30 September 2023: Articles

Pimavanserin Treatment for Psychosis in Patients with Dementia with Lewy Bodies: A Case Series

Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment

Kasia Gustaw Rothenberg1ABDEF, Sharon G. McRae23BE, Liza M. Dominguez-Colman24BE, Andrew Shutes-David23DEF, Debby W. Tsuang24ABDE*DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.939806

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e939806

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Many patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) experience cholinesterase inhibitor- and antipsychotic-resistant psychosis. The new second-generation antipsychotic pimavanserin has been used with some success in the treatment of psychosis in other forms of dementia, including Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease dementia. It is possible that pimavanserin may also be useful in the treatment of psychosis in DLB. We sought to describe the disease course and treatment of psychosis in 4 patients with DLB who were prescribed pimavanserin after other medications failed to reduce the frequency or severity of hallucinations and delusions.

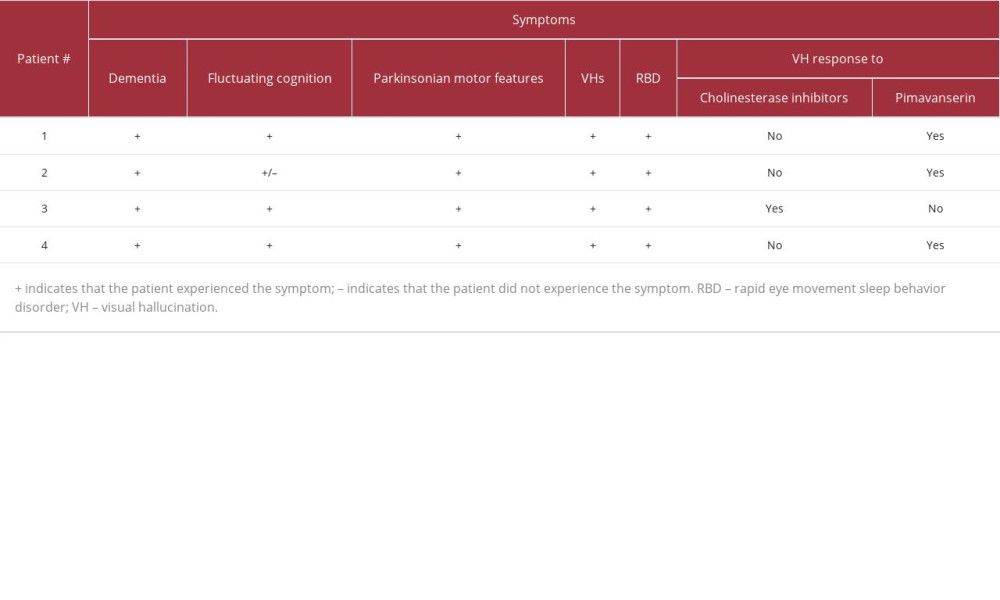

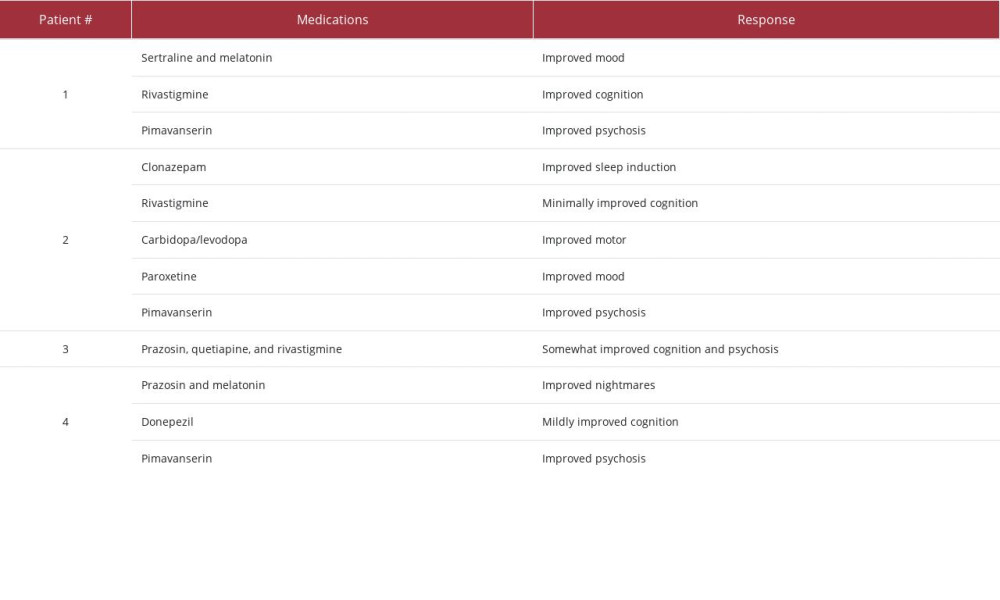

CASE REPORT: This is a case series of 4 male patients (ages 56 to 74 at the beginning of the reports) who developed DLB and psychosis (eg, visual illusions, visual and olfactory hallucinations, and paranoid delusions). All 4 patients were prescribed cholinesterase inhibitors (eg, donepezil or rivastigmine) prior to pimavanserin, and only 1 patient experienced improved psychosis while on cholinesterase inhibitors. All 3 patients who were prescribed first-generation antipsychotics (eg, haloperidol) or traditional second-generation antipsychotics (eg, olanzapine, risperidone, or quetiapine) experienced initial or lasting side effects with no improvement of psychosis. Conversely, all 4 patients tolerated pimavanserin well, and 3 of the 4 patients experienced significant improvement of psychosis (eg, fewer hallucinations, fewer delusions, reduced paranoia, and/or reduced distress or agitation related to hallucinations and delusions) when prescribed pimavanserin.

CONCLUSIONS: This case series suggests that pimavanserin is tolerable in older males with DLB and that it may be useful for the reduction of distressful hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia in patients with DLB.

Keywords: Delusions, Hallucinations, Lewy Body Disease, Dementia, Parkinsonian Disorders, Pimavanserin, Humans, Male, Aged, Antipsychotic Agents, Dementia, Cholinesterase Inhibitors, Parkinson Disease, Psychotic Disorders, Piperidines, Urea

Background

Patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) are frequently only diagnosed after many clinician visits and years of symptoms [1,2], in part because of the complex clinical manifestations of DLB [3], which can include distressing visual hallucinations [4]. These hallucinations tend to be well formed, occur at night, and are accompanied by delusions in the later stages of the disease [3]. In other psychotic disorders, like schizophrenia, the dopaminergic system appears to be the primary neurochemical system contributing to hallucinations, but in DLB the pathophysiology of psychosis is most likely multifactorial, and this can complicate treatment efforts. To that end, cholinesterase inhibitors (eg, donepezil and rivastigmine) [5–9] and/or second-generation antipsychotics (eg, quetiapine and clozapine) [3,10–13] can reduce symptoms of psychosis in some patients with DLB, but many others continue to experience visual hallucinations or to experience side effects that prevent successful administration of the medications. Novel antipsychotics that have new mechanisms of action and that lack a dopamine receptor’s binding property may prove more effective for at least a subset of these cholinesterase inhibitor- or antipsychotic-resistant patients.

Pimavanserin, for example, is a selective serotonin inverse agonist of 5-HT2A receptors; that is, it is a second-generation antipsychotic that does not bind to dopaminergic receptors and may avoid the motor and sedative adverse side effects of other antipsychotics [14]. In a clinical trial of patients with Alzheimer disease (AD) and psychosis, there was a 6-month reduction in psychosis but not a 12-month reduction [15]. The same research team then demonstrated 12-month efficacy for pimavanserin in patients with AD and higher baseline severity of psychotic symptoms [16]. Likewise, in Parkinson disease (PD), treatment with pimavanserin has reduced the number and severity of hallucinations and delusions without worsening parkinsonism [17,18], and it has been approved as a treatment by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for PD dementia (PDD)-related psychosis since 2016.

Studies that evaluate pimavanserin as a treatment for psychosis in AD, PD, and other neurodegenerative disorders are valuable, but DLB is the only common neurodegenerative disorder in which visual hallucinations are a core diagnostic criterion [4] and in which around 75% of patients experience psychosis [9]. Yet despite the prominence of psychosis in DLB and the potential of pimavanserin, there are few reports that clearly describe the course of patients with DLB who use pimavanserin to treat psychosis. Therefore, here we share a case series to offer additional context on the potential use of pimavanserin in patients with DLB who present with drug-resistant psychosis.

