05 December 2023: Articles

A Rare Skin Rash: Linezolid-Induced Purpuric Drug Eruption without Vasculitis in a Hispanic Male

Challenging differential diagnosis, Adverse events of drug therapy

Marilee A. Tirú-Vega1ABCDEF*, Natalie Engel-Rodriguez2BDE, Nicole Rivera-Bobé3BCDEF, Carla N. Cruz-DíazDOI: 10.12659/AJCR.941725

Am J Case Rep 2023; 24:e941725

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Cutaneous adverse drug reactions are the skin’s response to a systemic exposure to drugs. Linezolid is an oral oxazolidine used to treat methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Even though it has well-known adverse effects, purpuric cutaneous adverse drug reactions to linezolid have been scarcely described. This report is of a Puerto Rican man in his 80s who developed an extensive purpuric drug eruption secondary to linezolid use. Clinicians should be aware of this phenomenon, since prompt identification and discontinuation of the agent are essential for recovery.

CASE REPORT: An 89-year-old Puerto Rican man was given oral linezolid therapy for healthcare-associated pneumonia and developed a widespread, purpuric cutaneous eruption 5 days into therapy. His condition prompted immediate discontinuation of the drug. Forty-eight hours after stopping the medication, he visited the Emergency Department. Abdominal punch biopsy revealed a superficial and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with dermal eosinophils, a pathologic finding consistent with a purpuric drug eruption. This allowed for a timely diagnosis, exclusion of other mimickers, such as cutaneous vasculitis, and effective management.

CONCLUSIONS: Cutaneous adverse drug reactions to linezolid have been scarcely reported in the literature. Due to the low incidence of this manifestation, the identification of the causative agent and accompanying treatment may be delayed. Mainstays in therapy are avoidance of the offending agent and treatment with corticosteroids, antihistamines, barrier ointments, and oral analgesics. Primary healthcare providers should be aware of linezolid-induced cutaneous manifestations, diagnostic clues, and treatment options so they can rapidly identify and effectively treat such complications.

Keywords: Drug Eruptions, linezolid, Purpura, Vasculitis

Background

Linezolid is an oxazolidinone indicated for gram-positive infections and approved for the treatment of bacterial pneumonia, skin and skin structure infections, and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus infections, including infections complicated by bacteremia [1]. It is particularly useful for the treatment of methicillin-resistant

We herein present the case of an 89-year-old Puerto Rican man who developed an extensive purpuric drug eruption secondary to linezolid use with consistent pathologic findings. To date, only a single case of this reaction has been previously reported [4].

Case Report

An 89-year-old Hispanic male patient with medical history of chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3a, hypertension, and asthma was admitted to the hospital after presenting with whole-body rash and generalized pruritus that began 5 days after receiving oral linezolid 600 mg every 12 hours for healthcare-associated pneumonia. His condition prompted the immediate discontinuation of the drug. However, 48 hours after stopping the medication, the rash continued progressing, so he decided to visit the Emergency Department. Upon further questioning, the patient stated that the rash began as a papule on his right elbow resembling an insect bite, which then evolved into diffuse purpuric and erythematous lesions that spread quickly to the contralateral upper extremity, bilateral lower extremities, abdomen, palms, and soles. It spared the face, chest, back and mucosa. He described the rash as pruritic. He denied difficulty swallowing, tongue swelling, mucosal lesions, fever, chills, weight loss, myalgias, arthralgias, gastrointestinal symptoms, bloody urine, or bloody stools. He denied any history of allergic reactions to medications, any other new medications, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, or recent changes in nutrition. No one in the household had a similar rash. He denied sick contacts, recent outdoor activities, or recent travel.

