation index. She was diagnosed with R-ISS stage II IgG kappa multiple myeloma with extramedullary plasmacytoma, and initiated on chemotherapy, radiation, and antiretroviral therapy.

CONCLUSIONS: A rapidly enlarging parotid mass should prompt timely evaluation and biopsy for definitive diagnosis, particularly in immunocompromised patients, including people with HIV. Extramedullary plasmacytomas have a more aggressive disease process in people with HIV and are associated with high-risk multiple myeloma and progression, as seen in this patient.

Keywords: Cavernous Sinus, HIV, Multiple Myeloma, Neoplasm Metastasis, Parotid Diseases, Plasmacytoma, Female, Humans, Middle Aged, HIV Infections, Positron Emission Tomography Computed Tomography, Hypertrophy, Immunoglobulin G

Background

People living with HIV (PLWH) have a higher incidence of AIDS-defining cancers (ADC), including Kaposi sarcoma (KS), invasive cervical cancer, and several specific non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL), as well as a higher incidence of non-AIDS-defining cancers (NADC) [1]. Cancer incidence is highest in PLWH with low CD4 counts, low CD4/CD8 ratio, and HIV viremia, and lowest in the PLWH who have durable HIV viral suppression, though even the latter group still has excess cancer risk [2]. The higher prevalence of malignancies in PLWH may be explained by a higher risk of contracting oncogenic viruses, chronic antigen stimulation, inflammation, and cytokine dysregulation [3].

The case reported here presented with marked unilateral parotid enlargement. Parotid enlargement can stem from infections, autoimmune syndromes, and neoplasms. While parotid neoplasms can be benign or malignant, they are more commonly benign in both PLWH and HIV-uninfected patients, with higher rates of malignancy in PLWH than in HIV-uninfected patients [4,5]. Malignant neoplasms of the parotid gland more common in PLWH include Burkitt lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, plasmablastic lymphoma, and extramedullary plasmacytoma (EMP). EMPs can herald a diagnosis of multiple myeloma (MM), be co-diagnosed with MM, or can occur independently of MM [6], and can be associated with HIV [7]. Extramedullary disease is associated with high-risk MM and worse prognosis than in MM without extra-medullary disease, regardless of therapy. Treatment options for MM with EMP include chemotherapy and stem cell transplant. Patients with HIV who develop plasmacytomas tend to be younger, with more aggressive malignancies and a greater likelihood of having solitary extramedullary plasmacytomas [8].

Two reported cases of parotid EMP in PLWH include a 48-year-old woman concurrently diagnosed with HIV, MM, and EMP, and a 46-year-old woman compliant with antiretroviral therapy (ART) and diagnosed with MM and EMP [8,9]. The first case also had involvement of the oral cavity, maxilla, and paranasal sinuses, while the second case was limited to the parotid gland. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman with HIV infection diagnosed with parotid EMP and MM complicated by cavernous sinus syndrome, after developing deforming unilateral parotid enlargement, headaches, weight loss, and ophthalmoplegia.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer, recent acute-onset heart failure with reduced ejection fraction of <15% following a self-reported “cold”, ie, upper respiratory infection, ablated Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, depression, and HIV presented with an enlarging right facial mass (Figure 1), headaches, and 40-pound (18 kg) weight loss. Stage II invasive ductal carcinoma of the outer quadrant of the right breast was diagnosed 6 years prior and was treated with quadrantectomy and lymph node dissection, radiation therapy, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy including doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide later followed by trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and docetaxel. The patient was ultimately lost to follow-up with her oncologist. At the time of presentation, she reported slow enlargement of the facial mass over 5 years with more rapid growth over the past year. She had not taken any prescribed medications or sought any in-person medical care for over a year at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, due to her fear of contracting this infection. A fine-needle aspirate 3 months prior had scant cellularity but revealed an atypical population of lymphocytes with plasmacytoid morphology, variably open chromatin, and variably conspicuous nucleoli.