Case Report

Patient #1

EARLY DISEASE COURSE:

At age 71, this male patient exhibited slower reaction times and was observed acting out his dreams. He was diagnosed by polysomnography with rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD). Soon after the RBD diagnosis, he began experiencing increased anxiety and depressed mood. His gait changed, his movements slowed, and he was identified as having orthostatic hypotension. In addition, the patient’s

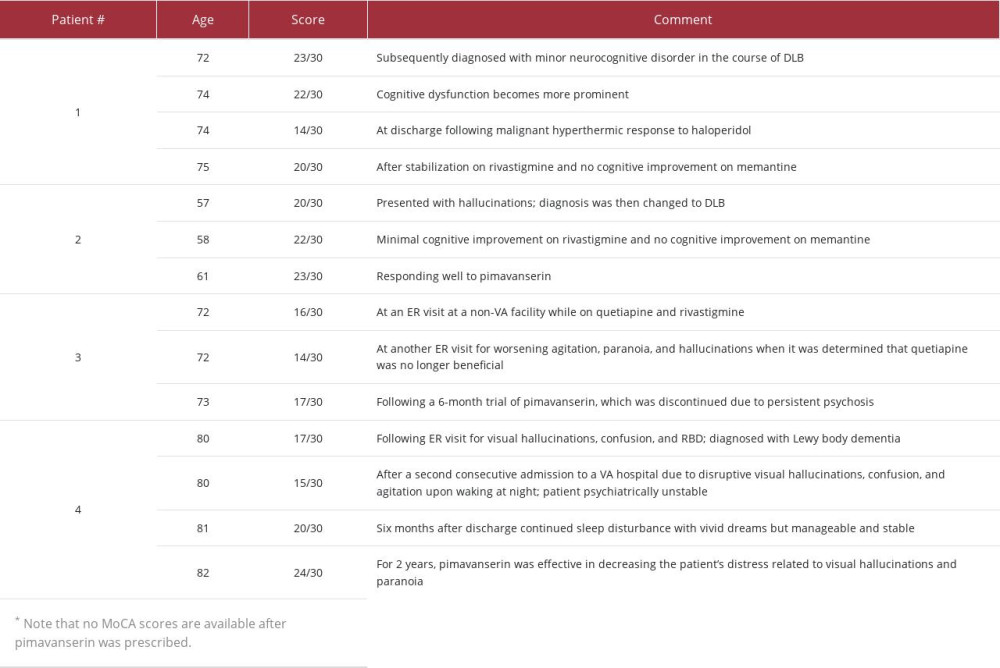

caregiver observed a change in personality, namely that he had become increasingly possessive. She also noticed that he had increased difficulty preparing his income tax returns, responding to emails, and recalling conversations. On neurological evaluation at age 72, bradykinesia and stooped gait were reported, and the patient scored 23 on the MoCA. He was then diagnosed with minor neurocognitive impairment in the course of DLB, and treatment with melatonin and sertraline was initiated with initial improvement in mood.

ONSET OF PSYCHOSIS:

At age 74, the patient’s cognitive dysfunction was more prominent; he scored 22 on the MoCA, and he could no longer judge chip shots or putts when golfing. After surgery for a torn quad-riceps tendon, he developed prolonged delirium with visual illusions and hallucinations. For instance, the patient repeatedly asked his caregiver about the ocean outside his hospital window or about a group of men repairing a nearby roof, but the room lacked an ocean or rooftop view. Over time, the patient’s gait slowed, his posture stooped, and he started experiencing more prominent orthostatic symptoms. The patient received levodopa to address parkinsonian symptoms, but it induced more severe episodes of hallucinations, and the medication was discontinued. Well-formed hallucinations continued to reoccur infrequently and without any trigger.

RESPONSE TO TREATMENTS:

The patient underwent hip replacement surgery at age 74. The succinylcholine administered preoperatively caused a malignant hyperthermic response, and 2 doses of haloperidol (1 mg) administered postoperatively induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome (fever, muscle rigidity, diaphoresis, tachycardia). The patient was treated in the intensive care unit (with intubation, dantrolene), and his recovery was prolonged. At discharge from the rehabilitation center, his cognitive function had declined significantly, and he scored 14 on the MoCA.