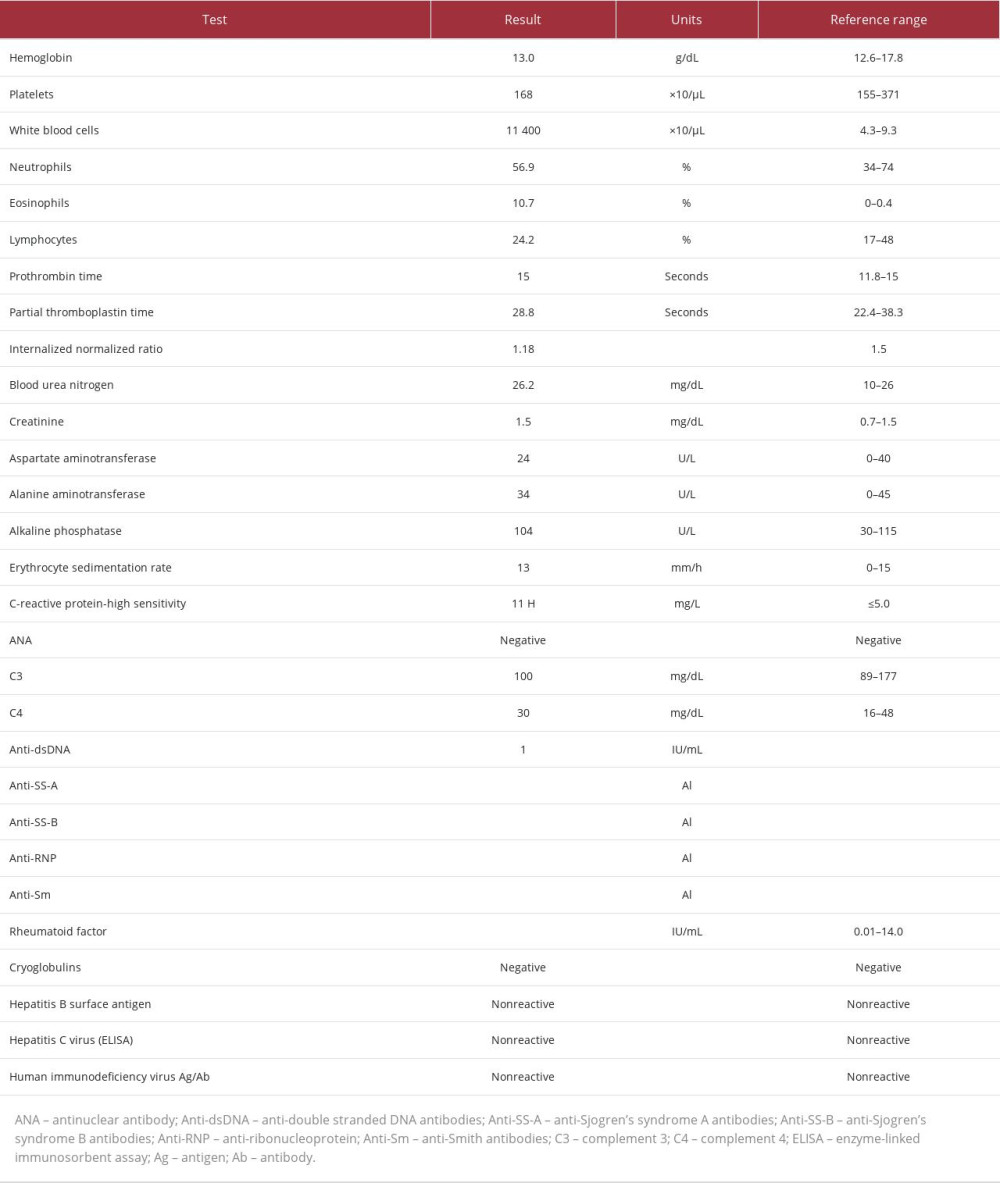

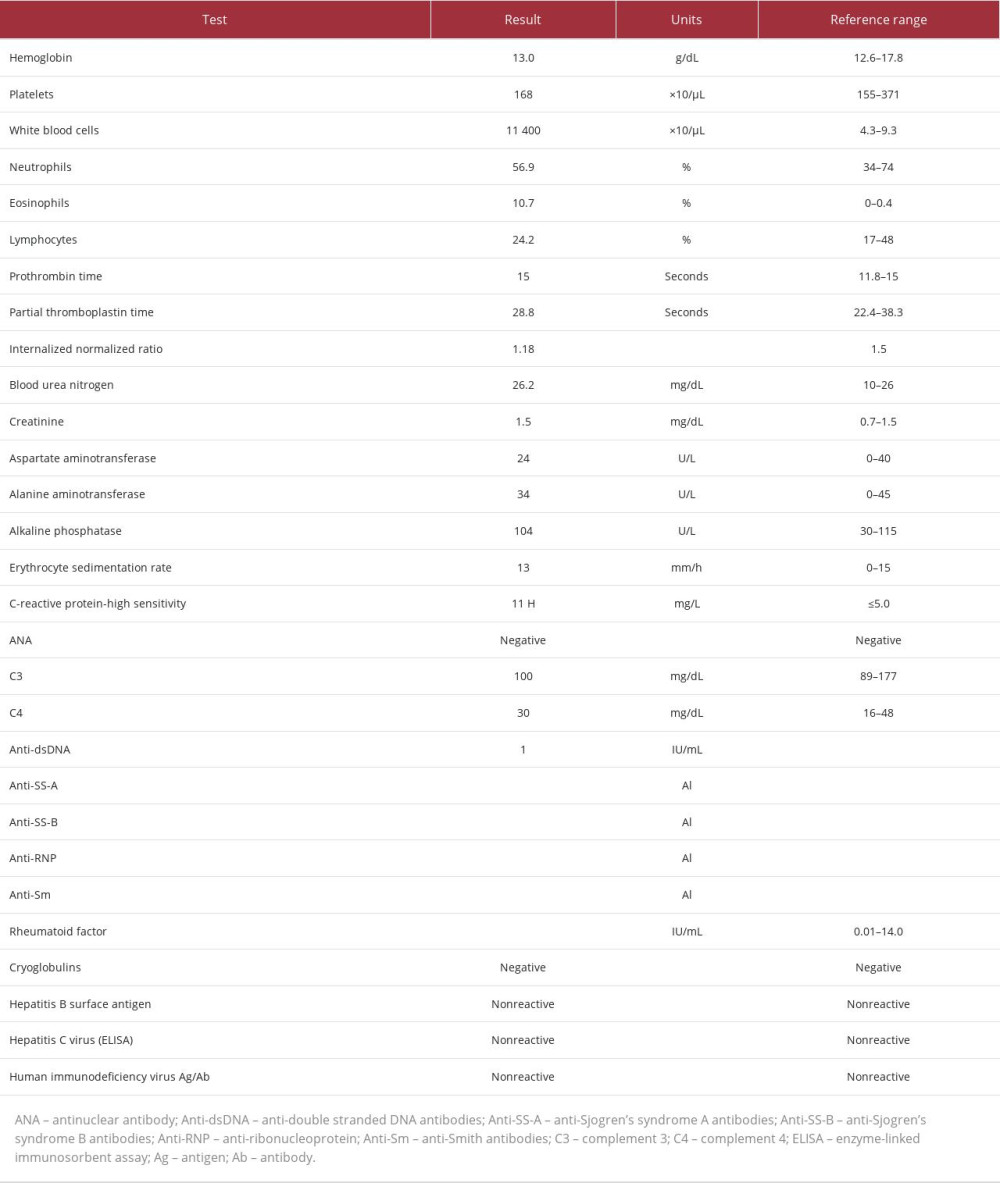

On further evaluation, he was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Clinical examination revealed disseminated, warm and nonblanchable, purpuric macules and patches over the bilateral upper extremities, abdomen, inguinal area, and bilateral lower extremities (Figure 1). The palms and soles, as well as the dorsum of the hands and feet were involved. The rash spared the scalp, face, upper chest, and back. There was no lymphadenopathy, mucosal involvement, or skin sloughing. Laboratory values (Table 1) showed leukocytosis with marked eosinophilia, and no bandemia or left-shifting. Hemoglobin and platelet counts were within normal limits and as per patient’s baseline. No coagulopathies were seen. Chemistry revealed no electrolyte disturbances and renal function was within his baseline, congruent with known CKD. His liver enzymes were unremarkable. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal and C-reactive protein was elevated. Final bacterial and urine cultures revealed no growth. As shown in Table 1, the auto-immune and vasculitis workup performed was also unremarkable.