Physical examination was significant for a large deforming right pre-auricular facial mass with purple discoloration, decreased sensation in the right V1 and V2 distribution, and right-sided complete ophthalmoplegia, anisocoria, and ptosis. A right-sided parotid mass with intracranial extension into the cavernous sinus was confirmed on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 2). PET/CT scan showed a hypermetabolic 9.0 by 7.7 cm parotid mass with a maximal standardized uptake value of 16.8, in addition to metabolically active lesions in the right cavernous sinus extending to the right orbit and sella turcica, cervical lymph nodes, bilateral femurs, and left tibia, as well as a lytic lesion in the distal right femur. Additional evaluation revealed elevated IgG at 5326 mg/dL (normal range 6–16), elevated free kappa chain of 100.17 mg/L (normal range 3.3–19.4), free lambda chain of 15.45 mg/L (normal range 5.71–26.3), and elevated kappa to lambda ratio of 6.48 (normal range 0.26–1.65). Serum protein electrophoresis showed an IgG kappa monoclonal spike with an M-spike of 3.94. Mild plasmacytosis without a monotypic population was seen on bone marrow biopsy. Cerebrospinal fluid cytology was unremarkable. HIV RNA was 10 810 copies/mL and the absolute CD4 count was 234 cells/mL.

The patient underwent an incisional parotid mass biopsy, which revealed an infiltrative tumor consisting of a monotonous population of large atypical lymphoid cells with open chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and a moderate amount of pale blue cytoplasm. Salivary gland tissue was not identified within the tumor. The atypical cells showed plasmacytic as well as plasmablastic morphology and a high mitotic rate (Figure 3).

Based on cytomorphology, the differential diagnosis was broad and included plasmablastic extramedullary plasmacytoma, plasmablastic lymphoma NOS, plasmablastic lymphoma (oral type), extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), blastic mantle cell lymphoma, and ALK-positive diffuse large B cell lymphoma and less likely, marginal zone lymphoma, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Given the patient’s immunocompromised status, high serum monoclonal protein, negative quantitative serum PCR for EBV, and results of immunohistochemical findings, the diagnosis was narrowed to plasmablastic extramedullary plasmacytoma and plasmablastic lymphoma. The tumor cells showed negativity for EBER (Epstein-Barr encoding region) by in-situ hybridization. Expression of CD138, MUM1, and Cyclin-D1 in combination with negativity for EBER favored a diagnosis of plasma-blastic extramedullary plasma cell neoplasm.

A diagnosis of MM was made simultaneously with the extramedullary plasmacytoma diagnosis. Based on the revised American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines for the diagnosis of MM, the patient was ultimately diagnosed with R-ISS stage II IgG kappa MM with extramedullary plasmablastic neoplasm. In evaluation of the “CRAB” criteria (Calcium, Renal insufficiency, Anemia, Bone lesions) the patient presented with anemia (hemoglobin of 9.4 g/dL) and a lytic lesion in the femur (qualifying the patient as having 2 “CRAB” criteria). The patient did not demonstrate hypercalcemia or renal insufficiency. In addition, right cavernous sinus syndrome was diagnosed based on the lesion along the right cavernous sinus with extension into the right orbit and sella turcica on imaging, and ptosis, anisocoria, and total ophthalmoplegia on physical examination.

The patient underwent local radiotherapy to the facial mass and was initiated on chemotherapy with bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for 6 cycles, with a plan for autologous stem cell transplant after induction. Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) with a single-tablet regimen containing bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide was resumed and she was counseled on the importance of daily adherence. Three months later, CD4 had risen to 771 cells/mL and HIV RNA had dropped to 79 copies/mL. As of 7 months following the initiation of cancer treatment, the parotid mass is unnoticeable, and the patient no longer has ophthalmoplegia. Despite this, she has developed a new mass in her left breast, which was diagnosed as plasmacytoma on biopsy. The patient’s new plasmacytoma is a manifestation of extended disease, likely due to her MM becoming chemotherapy resistant. Autologous stem cell transplant has not yet been performed but transplant options are currently being considered.