The patient continued experiencing visual illusions, misidentifications, and frank hallucinations. Then, at age 75, he received rivastigmine and experienced cognitive improvement, including improved planning, sequencing, and all aspects of language, including articulation. These improvements were most noticeable after titration of the dose to 9.4 mg and then again to 13.3 mg. However, no improvement was observed in the severity and frequency of visual misidentifications and hallucinations. A trial of memantine did

RESPONSE TO PIMAVANSERIN:

Following the trial of memantine, pimavanserin was started at a dose of 34 mg, and the patient and caregiver reported that he experienced significantly fewer hallucinations. It took 3 months to ensure that the changes were consistently occurring because the patient presented with marked daily fluctuations in cognition and behavior. That said, the patient seemed to better tolerate these fluctuations, and his caregiver opined that the patient now “self-regulates his highs and lows better.” With the exception of 1 episode, when there was a change in mental status due to a urinary tract infection, the caregiver also observed a decrease in the occurrence of delusions. The patient’s cognitive dysfunction remains at the same level.

EARLY DISEASE COURSE:

At age 56, this male patient was diagnosed with RBD after he noticed his lower right arm bending up toward his abdomen in a “gun slinger” pose and his wife observed that his sleep appeared restless. The patient began experiencing atypical anxiety with a depressed mood, as well as micrographia, brady-kinesia, shuffling gait, hyposmia, and episodes of orthostatic hypotension. He soon struggled to multitask, manage work responsibilities, and perform activities of daily living, including teeth brushing, packing a lunch, remembering his wallet and eyeglasses, and grabbing his keys before driving. He was diagnosed with PD and initially treated with carbidopa/levodopa, paroxetine, rivastigmine, and clonazepam.

ONSET OF PSYCHOSIS:

Symptoms of cognitive impairment and psychosis were noticeable and concomitant with the patient’s motor symptoms. At age 57, the patient scored 20 on the MoCA and presented with hallucinations of little girls having tea parties, bugs crawling on the floor, and a bear in the backyard. These symptoms led to a reevaluation and a change in diagnosis to DLB. Nevertheless, the patient continued to work as an investigative reporter and editor, played full-court basketball once a week, and started a basketball tournament to raise money for DLB research. His bradykinesia gradually increased, and he developed more severe anxiety and depression, as well as a decline in executive functioning. His hallucinations and delusions gradually became more pronounced.

RESPONSE TO TREATMENTS:

The patient experienced minimal cognitive improvement after optimization of his rivastigmine dose (ie, he scored 22 on the MoCA), but the addition of memantine had no effect. His motor symptoms improved in response to the carbidopa/levodopa, and his depression remitted, partially in response to the paroxetine.

The patient’s caregiver initially sought to address his psychosis nonpharmacologically by minimizing stimulation and teaching him to “send” the scary hallucinations away so that he could feel safe. However, his hallucinations and delusions worsened, his fears progressed to terror, and these symptoms did not respond to trials of quetiapine (increased titration to 150 mg), olanzapine (10 mg), or risperidone (2 mg). Moreover, the antipsychotics appeared to worsen his motor symptoms, and he began experiencing paranoid delusions and visual, auditory, and olfactory hallucinations. The patient was observed listening to trees that he said walked around their yard or talking to people who appeared in his home through a series of imaginary tunnels. These people would morph into cartoons and disappear into walls. Others would morph into fish, and he could smell them in the beds. When he believed these people were trying to harm his family, the patient would attack the bedding and throw it down the stairs. At other times, he believed the coat racks were people who needed help – they were poor and hungry – so the patient would pull food out of the pantry to feed them. He also believed he was starring in a DLB research film and that activities at his house were being recorded for the film. He began pacing around rooms, distrusting his family and friends.

RESPONSE TO PIMAVANSERIN:

A dose of 34 mg pimavanserin was initiated at age 60, 4 years after the patient’s initial symptoms were documented. Within 2 weeks, the patient’s hallucinations dramatically reduced, and the patient’s family reported that he had “come back” out of psychosis. Four weeks after beginning pimavanserin, the patient began writing articles again and communicating with family and friends. One year later, at age 61, the patient was still responding well to treatment with pimavanserin, and his cognition remained at the same level (ie, a MoCA score of 23).