The dermatology service evaluated the patient that same day and performed a punch biopsy from a lesion located on his abdomen that appeared to be well-developed and 24–48 hours old. The biopsy was taken including a small peripheral rim of normal skin so that the dermatopathologist could observe the transition from normal to diseased skin. A separate biopsy for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) was not taken in our case, as there were no lesions <24 hours old. The timing of when the biopsies are taken is crucial in establishing a diagnosis of leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a fresh lesion, within 24–48 hours of onset, is best for histopathological assessment, while a newer lesion, within 8–24 hours of onset, is best for DIF [5,6]. Histopathology in our case revealed a superficial and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with dermal eosinophils (Figure 2). The patient was started on methylprednisolone 80 mg intravenously every 8 hours, betamethasone dipropionate cream twice a day, pramoxine 1% lotion as needed for pruritus, and oral cetirizine 10 mg daily. The patient’s skin and symptoms drastically improved following 1 week of therapy. The dermatology service concluded, based on the patient’s clinical presentation of purpuric macules and patches that started 5 days after commencing linezolid, in addition to the previously described laboratory and pathology findings, that the most likely diagnosis was a purpuric drug eruption secondary to linezolid.

Discussion

Linezolid can be the causative agent of cutaneous adverse drug reactions, including purpuric drug eruptions – a usually pruritic, non-blanchable skin rash without vasculitis. An undesirable manifestation of the skin resulting from the administration of a drug is the definition of a cutaneous adverse drug reaction (CADR). While the medication package insert for line-zolid reports an incidence for CADRs of 2%, some authors have reported a higher rate of 4% [7]. Furthermore, in a series of 44 patients, 2% had a CADR severe enough to require discontinuation of the linezolid [8]. A CADR with linezolid is thus rare, with most common reactions being from IgE hypersensitivity such as angioedema, urticaria, and flushing [3]. According to the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability scale, which is a questionnaire that assesses the relationship between a clinical event and exposure to a drug [9], the patient’s score was 6/10, indicative of a probable drug reaction.

Among the differential diagnoses in this case, maculopapular drug eruption, drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), and leukocytoclastic vasculitis were considered. DRESS is characterized by a triad of fever, rash, and internal organ damage. The clinical sequence usually commences with high-grade fever (38–40°C) followed by a maculopapular rash that includes the face, upper extremities, and upper trunk, and tender lymphadenopathy; none of which were present in our patient. In addition, this patient’s rash occurred 5 days after starting linezolid, which is a shorter interval than the average 21 days typically reported for DRESS [10]. A maculopapular drug eruption, also called morbilliform or exanthematous due to its similarity in morphology to measles, is the most commonly seen type of CADR. Clinical presentation usually involves pink to erythematous macules and/or papules that begin on the trunk and spread symmetrically to the extremities [11]. Our patient had purpuric lesions instead; therefore, drug-induced cutaneous vasculitis was also considered.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is a type of small-vessel cutaneous vasculitis characterized by palpable purpura, that usually starts in dependent areas of the body such as the lower extremities. Studies suggest that it is a type 3 hypersensitivity reaction with immune complex deposition in the vessels of the dermal capillaries and venules [12]. Common triggers include infectious processes, drugs, systemic autoimmune diseases, or malignancies [5]. Skin biopsy is the standard for diagnosis [5]. Characteristic histopathology shows endothelial cell swelling, fibrinoid necrosis, blood vessel degeneration, and neutrophilic infiltrate and debris (leukocytoclasia) [6]. In 2005, Saez et al described the first case of histopathology-confirmed leukocytoclastic vasculitis secondary to linezolid use [13]. Kruzer et al further described a biopsy-confirmed, linezolid-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis which presented as a purpuric rash 6 days after starting oral linezolid therapy for methicillin-resistant

Even though our patient did have purpuric lesions in the lower extremities, he did not present any non-blanching purpuric papules (palpable purpurae), vesicles, or necrosis as can be seen clinically with leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Due to the previously described skin eruption and a histopathology of a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with eosinophilic predominance, the diagnosis of purpuric drug reaction secondary to linezolid use was made. To our knowledge, this would be the second report of a non-blanching purpuric drug eruption to linezolid as previously described by Kim et al [4]. Rapid identification of the predisposing agent causing the drug eruption and its discontinuation due to the patient’s symptoms, followed by immediate treatment, led to a successful, full recovery in our patient.