Discussion

This case highlights the myriad disease states that can present with parotid involvement, the elevated cancer risk in people living with HIV, and the aggressive and atypical presentations that can occur in immunocompromised patients.

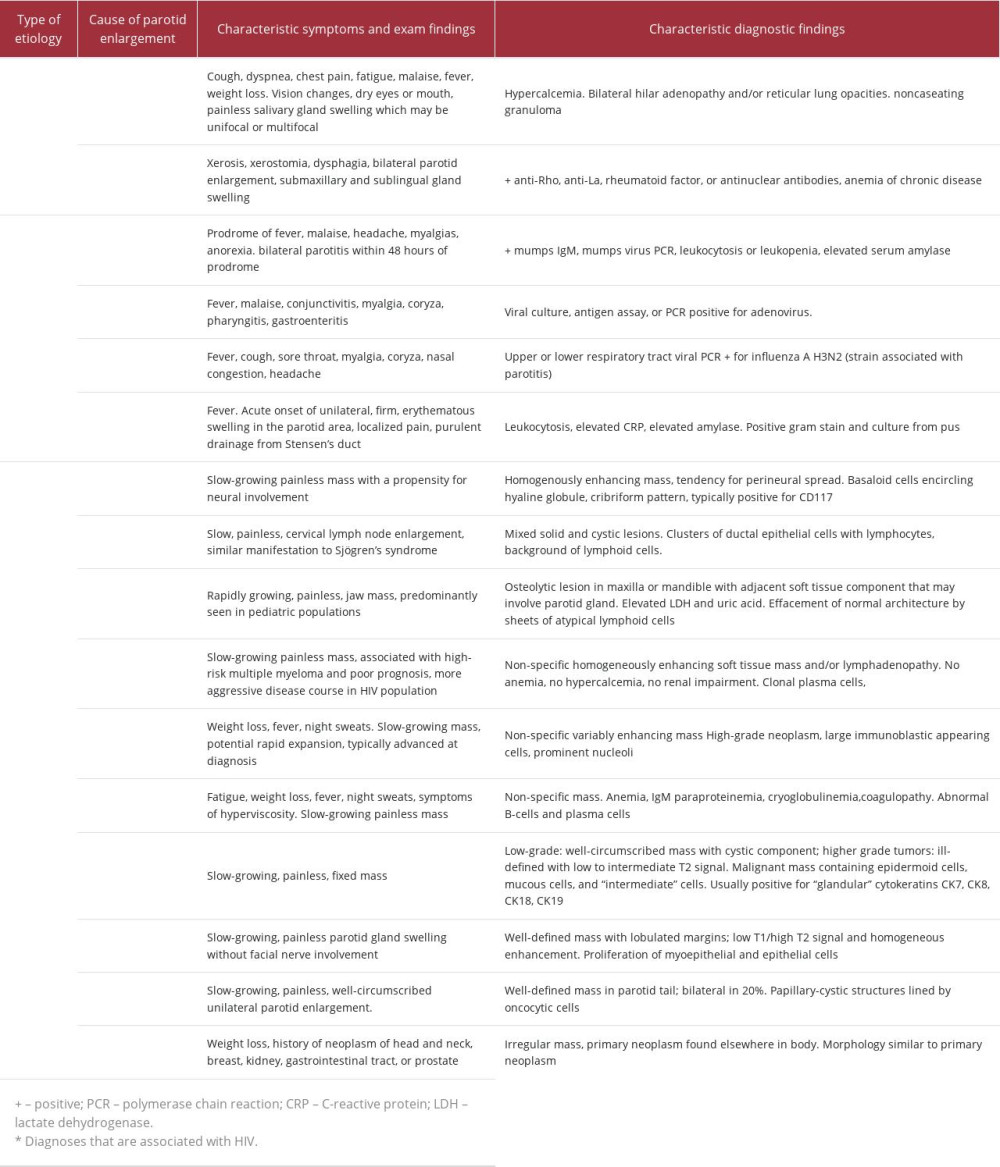

Proper evaluation of a parotid mass includes consideration of and evaluation for autoimmune, infectious, and neoplastic etiologies (Table 1) [10–30]. In light of the marked destruction of the parotid gland and the HIV status of this patient, common infectious and autoimmune causes were quickly eliminated as likely etiologies, in favor of several of the more-aggressive malignancies.

Immunohistochemical stains showed that the atypical cells were positive for CD45, CD138, MUM-1, CD79a, CD20, CD10, IgG, kappa light chains, Cyclin-D1, BCL2, and CD33 (Figure 4). Ki-67 immunohistochemical staining showed a high proliferation index of 80%. The atypical lymphoid cells were negative for CD19, PAX5, BCL6, CD30, IgA, IgM, IgD, lambda light chains, HHV8, c-MYC, TP53, Sox 11, ALK1, EMA, and CD43. CD21 did not identify any dendritic cell meshwork. CD3 and CD5 show similar staining patterns and highlighted scattered background T cells. In-situ hybridization for EBER (Epstein-Barr encoding region) was negative. Given the high proliferative index and plasmablastic morphology, marginal zone and MALT lymphoma were not favored. Blastic mantle cell lymphoma was virtually excluded due to negativity for SOX-11 and CD5. Extracavitary PEL was excluded due to negativity for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). ALK-1 negativity excluded ALK-1 positive diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The absence of serum EBV and EBER staining in an immuno-compromised patient with high serum monoclonal protein further narrowed the diagnosis to plasmablastic extramedullary plasmacytoma and plasmablastic lymphoma, 2 diagnoses that are potentially occurring along a spectrum, and which have significant immunohistochemical overlap [31–33]. The patient’s tumor cells showed negativity for EBER by in-situ hybridization. Expression of CD138, MUM1, and Cyclin-D1 in combination with negativity for EBER favored a diagnosis of plasma-blastic extramedullary plasma cell neoplasm.