EARLY DISEASE COURSE:

This male patient was first diagnosed with DLB at age 71, but it is likely that his symptoms began more than 10 years earlier and were misattributed to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression, for which he received buspirone and fluoxetine, 2 medications that were later discontinued at age 71. At age 61, the patient was seen by a Veterans Affairs (VA) psychiatrist for treatment related to insomnia and self-medicating with alcohol, which he discontinued by age 68 following hospitalization for a pulmonary embolism. From age 63 to 67, he reported increasing anxiety and hypervigilance, including scanning public areas for exits and escape routes, feeling unease when socializing with family members, and switching to a lower-paying job to avoid the stress of working around others. At age 65, he experienced night terrors after falling out of bed, shouting, and responding to violent dreams by placing his hands around his wife’s neck. The patient’s wife reported some minor forgetfulness, word-finding difficulties, mild hand tremors, and slowed movements. At age 68, the patient indicated that he saw someone hiding outside the house, and he remarked that the home seemed crowded. He also became more anxious, and his ability to recall what he heard, engage in conversations, and manage medications declined. By age 69, he had stopped driving due to fluctuations in cognition and a worsening resting tremor in his hands. Finally, at age 71, after the clear onset of hallucinations (see next section), the patient was diagnosed with DLB. The neurological assessment confirmed RBD, loss of olfaction, confusion, forgetfulness, word-finding difficulties, and slow movements with a shuffling gait.

ONSET OF PSYCHOSIS:

At age 61, the patient described fire hydrants and other inanimate objects taking on the appearance of humans, and at age 63, he recalled “freaking out” after seeing things move that others did not see. However, the patient and his wife attributed these symptoms to PTSD-related hypervigilance. Then, at an appointment at age 71, the patient was diagnosed with DLB after describing visual hallucinations of humans who were not there and associating his dog with a sign of death. Over time, his paranoid delusions, visual hallucinations, and olfactory hallucinations worsened, and other symptoms included word-finding difficulties, confusion, periods of forgetting names and surroundings, and detailed nightmares that resulted in sleep disturbances.

RESPONSE TO TREATMENT:

The patient was prescribed 1 mg prazosin at bedtime for night terrors but opted for an herbal remedy and self-medication with alcohol. He was also prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and melatonin for trauma-related symptoms.

After the initial diagnosis of DLB at age 71, the patient was prescribed quetiapine 50 mg 3 times a day and rivastigmine 3 mg at bedtime. During an emergency room (ER) visit at a non-VA facility, the patient scored 16/30 on the MoCA. The quetiapine was thought to cause significant somnolence, but the patient’s wife opted to continue the medication, as she found the psychosis and related agitation more challenging as a caretaker.

The patient’s sleep improved, but the agitation and hallucinations worsened. The patient reported seeing a person crawl then initiated, which resulted in a paradoxical reaction: excessive sedation, screaming at night, incoherence, and an inability to perform activities of daily living the following morning. Quetiapine was discontinued, which resulted in rapid resolution of the medication-related symptoms. One week later, the patient was hospitalized again due to disruptive visual hallucinations, confusion, and agitation upon waking at night.

Later that year, donepezil was initiated. The patient reported muscle spasms during the first week, but the spasms abated and the patient experienced improvements – particularly following dose titration to 5 mg and then 10 mg – in his executive functioning (eg, planning and sequencing and articulating ideas). However, no improvements in hallucinations were noted as a result of the donepezil.

RESPONSE TO PIMAVANSERIN:

During the patient’s first psychiatric admission at age 80 (see description above), pimavanserin 10 mg was started given that quetiapine and risperidone were ineffective, and the patient’s cognition improved to close to baseline levels. When he was readmitted less than 1 week later, he scored 15/30 on the MoCA. During this second psychiatric admission, pimavanserin was titrated up to 20 mg daily for visual hallucinations, and he was discharged to a memory care facility. Six months after discharge from the second hospitalization, he continued experiencing sleep disturbances with vivid dreams, but otherwise his symptoms were manageable and stable, and he scored 20/30 on the MoCA. One year later, at age 81, the patient reported having a good mood, appetite, and energy level with decreased concerns related to cognition or hallucinations. He was able to perform some activities of daily living without assistance, and he had improved sleep with vivid dreams but no agitation. Although he continued to experience hallucinations, they no longer bothered him or caused agitation or nighttime behaviors. For 2 years, pimavanserin was effective in decreasing the patient’s distress related to visual hallucinations and paranoia, and his cognition continued to improve (eg, he scored 24/30 on the MoCA). In March 2022, the patient’s hallucinations became more vivid, and pimavanserin was increased to 34 mg with a good response.