Conclusions

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions to linezolid have been scarcely reported in the available literature. Due to the low incidence of this manifestation, the identification of the causative agent and accompanying treatment may be delayed. Further, there are no concrete guidelines on how to treat this complication. Mainstays in therapy are avoidance of the offending agent and treatment with corticosteroids, antihistamines, barrier ointments, and oral analgesics. Primary healthcare providers should be aware of linezolid-induced cutaneous manifestations, diagnostic clues, and treatment options so they can rapidly identify and effectively treat such complications.

Figures

References:

1.. Azzouz A, Preuss CV, Linezolid. [Updated 2023 Mar 24]: StatPearls [Internet], 2023, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539793/

2.. French G, Safety and tolerability of linezolid: J Antimicrob Chemother, 2003; 51(Suppl. 2); ii45-53

3.. Dilley M, Geng B, Immediate and delayed hypersensitivity reactions to antibiotics: Aminoglycosides, clindamycin, linezolid, and metronidazole: Clin Rev Allergy Immunol, 2022; 62(3); 463-75

4.. Kim FS, Kelley W, Resh B, Goldenberg G, Linezolid-induced purpuric medication reaction: J Cutan Pathol, 2009; 36(7); 793-95

5.. Baigrie D, Goyal A, Crane JS, Leukocytoclastic vasculitis. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]: StatPearls [Internet], 2023, Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482159/

6.. Morita TCAB, Criado PR, Criado RFJ, Update on vasculitis: Overview and relevant dermatological aspects for the clinical and histopathological diagnosis – Part II: An Bras Dermatol, 2020; 95(4); 493-507

7.. Birmingham MC, Rayner CR, Meagher AK, Linezolid for the treatment of multidrug-resistant, gram-positive infections: Experience from a compassionate-use program: Clin Infect Dis, 2003; 36(2); 159-68

8.. Bishop E, Melvani S, Howden BP, Good clinical outcomes but high rates of adverse reactions during linezolid therapy for serious infections: A proposed protocol for monitoring therapy in complex patients: Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2006; 50(4); 1599-602

9.. Copaescu AM, Trublano JA, The assessment of severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions: Aust Prescr, 2022; 45(2); 43-48

10.. Savard S, Desmeules S, Riopel J, Agharazii M, Linezolid-associated acute interstitial nephritis and drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome: Am J Kidney Dis, 2009; 54(6); e17-e20

11.. Ernst M, Giubellino A, Histopathologic features of maculopapular drug eruption: Dermatopathology (Basel), 2022; 9(2); 111-21

12.. Kruzer K, Garner W, Honda K, Packer CD, Linezolid-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis: Ann Pharmacother, 2018; 52(12); 1263-64

13.. Sáez de la Fuente J, Escobar Rodríguez I, Perpiñá Zarco C, Bartolomé Colussi M, [Linezolid-related leukocytoclastic vasculitis.]: Med Clin (Barc), 2005; 124(16); 639 [in Spanish]

Figures

Tables

Table 1.. Pertinent laboratory values of an 89-year-old male patient presenting with a drug-induced purpuric cutaneous eruption secondary to linezolid use. The table includes blood count, metabolic panel, and autoimmune, vasculitis, and infectious work-ups.

Table 1.. Pertinent laboratory values of an 89-year-old male patient presenting with a drug-induced purpuric cutaneous eruption secondary to linezolid use. The table includes blood count, metabolic panel, and autoimmune, vasculitis, and infectious work-ups. Table 1.. Pertinent laboratory values of an 89-year-old male patient presenting with a drug-induced purpuric cutaneous eruption secondary to linezolid use. The table includes blood count, metabolic panel, and autoimmune, vasculitis, and infectious work-ups.

Table 1.. Pertinent laboratory values of an 89-year-old male patient presenting with a drug-induced purpuric cutaneous eruption secondary to linezolid use. The table includes blood count, metabolic panel, and autoimmune, vasculitis, and infectious work-ups. In Press

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943070

17 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943370

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943803

18 Mar 2024 : Case report

Am J Case Rep In Press; DOI: 10.12659/AJCR.943467

Most Viewed Current Articles

07 Mar 2024 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.943133

Am J Case Rep 2024; 25:e943133

10 Jan 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935263

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935263

19 Jul 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.936128

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e936128

23 Feb 2022 : Case report

DOI :10.12659/AJCR.935250

Am J Case Rep 2022; 23:e935250