There are several unique aspects of this case that could relate to the patient’s significant immune suppression and her delayed presentation to care, which occurred in the setting of restricted appointment access and patient fears during the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, this patient presented with markedly abnormal parotid gland distortion from the aggressive extramedullary plasma-cytoma, with the MM diagnosis occurring only in the course of further evaluation to establish the diagnosis of the parotid gland tumor. Typically, extramedullary plasmacytomas are discovered during evaluation of a new MM diagnosis, with rates of detection increasing with more modern diagnostic imaging modalities [6].

Additionally, cavernous sinus involvement from a parotid tumor is uncommon; it has been documented in adenoid cystic carcinoma [35], Burkitt lymphoma [36], extramedullary plasmacytoma [37], lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma [38], mucoepidermoid carcinoma [39], and pleomorphic adenoma [40]. There have been fewer than 30 cases of plasmacytoma with cavernous sinus involvement reported in the literature [41], making this a rare presentation.

Lastly, this patient had a slow-growing parotid mass for multiple years before a rapid and aggressive increase in size occurred.

This pattern of slow then rapid growth has been noted in cases of plasmablastic lymphoma as well, adding to the complexity of distinguishing these 2 closely presenting entities [31,32,42].

Conclusions

A rapidly enlarging parotid mass, especially in a person living with HIV, must prompt timely evaluation with greater consideration for malignant etiologies, which are more common in this population. Extramedullary plasmacytomas behave more aggressively in people living with HIV and are associated with high-risk multiple myeloma and progression, as seen in this patient. Treatment with cART, general cancer prevention counseling, cancer screening, and prompt evaluation of suspicious findings are critically important in the care of people living with HIV.