Discussion

As we have shown, the patients in our case series presented with cholinesterase inhibitor- and antipsychotic-resistant psychosis. Neurochemical analyses of the temporal cortex have found significant differences between patients with DLB who are and are not hallucinating in choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) enzymes, serotonergic receptor binding, dopamine metabolites, and serotonin metabolites, suggesting that an imbalance between monoaminergic and cholinergic transmitters may be involved in hallucinogenesis in DLB and/or that the disruption of serotonin and acetylcholine neurotransmissions may play a role [5,9]. In clinical trials and smaller studies, donepezil [6] and rivastigmine [7] have shown some success in reducing visual hallucinations and/or delusions in DLB [8]. Nevertheless, 2 of the 3 patients who received rivastigmine in our case report experienced cognitive improvement but no reductions in psychosis, whereas the third patient had a more complicated course in which rivastigmine with quetiapine initially led to an increase in hallucinations but later resulted in continued visual hallucinations that did not interfere with activities of daily living or psychiatric stability.

Patients with DLB and severe pharmacotherapy-resistant psychotic symptoms may benefit from somatotherapies like electroconvulsive therapy or transcranial magnetic stimulation [19]. First-generation antipsychotics offer another potential treatment, but they are generally contraindicated in DLB due to increasing parkinsonism, increased mortality risk, and significant deterioration of motor symptoms [20], sedation, and cognitive impairment. Even if they are effective, first-generation anti-psychotics should not be used indefinitely [21]. In our case report, 1 patient received haloperidol following a surgery, which induced a neuroleptic malignant syndrome response followed by increased cognitive impairment, anxiety, and aggression.

Second-generation antipsychotics may have a more favorable mechanism of action given that they have less dopaminergic impact. Nevertheless, the potential benefits of second-generation antipsychotics must always be weighed against any increased risks, such as increased risks of cerebrovascular accidents or mortality [22]. Olanzapine, for example, appears to have only limited value in reducing psychiatric symptoms in DLB [23], and risperidone does not appear to be beneficial [20]. Conversely, quetiapine and clozapine may be better tolerated and more useful [3], but no definitive randomized controlled trials clearly support their effectiveness for DLB [10,11], so their expected efficacy is partly based on extrapolation of results from PD studies [12]. Moreover, clozapine includes side effects like drooling, sedation, tremors, constipation, and delirium [13], and due to the risk of agranulocytosis, it requires blood monitoring [12].

In our case study, 1 patient received olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine to treat visual hallucinations, which appeared to trigger paranoid delusions and worsening hallucinations and motor symptoms. Another patient received risperidone and quetiapine and experienced increased anxiety and aggression with no change in psychosis, as well as side effects when quetiapine was administered at night. A third patient experienced increased agitation and hallucinations when receiving quetiapine in combination with rivastigmine, but these symptoms later appeared to recede to baseline levels and become less unsettling. None of the patients experienced a reduction in their visual hallucinations while on these second-generation antipsychotics.

Several of the patients experienced side effects when receiving second-generation antipsychotics, which suggested they may have fared better with an antipsychotic that lacked a dopamine receptor’s binding property, and 3 of the 4 patients experienced a stable decrease in visual hallucinations after receiving pimavanserin (see Table 1). At least 1 of these patients experienced a related decrease in delusions, and at least 2 of these patients were able to return to their regular activities.

We must develop therapies to treat the range of symptoms that are associated with DLB, but few clinical studies have looked specifically at psychosis in elderly cognitively impaired populations, and patients with DLB are typically excluded from drug trials of antipsychotics and psychotropics [24]. This means we have to extrapolate from trials of psychotropic agents in idiopathic psychiatric disorders [24,25]. The extension of these therapies to patients with DLB is thus based on untested assumptions and may lead to efficacy or tolerability issues. For example, while preparing this review, we only found 1 manuscript that specifically focused only on DLB, a case report that described a patient with DLB whose hallucinations responded to pimavanserin but who discontinued it due to financial concerns (ie, the patient had a large copay); that patient subsequently experienced an increase in hallucinations while on clozapine and then returned to his baseline levels of psychosis when clozapine was discontinued and pimavanserin was reinitiated [26]. In addition, 4 retrospective medical record reviews, 1 case report, and 1 clinical trial included patients with DLB alongside other larger cohorts, but these publications did not report clear histories or specific findings on the patients with DLB.

The findings from these past publications seem to generally align with our observations. As part of a series of retrospective chart reviews that included patients with various kinds of dementia, investigators at a movement disorders clinic in Providence, Rhode Island, reported on 15 patients with DLB who experienced psychosis. Although the reviews share few details about the specific cases with DLB or the long-term resolution of their symptoms, it appears that 10 of the 15 patients experienced at least mild or temporary improvement of psychosis when receiving pimavanserin [27–29] Likewise, Mahajan et al performed a retrospective chart review that included 1 patient with DLB and psychosis who reported more benign hallucinations following monotherapy with pimavanserin [30]. Most significantly, a phase-3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled discontinuation trial that enrolled patients with various forms of dementia found that participants who continued receiving pimavanserin were less likely to relapse into psychosis than patients who discontinued pimavanserin. That study included 38 participants with DLB but did not provide DLB-specific findings and was stopped early due to findings of efficacy; thus, larger studies that encompass a longer trial period and include DLB-specific findings are necessary [31].

Our case report therefore adds important context regarding the application of pimavanserin in patients with DLB. As Hershey et al point out, pimavanserin may fill the gap for patients with DLB psychotic symptoms that do not respond to cholinesterase inhibitors, which are contraindicated in patients with arrhythmias, but caution is needed as pimavanserin may be associated with an increased risk of death for elderly patients [14]. Burstein has countered that pimavanserin has been well tolerated in multiple studies featuring elderly fragile patients [32], and that was our experience in this case series, as pimavanserin appeared tolerable for each of our patients and resulted in long-lasting positive effects for 3 of our 4 patients.

Finally, it is unclear why pimavanserin improved psychosis in Patients 1, 2, and 4 but not Patient 3. In a retrospective cohort study comparing pimavanserin and quetiapine in patients with PD and DLB (without differentiation between the 2 patient groups), Horn et al found that pimavanserin may be more useful than quetiapine for promptly addressing psychosis, and they also note that 5 of the 8 patients who discontinued pimavanserin also took quetiapine concurrently at some point in their care [33]. As we have shown, multiple patients in our case series received quetiapine at some point in their care; however, only the patient who eventually discontinued pimavanserin received pimavanserin and quetiapine concurrently. Although this may suggest that the combination of drugs led to the lack of efficacy for pimavanserin in this patient, additional research is necessary to investigate this point.

Conclusions

Given that this is a small case series and not a clinical trial, we cannot definitively remark upon the value of pimavanserin for patients with DLB and psychosis. Nevertheless, this case series is useful in that it includes 4 patients with DLB who presented with a variety of clinical histories, including, for instance, patients with a neuroleptic malignant syndrome or PTSD. The case series also combines the insights of 2 experienced geriatric psychiatrists who directly interacted with the patients and their caretakers. That work shows that for some patients with DLB who experience treatment-resistant psychosis, the new second-generation atypical antipsychotic pimavanserin may reduce distressful hallucinations and delusions while avoiding the side effects of other second-generation antipsychotics. Additional clinical trial data in patients with DLB and psychosis would be useful, but in the meantime, our case series suggests that the clinical trial findings observed in other dementia populations may be relevant for patients with DLB and that the risk-versus-benefit ratio for pimavanserin appears likely to be favorable in many patients who suffer from psychosis in this debilitating disorder.

References:

1.. Galvin JE, Balasubramaniam M, Lewy body dementia: The under-recognized but common: FOE Cerebrum, 2013; 2013; 13

2.. Vann Jones SA, O’Brien JT, The prevalence and incidence of dementia with Lewy bodies: A systematic review of population and clinical studies: Psychol Med, 2014; 44(4); 673-83

3.. Walker Z, Possin KL, Boeve BF, Aarsland D, Lewy body dementias: Lancet, 2015; 386(10004); 1683-97

4.. McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium: Neurology, 2017; 89(1); 88-100

5.. Emre M, Tsolaki M, Bonuccelli U, A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial: Lancet Neurol, 2010; 9(10); 969-77

6.. Edwards K, Royall D, Hershey L, Efficacy and safety of galantamine in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies: A 24-week open-label study: Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 2007; 23(6); 401-5

7.. Satoh M, Ishikawa H, Meguro K, Improved visual hallucination by donepezil andoccipital glucose metabolism in dementia with Lewy bodies: The Osaki-Tajiri project: Eur Neurol, 2010; 64(6); 337-44

8.. Kyle K, Bronstein JM, Treatment of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy Bodies: A review: Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 2020; 75; 55-62