Figures

References:

1.. Shiels MS, Cole SR, Kirk GD, Poole C, A meta-analysis of the incidence of non-AIDS cancers in HIV-infected individuals: J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2009; 52(5); 611-22

2.. Castilho JL, Bian A, Jenkins CA, CD4/CD8 ratio and cancer risk among adults with HIV.: J Natl Cancer Inst., 2022; 114(6); 854-62

3.. Berhan A, Bayleyegn B, Getaneh Z, HIV/AIDS associated lymphoma: Review: Blood Lymphat Cancer, 2022; 12; 31-45

4.. Thielker J, Grosheva M, Ihrler S, Contemporary management of benign and malignant parotid tumors: Front Surg, 2018; 5; 39

5.. Grulich AE, van Leeuwen MT, Falster MO, Vajdic CM, Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: A meta-analysis: Lancet, 2007; 370(9581); 59-67

6.. Varettoni M, Corso A, Pica G, Incidence, presenting features and outcomes of extramedullary disease in multiple myeloma: A longitudinal study on 1003 consecutive patients: Ann Oncol, 2010; 21; 325-30

7.. Coker WJ, Jeter A, Schade H, Kang Y, Plasma cell disorders in HIV-infected patients: Epidemiology and molecular mechanisms: Biomark Res, 2013; 1(1); 8

8.. Feller L, White J, Wood NH, Extramedullary myeloma in an HIV-seropositive subject. Literature review and report of an unusual case.: Head Face Med, 2009; 5; 4

9.. Maharaj S, Mungul S, Initial manifestation of parotid extra-medullary myeloma in an HIV positive patient on anti-retroviral therapy: A case report and review of the literature: Biomed Rep, 2020; 13(4); 28

10.. Sève P, Pacheco Y, Durupt F, Sarcoidosis: A clinical overview from symptoms to diagnosis: Cells, 2021; 10(4); 766

11.. Mavragani CP, Moutsopoulos HM, Sjögren syndrome: CMAJ, 2014; 186(15); E579-86

12.. Pijpe J, Kalk WWI, Bootsma H, Progression of salivary gland dysfunction in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: Ann Rheum Dis, 2007; 66(1); 107-12

13.. Zhou JG, Qing YF, Jiang L, Clinical analysis of primary Sjögren’s syndrome complicating anemia: Clin Rheumatol, 2010; 29(5); 525-29

14.. Hviid A, Rubin S, Mühlemann K, Mumps: Lancet, 2008; 371(9616); 932-44

15.. Khanal S, Ghimire P, Dhamoon A, The repertoire of adenovirus in human disease: The innocuous to the deadly: Biomedicines, 2018; 6(1); 30

16.. Blut A, Influenza virus: Transfus Med Hemother, 2009; 36(1); 32-39

17.. Rolfes MA, Millman AJ, Talley P, Influenza-associated parotitis during the 2014–2015 influenza season in the United States: Clin Infect Dis, 2018; 67(4); 485-92

18.. Brook I, Acute bacterial suppurative parotitis: Microbiology and management: J Craniofac Surg, 2003; 14(1); 37-40

19.. Sujata DN, Subramanyam SB, Jyothsna M, Pushpanjali M, Adenoid cystic carcinoma: An unusual presentation: J Oral Maxillofac Pathol, 2014; 18(2); 286

20.. Jeong HS, Lee HK, Ha YJ, Benign lymphoepithelial lesion of parotid gland and secondary amyloidosis as concurrent manifestations in Sjögren’s syndrome: Arch Plast Surg, 2015; 42(3); 380

21.. Kalisz K, Alessandrino F, Beck R, An update on Burkitt lymphoma: A review of pathogenesis and multimodality imaging assessment of disease presentation, treatment response, and recurrence: Insights Imaging, 2019; 10(1); 56

22.. Turro J, Singh P, Sarao MS, Adult Burkitt lymphoma – an Island between lymphomas and leukemias: J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect, 2019; 9(1); 25-28

23.. Soutar R, Lucraft H, Jackson G, Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of solitary plasmacytoma of bone and solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma: Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol), 2004; 16(6); 405-13

24.. Bhatt R, Desai DS, Plasmablastic lymphoma. [Updated 2022 Apr 14].: StatPearls [Internet]., 2023, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing

25.. Moramarco A, Marenco M, La Cava M, Lambiase A, Radiological-pathological correlation in plasmablastic lymphoma in an immunocompromised patient.: Case Rep Ophthalmol Med., 2018; 2018; 4746050

26.. Fang H, Kapoor P, Gonsalves WI, Defining lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma.: Am J Clin Pathol, 2018; 150(2); 168-76

27.. Boahene DKO, Olsen KD, Lewis JE, Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the parotid gland: The Mayo clinic experience: Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2004; 130(7); 849

28.. Almeslet AS, Pleomorphic adenoma: A systematic review: Int J Clin Pediatr Dent, 2020; 13(3); 284-87

29.. Tartaglione T, Botto A, Sciandra M, Differential diagnosis of parotid gland tumours: Which magnetic resonance findings should be taken in account?: Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital, 2015; 35(5); 314-20

30.. Jung HK, Lim YJ, Kim W, Breast cancer metastasis to the parotid: A case report with imaging findings.: Am J Case Rep., 2021; 22; e934311

31.. Qing X, Sun N, Chang E, Plasmablastic lymphoma may occur as a high-grade transformation from plasmacytoma: Exp Mol Pathol, 2011; 90(1); 85-90

32.. Boy SC, van Heerden MB, Raubenheimer EJ, van Heerden WF, Plasmablastic lymphomas with light chain restriction – plasmablastic extramedullary plasmacytomas?: J Oral Pathol Med, 2010; 39(5); 435-39

33.. Vega F, Chang CC, Medeiros LJ, Plasmablastic lymphomas and plasmablastic plasma cell myelomas have nearly identical immunophenotypic profiles: Mod Pathol, 2005; 18(6); 806-15

34.. : Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV, 2023, Department of Health and Human Services Available at Accessed 4/2/2023https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv

35.. Dzięciołowska-Baran E, Gawlikowska-Sroka A, Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the cavernous sinus – otolaryngological sequelae of therapy: case report.: Adv Exp Med Biol, 2018; 1040; 23-27

36.. Jakubowska W, Chorfi S, Bélanger C, Childhood Burkitt lymphoma manifesting as cavernous sinus syndrome: Can J Ophthalmol, 2022; 57(1); e22-e24

37.. Broek IV, Stadnik T, Meurs A, Extramedullary plasmacytoma of the cavernous sinus: Leuk Lymphoma, 2002; 43(8); 1691

38.. Pham C, Griffiths JD, Kam A, Hunn MK, Bing-Neel syndrome – bilateral cavernous sinus lymphoma causing visual failure: J Clin Neurosci, 2017; 45; 134-35

39.. Roos JC, Beigi B, Lacrimal sac mucoepidermoid carcinoma with metastases to the cavernous sinus following dacryocystorhinostomy treated with stereotactic radiotherapy: Case Rep Ophthalmol, 2016; 7(1); 274-78

40.. Chen HH, Lee LY, Chin SC, Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma of soft palate with cavernous sinus invasion: World J Surg Oncol, 2010; 8; 24

41.. Lakhdar F, Arkha Y, Derraz S, [Solitary intrasellar plasmocytoma revealed by a diplopia: A case report.]: Neurochirurgie, 2012; 58(1); 37-39 [in French]

42.. Bishop JA, Westra WH, Plasmablastic lymphoma involving the parotid gland: Head Neck Pathol, 2010; 4(2); 148-51

Figures

In Press

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943467

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943376

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250