9.. Cummings JL, Devanand DP, Stahl SM, Dementia-related psychosis and the potential role for pimavanserin: CNS Spectr, 2022; 27(1); 7-15

10.. Kurlan R, Cummings J, Raman R, Quetiapine for agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia and parkinsonism: Neurology, 2007; 68(17); 1356-63

11.. Takahashi H, Yoshida K, Sugita T, Quetiapine treatment of psychotic symptoms and aggressive behavior in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies: A case series: Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2003; 27(3); 549-53

12.. Marsh L, Williams JR, Rocco M, Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with Parkinson disease and psychosis: Neurology, 2004; 63(2); 293-300

13.. Pollak P, Tison F, Rascol O, A randomised, placebo controlled study with open follow up: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2004; 75(5); 689-95

14.. Hershey LA, Coleman-Jackson R, Pharmacological management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Drugs Aging, 2019; 36(4); 309-19

15.. Ballard C, Banister C, Khan Z, Evaluation of the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of pimavanserin versus placebo in patients with Alzheimer’s disease psychosis: A phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study: Lancet Neurol, 2018; 17(3); 213-22

16.. Ballard C, Youakim JM, Coate B, Stankovic S, Efficacy in patients with more pronounced psychotic symptoms: J Prev Alzheimers Dis, 2019; 6(1); 27-33

17.. Cummings J, Isaacson S, Mills R, A randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial: Lancet, 2014; 383(9916); 533-40

18.. Cummings J, Ballard C, Tariot P, Potential treatment for dementia-related psychosis: J Prev Alzheimers Dis, 2018; 5(4); 253-58

19.. Weintraub D, Hurtig HI, Presentation and management of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: Am J Psychiatry, 2007; 164(10); 1491-98

20.. Scheepmaker AJ, Horstink MW, Hoefnagels WH, Strijks FE, [Dementia with Lewy bodies; 2 patients with exacerbation due to an atypical antipsychotic, but with a favorable response to the cholinesterase inhibitor rivastig-mine.]: Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd, 2003; 147(1); 32-35 [in Dutch]

21.. Bonelli SB, Ransmayr G, Steffelbauer M, L-dopa responsiveness in dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson disease with and without dementia: Neurology, 2004; 63(2); 376-78

22.. Rothenberg K, Wiechers I, Antipsychotics for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia – safety and efficacy in the context of informed consent: Psychiatr Ann, 2015; 45(7); 348-53

23.. Culo S, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, A randomized controlled-trial: Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 2010; 24(4); 360-64

24.. Cummings J, Ritter A, Rothenberg K, Advances in management of neuro-psychiatric syndromes in neurodegenerative diseases: Curr Psychiatry Rep, 2019; 21(8); 79

25.. Rothenberg K, Assessment and management of psychiatric symptoms in neurodegenerative disorders: Neuro-Geriatrics: A Clinical Manual, 2017, Switzerland, Springer International

26.. Abadir A, Dalton R, Zheng W, Neuroleptic sensitivity in dementia with Lewy body and use of pimavanserin in an inpatient setting: A case report: Am J Case Rep, 2022; 23; e937397

27.. Friedman JH, A retrospective study of pimavanserin use in a movement disorders clinic: Clin Neuropharmacol, 2017; 40(4); 157-59

28.. Friedman JH, Pimavanserin for psychotic symptoms in people with parkinsonism: A second chart review: Clin Neuropharmacol, 2018; 41(5); 156-59

29.. Akbar U, Friedman JH, Long-term outcomes with pimavanserin for psychosis in clinical practice: Clin Park Relat Disord, 2022; 6; 100143

30.. Mahajan A, Bulica B, Ahmad A, A single-center experience: Neurol Sci, 2018; 39(10); 1767-71

31.. Tariot PN, Cummings JL, Soto-Martin ME, Trial of pimavanserin in dementia-related psychosis: N Engl J Med, 2021; 385(4); 309-19

32.. Burstein ES, Relevance of 5-HT(2A) receptor modulation of pyramidal cell excitability for dementia-related psychosis Implications for pharmacotherapy: CNS Drugs, 2021; 35(7); 727-41

33.. Horn S, Richardson H, Xie SX, Pimavanserin versus quetiapine for the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 2019; 69; 119-24

In Press

19 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943136

21 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943645

21 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.942921

22 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943346

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250